She was the first person I spotted when I walked into the room. She sat behind a school desk, two thick black braids, denim overalls resting over a Gap T-shirt. Her skin, not entirely like mine, had a reddish undertone. She wasn’t half-black like me, I was sure of that. But since we were at Shul, I determined she was Jewish like me. And I’d never met another Jewish person who wasn’t white.

I walked over to her. I wasn’t cool. I was overeager. I wanted to be her best friend.

“Hi, I’m Collier!”

“Sadye,” she answered cautiously.

We graduated to phone calls, play dates and sleepovers. She introduced me to her friends. Even at 10 years old, she was self-possessed, and she seemed to have inherited an incredible sense of humor from her mom, Pam, who never made me feel like I was a little kid, and told me jokes I knew she was also telling her girlfriends.

I was younger than Sadye, only by a year, but when you’re nine, that’s a big deal. I took cues from her: Jellies and corduroys were cool, curly hair was not. And when she told me I was only one of two friends who knew she was adopted and that it was a secret I should never, ever tell anyone, I complied. Maybe she told me because that first time Sadye and I met in Shul, she saw a little of herself in me. I’m also brown and I’m also adopted.

But there was a giant difference between us: Unlike me, who was born in the United States, she was born on a farm in the middle of a civil war in El Salvador.

Sadye isn’t alone: 84 percent of children adopted internationally are a different race and ethnicity than their adoptive parents. In 2013, 7,094 children were adopted from more than 90 countries. China, where 2,306 children were adopted by Americans in 2013, was the most popular site for transnational adoption, followed by Ethiopia, Ukraine and Haiti. International adoption has steeply declined in the last decade, but it isn’t disappearing.

Neither are the intense psychological challenges international adoptees of color face, challenges that most adoption agencies and parents don’t truly address. The naturalization process for international adoptees of color requires no visa, no green card, no citizenship test. These children become instant Americans with instant, and often white, American parents. But even though paperwork erases their immigrant status, the overwhelming feeling of being an outsider can linger for years. Earlier this month, the New York Times magazine ran a story about South Korean adoptees returning to their birthplaces, in search of their “kin” overseas. “We didn’t have a choice about what happened to us,” one adoptee said, describing her relief at being able to “live on your own terms.”

But for most transnational adoptees, it isn’t as simple as returning to their motherlands. Instead, their first impulse may be to bury these feelings as deeply as possible. As we got older, Sadye’s secret became an elaborate ruse I had a hard time keeping up. Once, during a free period in high school, a mutual friend asked me about Sadye’s Dominican dad. I reflexively scoffed at him: “Sadye doesn’t have a dad.” (Pam, who is white and Jewish, adopted Sadye on her own.) I quickly realized my mistake. “Oh yeah, I forgot,” I said.

“I felt ashamed that I was a little different from the beginning,” Sadye told me at her apartment recently. Not “like my mom had done something wrong,” but like “I’m not a real family or I’m a weird family.”

When agency-sponsored international adoption took off after the Korean War, nobody was thinking about identity or self-esteem. The 1950s obsession with morality and traditional family values is what propelled the spike in adoptions and orphan sponsorships. A Los Angeles Times advertisement from the era framed adoption as a moral duty for decent Americans:

Many inquire, ‘How can I help Korean Orphans?’ Although few can bring them to this country, YOU can be a Mother or Daddy to your own child in a Christian orphanage in Korea….Yours for the asking! Clip and send away for brochure, ‘How to Adopt an Orphan.’

Wholesome Christian values nicely aligned with the paternalism of international adoption. In 1955, a Christian couple from Oregon named Harry Holt and his wife Bertha welcomed eight children from South Korea onto their farm. Since the Korean War produced thousands of orphans—many the children of American military men and South Korean women—the Holts got the bright idea to found an adoption agency for American parents seeking to adopt orphaned Korean-American children.

In the 1970s, the appeal of international adoption was less about being a good Christian and more about the dearth of options back home, now that birth control was widespread and abortion was legal. “There was a dramatic decrease in the availability of infant children domestically,” says Richard Lee, professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota. “It was a supply-and-demand issue.”

The majority of parents adopting transnationally have been white ever since World War II. According to Lee, 90 percent of adoptive parents currently pursuing international adoption are white. And the diversity training requirement for parents seeking to adopt transnationally is a minimum of 10 hours, hardly enough time to teach about a lifetime of challenges.

Even in an age of increasing race awareness and cultural sensitivity, the prevailing assumption about adoption tends to be: “You were given a loving family—shouldn’t that be enough?” In a recent essay on The Toast, transnational and transracial adoptee Nicole Soojung Callahan recalls how people had told her to “be thankful for it.” She was, but it took her a long time to reconcile her “missing heritage and history” and abandon the feeling of needing to be grateful. “I understood from a young age what I was supposed to be: happy, agreeable, quiet, and grateful,” she writes. “No scars, no holes, no chip on my shoulder.” That’s a tall order for someone thrust into a minefield of identities.

Sadye tells me Pam did the best she could: “She bought me dolls, a Latina babysitter, I spoke Spanish as a kid.” But it didn’t cure her discomfort. “If you have shame about everything you’re doing, it makes everything you do really difficult.”

Of course, the experiences of transnational adoptees of color aren’t uniform. Jackson Walker, 19, adopted at four months old from India by a white couple, tells me he doesn’t remember feeling too different from his peers in his overwhelmingly white Minnesota suburb. “In elementary school it was like ‘Oh, you’re from India, that’s awesome.’ It wasn’t until sixth grade “when it started to come out…when everyone was trying to figure out who they are.”

The timing of Jackson’s lightbulb moment isn’t unique. Lee says by about 10 years old, children generally develop the cognitive maturity to understand why they are being treated differently because of their race and background.

Jackson says his parents were proactive about teaching him about his heritage. They’d get books from the library or alert him when India was in the news. Jackson’s parents also took him and his two siblings (both adopted from India) to meetings at Parents of Indian Children, a support group in Minnesota, and to a camp in Colorado that catered to families of children adopted from India. The author of the New York Times magazine story, Maggie Jones, similarly describes attempts to do “the right things” for her adopted children, like traveling back with them to their origin countries.

Jackson’s parents addressed the possibility of discrimination early on in middle school, but it wasn’t until high school that he realized it was “a bigger issue” than he previously thought. Fortunately, his parents “never once tried to play down any of my concerns.”

But not all parents are like Jackson’s. Even though most adoptive parents are aware of racism, Lee says parents often don’t address it. “Parents may intend to address these issue with their children, but they may not be equipped to know how to do that,” he says. Even doing the “right things” may not be enough: Workshops and culture camps address ethnicity and heritage, but not necessarily race. And while that does get children more comfortable with their ethnicity, Lee says, “it doesn’t necessarily help them to understand the transracial experience.”

There are no comprehensive studies comparing the experience of immigrant children to transnational adoptees. But Lee’s research concludes that Korean adoptees have a lower sense of ethnic identity than their immigrant peers. “There were times where I was around Dominican people who had a very strong sense of their background,” Sadye says. “African-Americans from central Harlem, Bronx backgrounds. I felt like I wanted to have some sort of that as well.”

It’s not that Sadye was raised void of ethnic identity: She was sent to Jewish summer camp and Jewish day school. But Sadye hankered for an identity that extended beyond the boundaries of whiteness. To be raised with the extraordinary privileges of whiteness without looking the part confused her. And Sadye wanted to access the part of her that looked more like her.

Race might not be real, but the experience of race is as real as it gets. From a very young age, Sadye experienced race as everyone saw her: a brown-skinned girl with a white mom. And when there was no one else around that had her same moles, her same hair, her same El Salvadoran background, she internalized it as freakish, as abnormal. As Sadye went from one elite public school to the other, she collected a bevy of white friends—none of whom looked anything like her.

“I always felt a deep sense of ugliness,” says Sadye, and the more conventionally beautiful the friend was, the uglier Sadye felt. Realizing you’re different from everyone, even your parents, leads you to question standards of beauty and whether or not you fit.

I was born in the United States. My biological mom is white and Jewish and my biological dad was black—the inverse of my adopted parents. I was not a beacon of self-confidence, but I knew I was black, and I knew I was white and Jewish. I knew I was born here and not on a foreign soil where people speak another language I don’t know. I was adopted, but I recognized myself in my mom. And also in my dad. When I wasn’t in the mood to tell people I was adopted, I didn’t feel like I was lying. And nobody could tell, anyway. I could hide in plain sight.

I am who I say I am, I would tell myself. There’s no such thing as “white” or “black” blood, but I always imagined there was. For a long time it made me feel authentically black and authentically white.

I have always suffered from terrible bellyaches. A therapist told me I probably stored my stress there, that it was psychosomatic. But my dad insisted I find out my medical history. I first found out my mother’s name, Ellen, when I was 20 years old. I decided to write her a letter. What I got in return—a confusing and lengthy scrawl—made me uneasy. After some years I contacted her sister, Deni, who confirmed for me my biggest fear: Ellen is a schizophrenic.

Six years after I found her name, address and age, I mustered up the courage to meet her on the Highline in New York City. I asked her who my father was and she said she couldn’t remember but that he was definitely black, a businessman from New Orleans with a few kids. Boys.

My adoption was closed, which meant that all records about my biological parents were sealed. I wasn’t allowed to even call the adoption agency and hospital I was born in and inquire about my biological mother until I was 18 years old. By the time I did that, the adoption agency had shuttered its doors and the hospital informed me they could only hand over the records if my biological mother had given them permission. She hadn’t. We had to hire a private investigator.

Sadye went on a search for her biological mother, too. Born in 1984, as a brutal war raged in El Salvador, Sadye didn’t know much about the circumstances of her birth, or even where her biological mother was.

After a long and arduous hunt, she finally found her biological mother in “el puro campo”: “the real country.” Finally, everything started to make sense. “I don’t have a lot of physical ailments,” she says. “That has always been a mystery to me—why don’t I get a cold? Or get the flu? And why do I have all my wisdom teeth?” When Sadye stepped onto her birth mother’s farm, she saw “fresh fruits and cows and chickens running around, and hella dogs.” The fact that she’d spent the first eight months of her life there had seemingly “armed me with some strong foundation for health.”

There were other things about meeting her birth mother: their uncanny resemblance, their shared spirituality, feeling as if she got her “fighting spirit” from her biological father after hearing that he was a guerrilla who died fighting the U.S.-backed Contras. Sadye says it was the “little things” that helped her “find some sort of connectedness. It was really valuable for me. And it really armed me with a stronger sense of identity—of who I am and where I came from.”

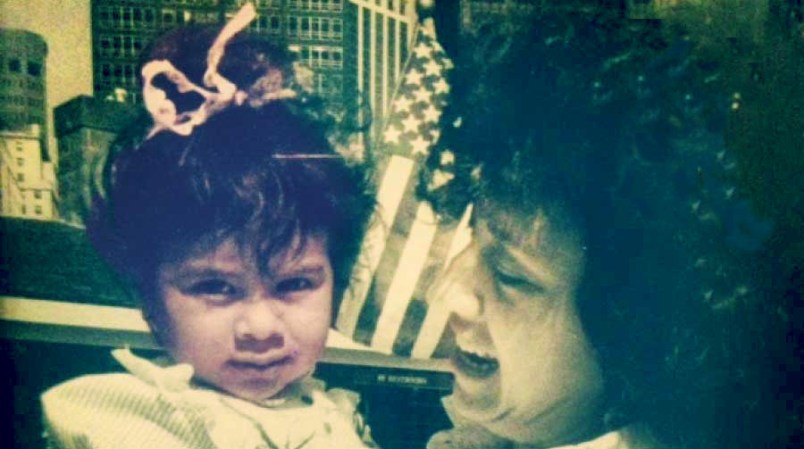

Sadye and her biological mother, 2009

Nowadays, fewer domestically adopted kids have to set out on an odyssey to find their parents because open adoptions are becoming the norm—most adoptees know exactly who their biological mother is, and in many cases form a relationship with them. According to the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, “closed” infant adoptions are now a silver of all adoptions overall (about 5 percent), with 40 percent “mediated” and 55 percent “open.” These new customs are changing the way family looks, and with the right policies in place, they could provide a model for transnational adoptions, too.

When I ask her if she is resentful of her mom, Pam, she gives me a decisive “no.” For Sadye, finding her biological mother on her own helped her take control of her identity. But perhaps if Sadye had known these details from a young age, if “my mom took some ownership over that culture as if it was her own the same way I took ownership of her [Jewish and Greek] culture,” it might have led to less shame.

It’s hard to fault any good and present parent for not being thoughtful enough. But white parents can make the reality of racism in America easier to talk about. As one adoptee put it to Jones: “You need parents…who can say: ‘You might experience some of this. I’m sorry. We are in this together.’ ” When it comes to race, Lee says, “prospective parents and adoptive parents need to be more uncomfortable than comfortable.”

Seven years before she met her biological mother, Sadye stood on the Oberlin College quad with Pam as a prospective student, feeling awkward and out of place, as prospective students tend to feel. A group of students—all women of color—walked right up to her. Her mom made herself scarce and Sadye, then alone with these strangers, remembers feeling instantly at home. One of the women casually asked Sadye, “What are you?” Surprising herself, she replied, “I’m El Salvadorian… but I’m adopted.”

Just like that, it was over. She was “out.”

“And then they said ‘cool’ and the conversation kept going!” she says. It was the first time she’d ever told anyone so openly, so decisively. An immense weight was lifted from her shoulders.

We’re slowly moving away from that stodgy, 1950s idea of adoption and family. But I’m hoping it can move a little faster, so that the next generation of Sadyes will be surrounded by a society of people who consider her normal. I have an intense desire to take away all Sadye’s pain—of not belonging, of feeling ugly, of not knowing where she came from. I imagine what it could have been like for Sadye as a young girl learning Spanish with Pam on a beach in El Salvador. I imagine them devouring pupusas, laughing. I imagine Sadye casually telling her kindergarten friends that she had been adopted from thousands of miles away. And then they say, “cool,” and the conversation keeps going.

Collier Meyerson is a writer and producer living in Brooklyn.