I felt like I had been raised by this industry,” Sarah Meier tells me over Skype, of the profession she entered in her mother’s footsteps at 14. The former supermodel now lives in Manila and has no regrets about leaving the world that brought her up. It does sound tough. “Really, really, really nice girls turned into horrible creatures,” she says.

She isn’t referring to some cutthroat reality show, although she was set to front Philippines’ Next Top Model before the show was canceled in 2013. She’s referring to her 12 years in the display sector of a fashion industry that employs more than a seventh of all the women on the planet.

Any teen alone in New York City would struggle, but Meier’s calm presence, clear head and stunning beauty saw her through. She attended up to ten castings per day, each filled with critics offering professional and often conflicting opinions about her physical flaws. After a few years, she began to feel a creeping sense of self-doubt. She wasn’t the only one being changed by the job.

The erstwhile “nice girls” primarily refer to her endless string of roommates. The modeling agencies also arrange for housing—but the expenses come out of employee paychecks, not unlike housing for overworked, underpaid Southeast Asian garment factory workers, which is often owned by a nearby factory. Move-in was always great, Meier recalls. But “three months down the road, they’re putting Nair in each other’s shampoo bottles.”

The travails of models don’t necessarily arise out of professional rivalry. “You could be looking at a blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl, and you’re not in competition with her at all,” says Meier, who has light brown skin, dark brown hair and bright green eyes. As a woman of color among white folks, she explains, “we’re not going to be up for the same jobs, ever.”

Still, she says, “the animosity begins to build,” and not just “for other models. Animosity for anybody that’s happy. Anybody that’s living a normal life.”

Class warriors will recognize Meier’s testimony as a textbook description of proletarian alienation, although few are inclined to think of models as workers. To judge by their portfolios and Instagram feeds, models spend their time at swanky cocktail soirees, on Caribbean beaches, or weaving down urban ways, laughing with their heels in their hands. Yet even models like Meier, hovering near the top of the modeling food chain, can find this stylized mimicry of the good life an intolerable, degrading grind. Add in the vicious campaigns of interpersonal one-upmanship as virtual conditions of employment, and a spectator may look beyond these images to ponder the self that is being assembled as an object of choice for ornamentation.

In other words, the toxicity inherent to the modeling caste is a feature of the fashion industry, not a bug: no minor flaw in an otherwise efficient system, but a condition of the job. Off-camera, the health and wellbeing of models is a labor issue.

The charge that models have a rough go of it has never been terribly well-received by labor activists or feminists. After all, the posh surface of the industry gleams with self-indulgence, and a suspicion can arise that most models haven’t spent enough time in the real world to glean that unjust treatment may not be heaped upon them because of their job, but because of their gender. Even the breed of feminist politically awakened by Beyoncé’s VMA performance can tick off the profession’s glaring ideological sins: its misogynist conflation of Woman with salable object; its role in lionizing impossible beauty standards; and its casual enactment of reflexive female consent in the realm of sexual power—the complex of predatory prerogatives we’ve come to call rape culture. Fighting for fair wages or adequate child labor protections in an industry steeped in—if not foundational to—the iconography of male privilege can seem like petitioning the Koch brothers to join Code Pink.

After all, modeling is, by any reasonable measure, a decidedly elite career. Even insiders pointing out unfair labor practices describe an “exclusive…hyper-wealthy country club-like industry” and complain that agencies take too high a percentage of presumably lavish salaries. Meier characterizes her taste of the lush life in positive terms: “I know what a really expensive car feels like to sit in. I know what it smells like,” she tells me. “I’ve tasted some really incredible food and seen some really beautiful places in the world.”

Yet country clubs and expensive cars come staffed, a nuance Meier seems to have noted but others may overlook. One former cover girl, calling on actors’ union SAG-AFTRA to grant models entry, recalls in Guernica of life in a model apartment where “we didn’t pick up after ourselves or clean the floor.” It’s hard to work up much in the way of labor solidarity for folks who seemingly don’t bother to, you know, labor.

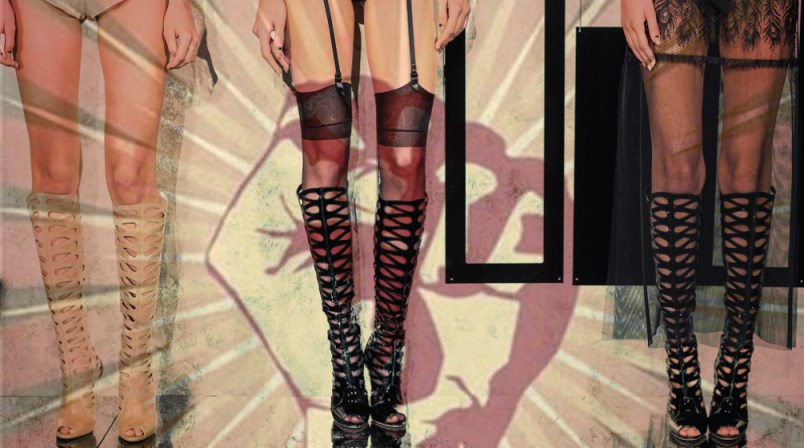

Even as the rallying cry for models to unionize has gained volume around the world, solidarity with other labor sectors has lagged. What models do is sell, not construct or argue or plan, and any effort to stir them into action inevitably ends up navigating the narrow catwalk between cause marketing and genuine labor organizing. Visit the website for the advocacy group Model Alliance, for example, which stops short of actually organizing workers, and a pop-up ad for a calendar will temporarily block you from reading a draft of the Models’ Bill of Rights. The calendar “features twelve models who the Alliance feels represent female empowerment and diversity in the American modeling industry,” according to the site. Sure enough, the sexualized pouts of twelve women smizing through a variety of skin tones adorn each month of the year. The draft bill of rights, on the other hand, proposes concrete measures to end wage theft, ensure fiscal oversight of agencies, and minimize child labor—noticably unsexy fare when set against the calendar’s array of seductive poses. The master’s tools may not dismantle the master’s house, but check out how great they look in action!

The cognitive dissonance of the Model Alliance website hints at the limited effectiveness of the group itself: It collects information helpful to models who wish to see their experiences reflected in hard data or take the next logical step: a push for unionization. But as it stands, the group is too invested in the industry to enter the collective bargaining game themselves.

“Founding a union makes a strong oppositional statement that scares off people,” director of the Fashion Law Institute Susan Scafidi explained to the New York Times in a piece about Model Alliance in 2013.

Yet peer beyond the playful pouts and admonitions for models to make nice, and you come to realize that a union for fashion models makes sense. The struggles facing the women paid to act out patriarchal notions of beauty, glamour and worldliness, in fact, are not so different from those we hear from any other woman involved in the global garment trade, at any phase of production or distribution, all of which have, or are working toward, unionization.

It’s a brutal world,” Meier tells me. “They do want you to come in at the age of 13, 14, hoping that you’ll hit your prime at 17.”

Indeed, a 2012 Model Alliance report found that more than half the models surveyed had started between 13 and 16; another 1 percent had started earlier. (The Model Alliance sample size was small—85 completed surveys, from the 241 who received it—but so is the modeling world. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS, tallied 4800 working models that same year.) I tell Meier that my only experience being surrounded by a workforce so young was reporting from the garment factories in Cambodia, and Meier nods without surprise.

Labor and human rights violations on the production end of global fashion are easy to recognize, particularly when they take place elsewhere. Garment worker uprisings, with hundreds of thousands of women walking off factory floors demanding higher wages, have streamed from across Asia in recent years. But a close look at the display sector reveals a distressing litany of similarities with apparel laborers that only begins with the underage workforce.

Long, irregular hours are another common concern. Like garment factory employees, often required to work mandatory overtime, models report working 14 to 20 hour days without advance notice, a practice so consistent it shows up in the BLS job description. Lack of scheduling predictability was also a complaint of warehouse workers I spoke to in Joliet, Illinois, where the managers had a habit of locking workers into buildings during shifts, supposedly to minimize theft. In Cambodia, childcare options are few and expensive, so workers must delay having children, ship kids back home to grandparents or invest in a good deadbolt and hope for the best, as one worker I visited did.

For all fashion workers, the pressure to remain malnourished is high (although this genuine health concern is often written off as a self-directed “desire to remain thin” in Western circles). Malnutrition remains a top concern throughout the fashion industry—it plays a major role in Cambodia’s mass faintings of garment workers, for example—and the lengths to which models go to keep slender is well-documented. Thirty-one percent admit to eating disorders in the Model Alliance survey. One supermodel was advised to eat only a rice cake a day, while others are offered subtle hints, often backed up by contract stipulations, to lose inches. Related health hazards are also present; 68 percent of the workforce suffers from anxiety and/or depression, noted the same survey. A quarter profess drug or alcohol dependency, and around a third said they lacked health insurance (although the survey took place in 2012, before the Affordable Care Act was implemented).

Jennifer Sky, former Maxim and Sassy cover model-turned-Xena: Warrior Princess regular, says the industry gave her PTSD. Now she’s a writer and sits on the advisory board of Model Alliance. (Sarah Ziff, the founder of Model Alliance, did not respond to interview requests.) In an emotional YouTube video, Sky describes unsupervised foreign travel as a child and a lengthy shoot in a swimming pool, when her legs turned an unattractive shade of blue. She was scolded for it, and years of such criticism began to wear on her, just as it did Meier. Sky’s emotional health tanked.

“The caste system on a set is specific and hard to navigate,” she writes in an email. “And, while the model is the focal point, he/she is most often (unless a supermodel), at the bottom of the social caste.” Makeup artists, hairstylists, clothing stylists, the photographer and the brand manager are all there to dictate a model’s every move. “Their body is a commodity for other people,” Sky explains.

Emotional neglect, meager sustenance and unpredictable hours would create rough conditions for any worker under the age of 18, but the industry is also a big-money honeytrap for male predators. Its poster boy is “Uncle” Terry Richardson, one of the highest-paid photographers in the world. He has been regularly named in sexual assault and harassment complaints since 2005, for on-shoot behavior that includes non-consensual jizzing, offers to make tea from used tampons and demands that models squeeze his balls. (No surprise that Bill Cosby, too, evinced a strong preference for models.)

“This is an industry that obviously lends itself to sexual harassment at the workplace,” Sky says. More true than she realizes: The production side of the fashion industry is notoriously fraught with harassment complaints. A 2006 Better Factories Cambodia study found that around 30 percent of the garment factory workforce—95 percent women, at the time—experienced sexual harassment on the job. A more recent 2012 report from the ILO found that that number had dropped to 20 percent, a decline almost certainly stemming from the increase in male employees during the industry’s post-recession expansion in the country.

Retail thrift store employees and warehouse workers are also targets of verbal or physical aggression and unwanted sexual advances. One worker in the Joliet warehouse I visited in 2012, where clothes are shipped to WalMart and fast-fashion chains, told me she was raped by her manager, fired when she filed a complaint and only reinstated after several coworkers joined protests in solidarity. Other workers say sexual harassment at warehouses is high because of the relatively few female employees and extensive surveillance equipment common in the Foreign Trade Zones where warehouses are situated. Even in supposedly sustainable secondhand fashion, the industry sexualizes female laborers: Complaints have been filed against Apogee Retail Inc., owners of the for-profit Unique Thrift Store chain, for sexual harassment and abuse.

Meanwhile, Model Alliance found that 30 percent of models experience inappropriate, on-the-job touching, 28 percent feel pressured to have sex with someone at work and 61 percent express concern over their lack of privacy while changing clothes. Only 29 percent feel they can report sexual harassment to their agency, although two thirds of them found that, once reported, the agency didn’t respond. Eighty-seven percent have been asked to pose nude without advance notification.

Think about it: A largely under-18 workforce consistently asked to strip for cameras without supervision isn’t just commonplace—it’s also legal. Agencies are able to recruit heavily from the preteen set thanks to a loophole carved out in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 known as the Shirley Temple Act, which requires individual states to pass their own laws protecting child performers or farm workers. New York is one of many states that have passed such protections—although 18 others have not—and in late 2013, Model Alliance successfully petitioned New York to reclassify print and runway models under the age of 18 as child performers, a protection that demands permits for minors, sets maximum hours, assures breaks and offers educational requirements and chaperones for those under 16. Compliance has been slow, but some in the industry say they’ve seen a slight upward trend in models’ ages since. It’s a tiny sliver of hope considering the string of abuses reported by fashion workers globally. But it’s something.

We tend to conflate the glamorous image models project with the amount they are paid to project it. We imagine them recovering from hangovers still draped in beaded couture, a leg flung casually over the back of a designer leather couch while a voice-controlled smoothie-maker purrs in the modern, high-end kitchen beyond. But anyone who’s ever failed to pull off a dress they first glimpsed in a full-page ad knows the fashion industry doesn’t live up to its own claims. Models—surprise!—seldom live lavish lifestyles. In fact, they earn significantly less than we imagine, and certainly less than one might expect in exchange for putting up with systemic labor abuses.

BLS suggests models in the U.S. earned on average only around $19,300 in 2013, which breaks down to a mean hourly wage of $9.28 per hour. (Compare to the male-dominated fields of fashion photography, where workers earn a mean of $37,190, and fashion design, whose workers took in around $78,410 that year.) Retail sales workers across all industries earn mean annual incomes of $21,890, and big clothing retail chains claim 85-95 percent female workforces. Warehousing and storage workers, who tend to be male, earned an annual mean in 2013 of $29,630.

But look more closely at those earnings. The $9.28 per hour models earned represents just 83 percent of the $11.50 per hour living wage in New York for 2013. It’s a higher percentage of the living wage than factory workers take home in Mexico (67 percent), Guatemala (50 percent), Vietnam (29 percent), or Bangladesh (14 percent), and part of a model’s living wage may be offset by the country-club lifestyle and low food budget. Yet the fact remains that the pay for a field dominated by women is always a percentage of a living wage, and never intended to ensure survival.

Pay is therefore low in the fashion industry across the board, when it comes at all. Workers in Haitian and Indian garment factories last year filed complaints that they were receiving less than minimum wage, and workers at retail-outlet stockhouses also face wage theft. Laborers at a Walmart supplier in California won a lawsuit last March for $21 million in backpay, and workers at a Forever 21 warehouse filed a similar claim in 2013, stating that no compensation for overtime had been paid and no meal or rest breaks offered. Models have likewise reported wage retention from agencies for such egregious offenses as having gained too much weight, and delays of months, even years, in receiving checks. Agencies charge for tests, visas, portfolios and delivery fees—all deducted from earnings before payout and not always tallied for workers’ financial records. Additionally, some designers “pay” in “trade”—apparel that is often too small to sell to anyone else and not hardy enough for everyday wear.

“Stuff does not put food on the table or a roof over one’s head,” Sky says. “It is the extreme arrogance of the fashion industry that someone like Marc Jacobs, who runs a massive global corporation, would not pay twenty young women five hundred dollars each to walk in his show instead of ‘gifting’ them a garment or two.”

Despite the steady advocacy of women like Sky, models face massive barriers to ensuring protective measures. Agencies guard against costly legal action by claiming that models are independent contractors, not employees. The temp agencies where warehouses contract for labor do the same. This designation leaves fashion workers uncovered by many of the sexual harassment protections that apply to other classes of employees. It also makes organizing difficult—and dovetails neatly with fashion’s individuality-forward ethos.

Arguments to eradicate these entrenched traditions are self-evident. Model Alliance offers some tools to put helpful regulations in place, but remains embedded in an industry that requires substantial change. Still, models’ unions seem more and more likely. Sky puts it bluntly: “To offer no protections is absurd.”

Resting on the shaky foundation we dismiss as “beauty standards,” the modeling industry contains far more distressing implications for a democracy than mere aesthetic preference would indicate. For models are not only selected to reflect (read: entrench) cultural norms, as would state their stripped-down job description, they are required to invent them anew. The modeling industry, in turn, strives to offer that unique combination of recognizably desirable and wholly inoffensive. Generally unchallenging, in other words, to white, mainstream, heteronormative ‘Merica.

Racial discrimination is therefore bedrock. Consider Meier, a woman of color, who excuses the animosity she felt from white models because she wasn’t competing with them for jobs. As a Filipino-Swiss woman, she simply couldn’t have, within the confines of an industry founded on physical discrimination. Her career path, she says, was separate from other models’, even though the Supreme Court decreed in 1954 that separate but equal is not equal at all.

Designers seem never to have heard of Brown v. Board of Ed, though, and it took another half century before racial discrimination among models gained public attention. A 2008 Vogue article headlined, “Is Fashion Racist?” prompted a burst of adverse publicity that had industry leaders swearing to beef up diversity practices in 2009, only to lose interest again once the new spring line hit the runway. Since the entire industry is virtually unregulated, no one seems to have proposed target numbers or quotas, and patterns, in fashion, always reemerge. The number of black models at New York’s Spring Fashion Week hit a low in 2013, and the number of white models—83 percent—a high, with some thirteen companies hiring no models of color at all. By Fall Fashion Week 2014, the number of white models had dropped slightly to 79 percent—still not anything close to what a reasonable outside observer would call “diverse.”

The new spring colors, it seems, rarely change. When I ask Meier about racism in modeling, her eyes widen. “It’s part of the job,” she says after a moment. “You develop a thick skin knowing you’re going to be discriminated against because of your physical attributes and race or whatever anyway. You take it as part of the job.”

Throughout our conversation, Meier often pauses to reconsider her experiences. (Unlike Sky, she’s not involved in the movement for model’s rights, which keeps her replies clean of any broader agenda.) “This conversation has opened me up to the idea that maybe some of these things aren’t actually OK,” she tells me. “But…they seemed completely OK. I accepted them. I didn’t know that I couldn’t.”

Not knowing has consequences, of course, which is why the models’ rights movement is important—although only as important as the movement for all fashion workers’ rights. This is substantial: Since the fashion industry as a whole is among the largest employers of women outside the home, it remains the sector of commerce perhaps more responsible than any other for women’s economic repression around the globe.

We tend to see each workforce in the vast apparel industry as distinct—models, retailers, warehouse workers and factory employees each special little snowflakes, doing their part to keep consumers in-style but unique. Yet the entire workforce operates under the same system of global Fordism that governs the race to the bottom in clothing manufacture. The more the cutter and the packer are kept separate, the less likely they are to share concerns about the factory they work in, which is part of why a single garment may be “Made In” several different factories across several different countries.

Likewise, when factory workers are segregated from retailers, warehouse workers and models, fashion workers are unlikely to collectively challenge the global garment industry’s systematic disenfranchisement of women as workers and consumers. Because whether they’re dressed in factory uniforms, sensible slacks or glittery couture, women remain first-order targets of oppression for the fashion industry—which then proceeds to target them again as they line up to pay heavy markups on all the hottest styles.

Still, organizing may not erase the core problems endemic to modeling. “Models are some of the most insecure people I know. Period,” Meier tells me. “And that’s not healed by becoming a more successful model. That’s healed by getting your ass out of it, completely.”

Anne Elizabeth Moore is an award-winning journalist and Fulbright scholar born in Winner, South Dakota. Her long-running comics journalism series on Truthout, Ladydrawers, just ended a close look at connections between sex trafficking and the garment industry, which will be collected into a book in 2016. She lives in Chicago.