Having grown up in the Northeast, where mass deforestation through the 1800s rendered our woods decidedly subdued, I have a soft spot for the wild, overgrown landscapes of certain warmer American climates. I always know I’m far enough away from home when I start to see the curling tendrils and broad leaves of kudzu devouring abandoned billboards on the side of the road.

Kudzu, known as “the vine that ate the south,” is a major player in the ruin porn canon and therefore inextricable with a certain conception of the South. If left unpruned, it can grow a foot a day and climb up to 100 feet, smothering everything in sight—other plant species, absolutely, but junked cars and entire buildings, too. In the unlikely case that the plants do wither, it’s like a zombie movie: New growths use the dead vines for support in their relentless upward climb. In folksy legends, kudzu covers humans as they sleep, creeps into windows at night.

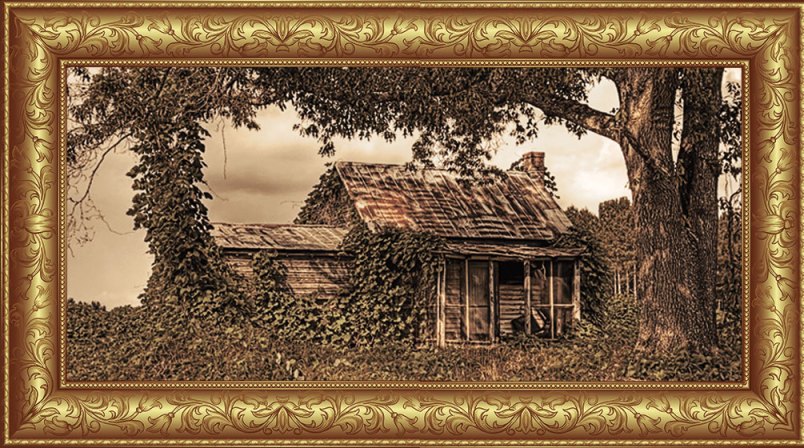

The woody, ravenous vine blankets the states of Alabama, Georgia, Florida and Mississippi most heavily and features prominently in representations of the American Southeast; it’s a staple in the moody black and white landscapes Sally Mann photographed for her book Deep South. Without it, the lush and dilapidated areas that have inspired television’s recent Southern Gothic revival—see True Detective’s spooky, overgrown Louisiana—would be relatively bare. As a metaphor, it’s used abundantly—essayist John Jeremiah Sullivan once described reality TV as having “gone kudzu”—and as a symbol of nature’s inevitable triumph over the civilizing efforts of man.

Kudzu in Wake Forest, North Carolina. Photo credit: smky bear on Flickr

In one of the most oft-quoted passages from Chuck Palahniuk’s nihilistic alt-bro fantasy Fight Club, he describes a Chicago overrun by primitivist ex-catalog shoppers: “You’ll wear leather clothes that will last you the rest of your life,” he writes, “and you’ll climb the wrist-thick kudzu vines that wrap the Sears Tower.” Palahniuk’s vision of a future America overrun by rugged, loin-clothed survivalists may not be the most plausible, but his ecological observations probably are. As the journalist Alan Weisman speculates in his book The World Without Us, were humans to disappear entirely from the planet, “long before the vacant houses and skyscrapers of America’s Southern cities tumble, they may have already vanished under a bright, waxy green, photosynthesizing blanket” of kudzu.

In some cases, it’s even added to the mythic image of the antebellum south, framing the landscape as charmed, lush and gauzy. At times its resilience is used as an allegory for southern gumption—or as a threat, as in one bizarre postcard that threatens Confederate revenge by planning kudzu seeds “up nawth.” But really, kudzu’s predatory root systems and curling vines didn’t make an appearance in Confederate states at all. Romantic it may be, but it’s less a decorative touch than a biological menace—a “noxious weed,” to use the official Department of Agriculture term. And it’s not antebellum, either; it wasn’t introduced to the U.S. until after the Civil War. Like so many images on which an aggressive sense of southern identities rests—many under renewed scrutiny, given recent national debates—kudzu’s place in local imagination is a fiction that took more than a century to write.

Kudzu first arrived in the United States from Japan during the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Expo, where an elaborate Japanese pavilion was constructed among 42 acres of agricultural stands; the vine was showcased again in 1883 in New Orleans. At the time, interest in cultivating new crops for American farmers was high—obviously, Southern farms were grasping for models that didn’t rely on mass enslavement. A late-19th century fascination with Darwinism and species categorization contributed to America’s interest in foreign plants, too.

Soon after kudzu was first introduced, Congress founded the Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, which sent botanists on years long trips abroad. In the ensuing decades, David Fairchild, the office’s first director, would introduce more than 20,000 exotic plants to the U.S., including bamboo, horseradish and cherry trees. Though Fairchild himself didn’t introduce kudzu, he did encounter it on his extensive travels, and was likely the first to note that it was near-impossible to get rid of the stuff. But by the time he published his warnings of kudzu’s invasive potential in 1938, hundreds of thousands of acres had already been planted.

Originally, the vine was marketed as an exotic, ornamental plant useful for shading porches—one Good Housekeeping advertisement describes it as having blossoms “a shade of purple and deliciously fragrant.” Mass adoption began around 1925, when C.E. Pleas, a Florida farmer, found a more pragmatic use for the plant. His pamphlet, “Kudzu—coming forage of the South,” describes the vine as a neverending, continuously regenerating source of livestock fodder, similar in nutritional value to alfalfa. The enterprising Pleas and his wife sold kudzu through the mail and are memorialized in a plaque in Chipley, Florida, that makes no mention of the vine’s official categorization as a noxious weed. Throughout the early part of the 20th century, kudzu continued to be revered as, in the words of one Popular Mechanics article, “a perennial legume of most marvelous growth and hardiness.” By 1934 there were an estimated 10,000 acres in cultivation.

From a 1922 issue of Popular Mechanics

During the Depression, the newly founded Soil Conservation Service took to promoting kudzu aggressively as a solution to erosion, most notably in the Dust Bowl—the vine’s sturdy roots and tendency to flourish in fallow soil made it an ideal candidate. The agency raised an estimated 100 million seedlings of kudzu between 1935 and 1942, and civilian workers were hired to plant the vine in highways and ditches across the South. In some cases, the government paid up to eight dollars an acre to farmers who planted it. Not long after, the “gentleman farmer,” who was the kudzu plant’s most vocal supporter, started the Kudzu Club of America. Its goal: to plant 8 million acres of kudzu in South.

A 1919 article in Fair Play, a newspaper in Sainte Genevieve, MO

A 1919 article in Fair Play, a newspaper in Sainte Genevieve, MO Channing Cope, Georgia farmer, author, radio personality and editor for the Atlanta Constitution, sounds like a Southerner in the style of John Goodman’s Big Dan: massive, talky, hard-drinking, and nearly always dressed in a seersucker suit. Cope was one of the most widely recognized farm personalities in Georgia in the ‘40s, and used his daily column and radio show—not to mention his various books on the subject of farming—to extol kudzu’s virtues as a solution to overfilled and dried out soil.

Cope’s optimistic vision of a future South, one redeemed and verdant, refined and productive, appealed to an economically depressed region. Kudzu was a major part of that plan. In a Readers Digest story from that time, a government agent is quoted as remarking, “What, short of a miracle, can you call this plant?” In the same story, it’s reported that scientists are hard at work creating more cold-resistant strains of the plant to import up north. Luckily, it appears that particular project never came to fruition.

There was no single moment when the perception of kudzu shifted from adoration to revulsion—likely the aggressive push to plant it across the South worked too well, and farmers realized how impossible to eradicate it was. Even now, it can take ten years and a cocktail of pesticides, not to mention the labor required to dig up and destroy the spindly roots, to get rid of the vine. The USDA claims the plant is spreading at a rate of 120,000 acres a year; since 2000 it’s been sighted as far north as Oregon and in every borough of New York.

Kudzu shows up in Chicago. Photo credit: moominsean on Flickr

Oddly, Channing Cope kept pushing the plant until his death, even after the USDA removed kudzu from its list of recommended crop covers in 1954 and a poem published in the New Yorker dedicated to kudzu plants called them “green, mindless, unkillable ghosts.” Once, a friend of Cope’s told an academic that the kudzu vine itself was minorly responsible for his death; according to the (very likely exaggerated) story, Cope refused to trim back the vine on his property until it overgrew his property completely. Kids from the town, looking for a place to make trouble away from parental view, would park on his land, protected by the plant’s dense cover; the friend claims Cope died of a heart attack trying to chase the wayward teens away.

Kudzu enjoys a profile ranging from vitriolic hate to begrudging resignation to anodyne affection. Across the southeastern United States there are balls and festivals named after the vine, despite USDA claims the agency spends around $6 million a year on control and eradication. Like a controlled substance, it’s illegal to transport kudzu, which can choke and kill entire forests, across certain state lines. In the late ‘90s, one Florida town became the first to fine landowners for letting the plant creep into a neighbor’s property.

More recently, the vine has inspired eccentric local celebrities to reimagine its purpose. Some claim kudzu powder is a powerful hangover cure, others that its leaves taste fantastic when fried. In North Carolina, the “Kudzu Queen” and her husband have cultivated acres of the weed to turn into folksy crafts: wreaths, baskets, potato chip-like snacks, jellies and quiche. After all, it’s not as if the vine is going anywhere. A few years ago, the University of Kentucky launched a study to see if goats would be an effective method of eradicating the vine that ate the South. The results were largely inconclusive.

Molly Osberg is a writer based in New York. She’s on Twitter @molly__o.