This is part two of a four-part series at The Slice called “End of the Road,” about America’s waning love affair with car culture. Read the first part here.

It’s 5:30 p.m. on a warm evening in central Phoenix, and Denise Wilson is looking at her reflection in the mirror. Next to her, on her bed with a hot-pink comforter, lie her work clothes for the day: a pair of khakis and a pink polo. She goes into the bathroom to change, and when she comes out, she looks determined. “All ready for the day,” she says.

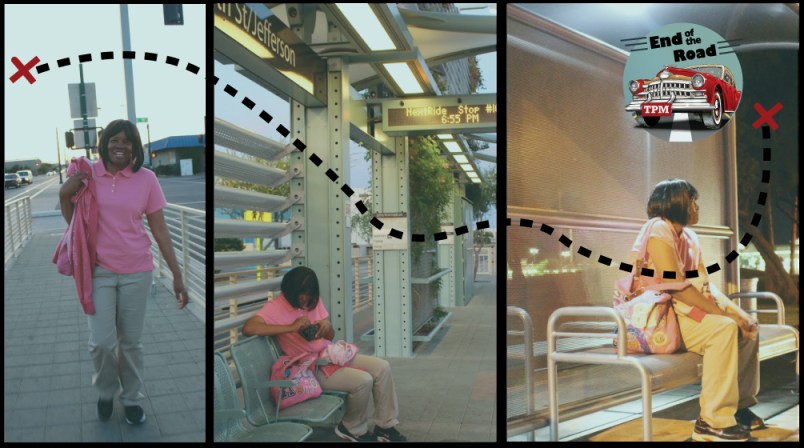

By 6 p.m., she leaves her home to go to her job as a caregiver for the elderly and disabled. Four hours later, she will have traveled less than 30 miles. With the trip back in the morning, faster because there are more buses at that hour, her commute totals almost six hours each day.

The trek takes around 30 minutes by car, a little more if there’s traffic—but 54-year-old Wilson doesn’t have one. She lives in a bridge shelter, a temporary home where she works with case managers to find permanent housing, where she’s been living for 11 months. She shares a room with several other women, calling one neat little corner her own. She’s trying to move on—get a job, save money, find her own place—but it’s been a struggle. A highway-sized struggle.

Since the recession, countless articles have noticed the waning relationship of America and cars. In 2009, Nate Silver wrote a story for Esquire declaring an end to car culture. “For people like me who live in big cities where one does not need a vehicle to get by, there is a certain romantic attraction to this story” of America’s breakup with the car, he wrote. But even he noted a stark cultural divide: “In the real world, of course—outside perhaps a half dozen major metropolitan areas—American society has been built around the automobile.”

Here in Phoenix, not having a car makes you somewhat of a pariah. More than 4.3 million people live in the Phoenix metro area, the sixth-largest in the U.S. by population, and according to the Arizona Department of Transportation, Maricopa County has more than 4.2 million registered vehicles. Even as some cities in the U.S. have seen a gradual decrease of vehicles per household, Phoenix’s numbers remain static. According to a study by Michael Sivak, a professor at University of Michigan, and expert on driving demographics, 9.2 percent of U.S. households did not have a vehicle in 2012, compared with 8.7 percent in 2007. But in the same span of years, Phoenix went from 8.2 percent of households with no car to 8.5 percent.

Phoenix is not alone. Some of the fastest-growing cities in the nation are in the Sunbelt, including San Antonio, Austin, Las Vegas, Raleigh and Charlotte—and they all have a dearth of reliable, efficient public transportation, not to mention dismal walkability and bikeability. Walkscore gives all these places walkable scores below 40 out of 100, declaring them “car-dependent cities.”

Carless freedom is especially hard to come by in Phoenix. People need cars for almost anything, from running the simplest errand to getting to work to going out with their friends. And with temperatures reaching 110 degrees from late April to October, waiting 30 minutes for a bus is something you do only when there are no other options. America’s love affair with the car may be symbolically over, but in the Valley of the Sun, having one is still an absolute necessity.

Wilson gets to her first bus stop just in time, a couple of blocks away from the shelter. To the side, a bus schedule shows how often the bus comes. The weekends are almost bare. When she works Saturday nights, she can’t afford to wait 30 minutes for the bus, so she walks an extra mile to her next destination.

On the bus, Wilson chooses a seat at the front and keeps to herself. Almost 15 minutes later, she gets off and walks to the Metro Light Rail station. Once on the light rail, Wilson gets comfortable. She rides it all the way to the last stop, the longest stretch of her trip.

Phoenix’s 20-mile light rail system runs from central Phoenix, through downtown and east to the cities of Tempe and Mesa. Valley Metro, the regional public transit agency of metro Phoenix, operates 102 bus routes over 18 cities and towns in Maricopa County. Ann Glaser, a Valley Metro public information officer, says there are seven planned light rail extensions which will create a 66-mile system by 2034.

“The Valley of the Sun has a critical need for an expanded transit network,” she says. “By expanding the light rail system to future high-capacity transit corridors, commuters would have greater options for mobility and connectivity.”

For Wilson, this 20-year plan is too little, too late. She needs it right now, but it’s undeniably out of grasp. She wishes she could at least see smaller changes— more frequent buses or regular weekend service, for instance.

Typically, Glaser says, weekday bus service ends between 10 and 11 p.m, so on weekdays, Wilson needs to make sure she is at her last bus stop by 9 p.m. to catch the last ride of the night. On weekends, the service ends at 7 p.m. , so she ends up walking the extra two miles she would have traveled by bus.

“I’ve gotten to know this city fast,” Wilson says. “I ain’t going to lie. When I moved here, I did lose my way home once or twice, but you better learn your way around fast.”

Originally from Detroit, she’s been in Phoenix for a little more than a year. But already she’s run into one of the biggest challenges of life in the desert.

“Here, when you’re outside, you can feel your skin burning,” she says. “I had never experienced something like that.”

With temperatures rising to more than 110 degrees, summers in Phoenix can be grueling. Many bus stops offer no shade, and waiting for the next ride can be a hurdle in itself. According to the Arizona Department of Health Services, more than 1,500 people have died from heat exposure in the state from 2000 to 2012.

When she first arrived to the city, Wilson was staying with a friend who had told her work would be easier to come by in Phoenix. Just three weeks later, she had no place to live.

“One day [my friend] just looked at me and said ‘I just don’t feel comfortable with you here,’” she says. “It still hurts to talk about it.”

Shortly after that conversation, Wilson found herself stranded outside a Goodwill store, a place her friend thought would be able to provide assistance, with nowhere to go and barely any knowledge of the city. She ended up begging her friend to come back and drive her somewhere she could spend the night. After a few nights at a motel, she finally found the shelter where she now lives.

With a background in nursing and 30 years of experience as a nurse assistant, it took Wilson six months in Phoenix to find a job. Now, she feels herself edging closer to the life she wants: Four nights a week, she works 10-hour shifts as a caregiver. Wilson was living with her son back in Detroit and hasn’t seen him since; she says she can’t invite him until she has a place of her own. She does not want to tell him she lives in a shelter.

She also knows she can’t keep commuting for this long and sleeping five hours a day (if she’s lucky).

“Since starting this job, I’ve lost 10 pounds,” she says. “How could I not? I walk so much every single day and barely sleep.” Sometimes her feet hurt so much, she has to call in sick.

The solution? Moving close to work. Wilson works in Gilbert, to the southeast of Phoenix, once established as an agricultural town. Now it’s a flourishing and populous community with a median household income of $80,000, one of the largest in the state, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. To get to her job, Wilson walks along Gilbert Road, a wide avenue in the heart of town that houses most museums and historical buildings.

It’s a clear contrast to the neighborhood in which she lives. The shelter is located in the East Van Buren corridor, an area historically known as Phoenix’s red-light district. The city and community task forces have attempted to revitalize the area and they have seen some success: Robbery, drug offenses and assault-related charges are down. Despite this, the corridor remains a derelict streetscape.

Still on the light rail, Wilson counts the stations. She is 13 away from her destination. The ride takes 40 minutes, without delays (which happen often). By the third station, a man has become belligerent and another rider stands up to confront him. Someone presses the emergency button. The voice on the intercom asks what the problem is. On the next station, a security officer is already waiting to board.

It’s been 10 minutes by the time the man agrees to exit the light rail.

“I don’t get scared over stuff like this anymore,” she says. “Instead, I get annoyed because if I’m even a few minutes late, I might miss my next bus. It can end up costing me a lot of time, but you know? You do what you gotta do to get ahead.”

Tonight, she exits the bus with plenty of time to spare. After checking the time (a little past 8 p.m.) she decides to walk to a nearby supermarket and get a soda. She needs the energy, she says.

Wilson is, of course, not the only carless person in Phoenix. But not all of them are daring to travel daily from the city to the suburbs while relying solely on public transportation. Quinn Whissen and Ryan Tempest are in the Nate Silver camp: car-free because they want to be.

Whissen and Tempest are co-founders of a community engagement urban awareness group called This Could Be Phoenix. A marketer and designer, Whissen works from home and meets weekly with clients, who are usually willing to make concessions and meet her places near light rail stops. Tempest, an architect, rides his bike and the light rail to get to work each morning, but the trip is only 15 minutes.

“I live downtown, my work is downtown, my friends are downtown, and if everything is downtown then it makes sense for me not to have a car,” Tempest says. When the pair has to travel outside downtown, they use a car service or a Zipcar. But they have made the conscious decision to spend most of their time in downtown Phoenix only.

Whissen and Tempest are quick to admit there is a clear difference between them and people like Wilson, who don’t get a say on whether or not they own a car. “We are fortunate to be able to make these choices intentionally,” Whissen says.

For Wilson, where she lives depends solely on one factor: affordability. Chances are, she won’t be able to live, work and socialize in her own neighborhood, and without a car, she will be forced to keep relying on public transit.

The public stigma is a factor, too. “A lot of the infrastructure, the regulations and the attitude toward people who don’t have a car is very second-class,” Whissen says.

Tempest says the issue is bigger than just an inadequate transportation system. Suburbs and cities are developed around the automobile and that will inherently become the mode of transportation.

“There’s actually a lot of negative aspects to that planning system,” he says. “And now the choices are so limited to those who don’t have access to a car or choose to don’t have a car.”

Members of the Phoenix City Council agree. In March, the council approved a citywide transportation plan, which would increase the city’s sales tax from $.04 to $.07. The tax would be in place through 2050 and would bring an estimated $30 billion to fund public transit. The plan is slated to be on the ballot in August.

Two and a half hours after leaving home, and after her soda break, Wilson gets ready for her second bus of the night. The ride to her next destination is barely 15 minutes long, but the bus she catches from there won’t come for another 30 minutes.

“The city can be scary when you don’t know anyone,” she says as she sits in a completely deserted bus stop, the streetlight barely illuminating the stop. She says it’s like this most nights, and she prefers it. Once or twice, she’s been approached by strangers and, trembling, she talks about a man who once grabbed her hand and tried to pull her away.

Finally, it’s 9 p.m., and Wilson gets on the last bus of the evening. Ten minutes later, she is off the bus. But her journey is not over. For another 30 minutes, she walks. Slowly, because her leg can act up sometimes, but she’s determined to make it before 10 p.m. when her shift starts.

She is a few minutes early as she closes the door behind her, ready to start work. Tomorrow morning, after working 10 hours straight, she will make the trip home.

Paloma Baltazar is a Phoenix-based journalist. Born and raised in central Mexico, she moved to the U.S. to attend Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, where she served as the news editor of The State Press, ASU’s student media organization.