The other day, I pointed out the pink sunset between the cluster of bare winter trees behind our house to my five-year-old daughter, and she turned to me, her face blank and said, “Is that real?”

“What do you mean, honey? It’s the sunset.”

“No, I mean is that fake, like is this something we see on TV, or is it actually happening?”

I thought I’d done a better-than-average job striking a tech balance for my kids—I take them on hikes, craft illegible chalk drawings on the sidewalk, have a no iPhone rule for the beach—but my daughter’s confusion bothered me. Yes, she’s five. Yes, kids that age sometimes confuse what they see on TV and what’s real. You can’t touch a sunset, so I couldn’t explain it to her in the physical way, but I emphasized that we weren’t staring at a screen. That what she saw in front of her eyes was in fact, real life.

I thought about this moment when I read Alison Slater Tate’s Washington Post article last week about what it’s like being a parent in the age of iEverything. Tate groans about how challenging it is to get her kids to look up from their phones just to acknowledge nature. “We can try as hard as we want to push back and to carve space into our children’s lives for treehouses and puzzles and Waldorf-style dolls,” she writes, “but in the end, our children will grow up with the whole world at their fingertips, courtesy of a touch screen, and they will have to learn how to find the balance between their cyber and real worlds.”

Tate’s essay is the latest in a wave of modern critiques about how the onslaught of our digital world will be the end of us. This week, Information Age’s headline blared that the digital reborns are taking on the digital natives. This doomsday map illustrates how humanity keeps discovering brilliant new ways to destroy itself. And if Newsweek’s threat of Cyberwar doesn’t want to make you escape to a computerless cabin in the woods, I don’t know what will. It’s a point that’s made over and over and over again.

There’s part of me that sympathizes, but something about the panic rubs me the wrong way. This constant commentary isn’t just unsettling, it’s fear-provoking. It’s like we’re living a written history, a techno play-by-play, instead of what Matthew McConaughey would recommend (which, I would never say in a million years…okay fine, maybe once): Just Keep Livin’.

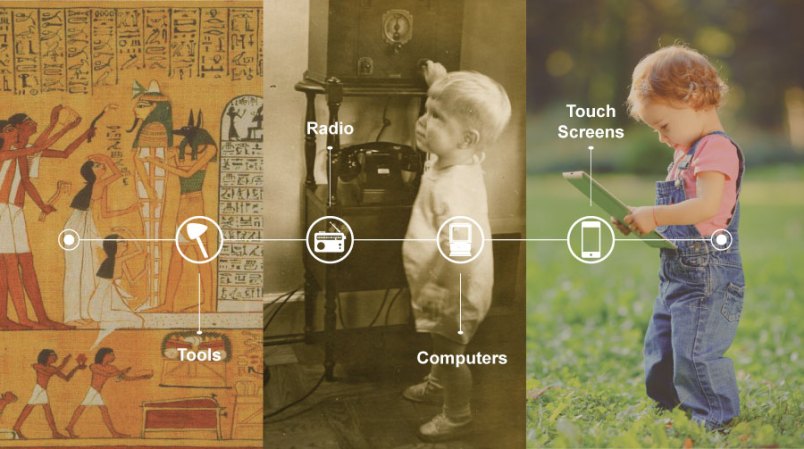

Even though our technology is new, our anxiety about it is not. And it’s this same anxiety that connects us to the growth and innovation of every other era of human history.

Each generation has a story to tell about a gadget that seemed modern and crisp and also utterly daunting. When my mother watched Milton Berle on her set in her two-family house in Brooklyn, it was the first television set on her block. I had the first Atari in my neighborhood, which was why my cute neighbor wanted to hang out at my house. All you have to do is watch “Downton Abbey” to see how uncomfortable tech advances have made us in the past 100 years—in a recent episode, Lord Grantham and Mr. Carson melted down when Lord Grantham’s much younger niece asked for a “wireless” (a radio) to listen to a broadcast of the king’s speech. “I find the whole idea kind of a thief of life,” Grantham said. “That people should waste hours huddled around a wooden box, babbling inanities at them from somewhere else.”

Look at big-impact inventions: Technology writer George Dyson credits cement as a crucial first-millennium innovation, telling the Atlantic that “it was the foundation of civilization as we know it—most of which would collapse without it.” But isn’t it possible some Egyptians were all, Hey, what about limestone? Our society will never be the same.

Granted, the changes of the past five years have moved quicker than any time in history. My son, age 11, didn’t have the luxury of playing on an iPhone when he was a toddler, but my daughter, five years younger than he, already knew how to use a few of the early apps by the time she was 18 months old. Tech has had such tremendous breakthroughs since 2010—tablets, motion sensor game consoles, agricultural drones and brain mapping—that the ones screaming “Remember when?” are practically newborn babies.

But even though it’s faster now, our awe over technology allows us to tap into an intrinsic part of human history. In a way, that’s strangely comforting. My son constantly reminds me, You know nothing about life because you grew up in the seventies, but in the very near future, someone is going to dismissively say to him, You’re from the aughts. It’s all different now.

In the end, though, nature still has a magnetic pull. Just the other day, “War Games,” the OG of hacker movies, was on TV. A pivotal scene shows Dr. Stephen Falken, a character based on Stephen Hawking, learning that the computer he created for NORAD—the kind of intelligent computer that can think for itself—is about to launch Global Thermal Nuclear War and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop it. Just before Falken helps save the world, he lectures Matthew Broderick and his girlfriend about human evolution:

Once upon a time, there lived a magnificent race of animals that dominated the world through age after age. They ran, they swam, and they fought and they flew, until suddenly, quite recently, they disappeared. Nature just gave up and started again. We weren’t even apes then. We were just these smart little rodents hiding in the rocks. And when we go, nature will start over. With the bees, probably. Nature knows when to give up.

Until our technologies destroy it, nature will endure. We’ll always be forced to look up from Twitter or stop scrolling through whitewashed Swedish homes on Instagram to catch a sunset or a full moon. Even my daughter’s question seems much more innocent in this context—less spawned from the evils of technology than child-like curiosity. “This is so beautiful,” she seemed to be saying. “How can it be real?”

Hayley Krischer is a freelance writer based in New Jersey. Her work has appeared in The Toast, The Hairpin, Salon, The New York Times and other publications. You can find her on Twitter.