On the day I meet Steve Pierce, his forehead is raw and glistening from just having been blasted by liquid nitrogen, treatment for the skin cancer which seems to ail virtually every old sun-blasted rancher like him. “Feels like just about the world’s worst ice cream headache,” he complains.

We’re driving his giant red GMC Yukon SUV from Prescott, Arizona, the idyllic desert mountain town where Barry Goldwater announced his 1964 run for president, to Pierce’s ranch 30 minutes away, where plump cattle graze on bleached, windblown grass next to the little chapel where his daughter was married. The sprawling property is called Las Vegas Ranch, and it’s been in the Pierce family longer than the gambling town has been around.

A Republican lifer in Wranglers and cowboy boots, Pierce is his party’s old school ideal: a self-sufficient small-business owner living off the land, growing steaks for people who can afford them. He’s also a prominent Arizona state senator, formerly president of the senate and majority whip.

So it’s somewhat surprising that he has invited me to his home district in order to sell me on the benefits of Obamacare.

Here in Yavapai County, most everybody you’ll meet is Republican. In 2012, Mitt Romney received nearly two votes here to each of Obama’s. And yet in this rural red county in a very red state, it’s only taken a couple of years for federally-subsidized health care to quietly seep into the hinges of everyday life and governance. The rate of sign-ups for the program in the county has nearly doubled from 2014, when 22 percent of the area’s potential market share chose a plan through the federal exchange, to March 2015, when 43 percent did, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The latter figure ranks the county sixth among 54 areas in the state in percentage of the potential market share which has signed up, outranking far more liberal areas in Arizona.

This is what Obamacare Country looks like.

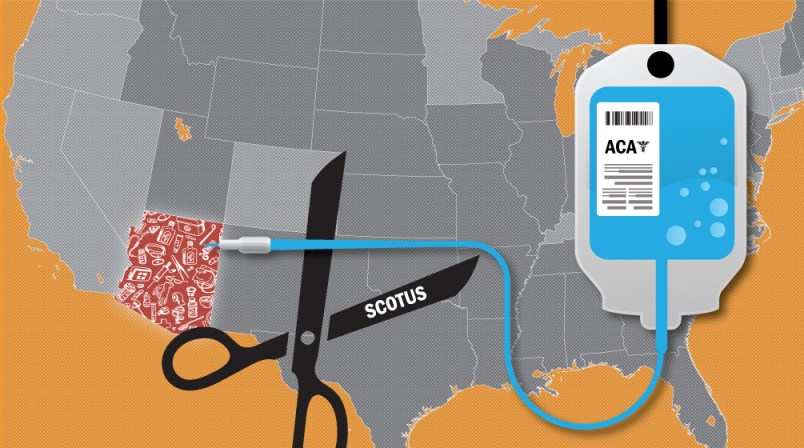

After a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 that allowed states to opt out of Medicaid expansion, the Affordable Care Act is once again in danger of being undercut in court. In King v. Burwell, the Supreme Court is considering a lawsuit on the legality of federal health care subsidies in Arizona and 33 other states that have not set up their own healthcare exchanges. According to data from Kaiser, 6.4 million Americans could lose subsidies across the country by the end of June, including 126,506 in Arizona, where roughly 77 percent of those who have signed up for the ACA receive subsidies.

The possibility that the country’s highest court could kneecap the ACA has Republicans strategizing feverishly, and often at odds with each other, about how to lessen the backlash from millions of Americans who would have to pay more or lose health care coverage. In Arizona, Republican Governor Doug Ducey has pre-emptively dug in his heels, signing a law designed to prevent the state from setting up its own exchange in order to keep ACA subsidies coming in. Yavapai County acts as a pop.-200,000 lab slide of a phenomenon occurring in conservative regions around the country, where party politics have been pitted against everyday pragmatism, often resulting in spectacular GOP infighting.

Ducey’s predecessor, Jan Brewer, was once the darling of the right wing, including for her harsh stance on health care. In 2011, she helped close a budget gap by slashing Medicaid eligibility in the state. But she stepped into the conservative maw less than two years later when she began to push for Obamacare-funded Medicaid expansion. “Jesus had Judas,” Maricopa County Republican Committee chairman A.J. LaFaro testified at the time. “Republicans have Governor Brewer.”

When Pierce backed up the governor with a vote in the state senate, he became a magnet for the ire of conservatives. The powerful conservative group Americans for Prosperity, backed by the billionaire Koch brothers, listed him in its “Hall of Shame” for his “disgusting” act of “betrayal.” County Republicans voted to censure him, a largely symbolic gesture of scorn.

Brewer, whose gubernatorial term expired in January, says she still has “the scars on my back” from clashing with Arizona’s Republican hardliners. “We have some really, really—I don’t even know if they’re right-wing Republicans, they’re libertarians,” she tells me in an interview in a downtown Phoenix law office. “They’re anarchists. And they’re mean!”

Probably no Republican politician in Arizona has poked the far-right flank of the party with quite as much abandon as State Senator Steve Pierce. Once an invited speaker at Tea Party rallies and the owner of about five dozen guns, Pierce agreed with Arizona’s notorious Senate Bill 1070 that forced aliens to carry registration documents, and he is a climate change skeptic. (“I tend to just believe we’re in a severe drought,” he told me.) Yet despite these conservative bona fides, he lost the senate presidency after clashes with the party and was censured by Republicans for his support of federally-funded health care.

Pierce’s bouts with his own party have been legion: He’s voted against a bill which allowed private property owners to build their own gun ranges; last year, he asked then-Gov. Brewer to veto a polemic “religious freedom” bill allowing Arizona business owners to discriminate against gays, after he had initially voted for it; and this March, he helped kill a bill that would’ve allowed Arizonans to carry guns into public buildings, such as courthouses or schools. After one such standoff with fellow Republicans—over his vote with Democrats on an amendment requiring background checks for purchases at gun shows—Pierce says he “told them all to go fuck themselves” and bolted to his ranch, where he was deluged with angry emails from pro-gun activists around the country.

Ideologically, Pierce is opposed to federally-subsidized health care, which he believes is a government “intrusion” and part of a “huge overreach in federal power” under Obama. But in 2013 when Brewer introduced her plan to expand Medicaid with ACA funds, Pierce seemingly took a surprising tack: He gauged his constituency. His was an aging district with a retiree town for a county seat—the median age in Prescott is around 54—with a financially failing community hospital and a jail overrun with the mentally ill. He says he decided that voting for Medicaid expansion was “the right thing to do. I don’t represent the people on the far right, or the Republicans. I represent everybody who lives out here.”

Steve Pierce on the way to his ranch

Pierce didn’t stand alone; 14 out of the state’s 15 sheriffs, nine of whom were Republican, backed the expansion. One of those sheriffs was Yavapai County’s Scott Mascher, whose own conservative bona fides include vowing not to enforce federal gun control laws, but who argued that the Medicaid expansion would help reduce recidivism and length of stays for mentally ill prisoners. (The lone holdout among the sheriffs was Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who that year was busy losing a federal lawsuit that accused him of racial profiling in targeting Latinos during traffic stops.)

The expansion of Medicaid, following the Arizona legislature’s deep cuts to who was eligible for the state health care program, was a lifeline for dozens of hospitals and medical centers which were in danger of closing because so many uninsured people could not pay. After Obamacare coverage went into effect in January 1, 2014, hundreds of thousands of residents—including those with new Medicaid cards and people with subsidized private insurance—could suddenly pay their bills.

If the Supreme Court rules that federal subsidies are invalid for enrollees in the 34 states without their own exchanges, the loss of health care for up to 126,506 Arizona residents will have a domino effect on health providers in the area. While only subsidies for private insurance are at stake in Burwell, people in Arizona worry that the loss of that revenue will hit clinics hard and threaten some of them with closure, limiting access to health care for everyone, including Medicaid recipients.

It’s an issue driven home at, of all places, the bleak Yavapai County Jail. Sheriff’s office captain David Rhodes shows me the mental health unit, home to mentally ill prisoners who have committed minor crimes akin to vagrancy. According to Rhodes, that has included a homeless man who spent a six-month stint here for defecating in a Prescott bush simply because, with the dismal state of available mental health facilities at the time, there was nowhere else to send him.

Now that health care coverage is more widespread, Rhodes has implemented a surprisingly progressive program, designed to get mentally ill prisoners back to state-deemed competency and their jail time diverted to private outside mental health care agencies.

Rhodes, who is Republican, says his months-old approach relies on an intact Affordable Care Act, and that cutting subsidies would create a chain reaction resulting in private mental health agencies dipping back into the red and in many cases cutting services. “Ideologically, it’s a controversial issue,” Rhodes says of Obamacare. “But for us in law enforcement it really comes down to common sense. What kind of services are available for people who are mentally ill? It wasn’t as if by not allowing them to have coverage those people went away.”

Laura Norman of the West Yavapai Guidance Clinic, a 16-bed operation which takes many of Rhodes’s released prisoners, says the local mental health community will be watching the SCOTUS decision closely. “We actually have a very good idea of what will happen, because we’ve seen it before,” says Norman. “People who don’t need to be in jail will be in jail. Psychiatric issues will go unaddressed. People who don’t need to go to the ER will be in the ER. There are many people who are functioning extremely well in our community who will no longer be able to do that.” At the moment, Arizona receives $145 million in active grants through the ACA, part of which goes to funding clinicians in rural areas.

The only hospital within 90 miles of Prescott, and the county’s biggest employer, is the not-for-profit Yavapai Regional Medical Center West. Its Republican CEO, John Amos, is a buff former physical therapist who worked his way up the hospital’s ranks to his top position. Like the other hospital chiefs represented by the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association, Amos lobbied for the passage of Medicaid expansion. Amos told Pierce, in convincing him of the importance of the expansion, that in the two years after childless adults were disqualified from Arizona’s Medicaid program in July 2011, uncompensated care at the hospital—the all-important rate of bills that aren’t getting paid—had rocketed from 3.5 percent to 8.5 percent. Without enough patients on private health care plans and revenue plummeting, the hospital had to cut more than 100 fulltime positions. Pierce says Amos was concerned that he might have to close the maternity ward and the cardiac unit.

Only 13 other Republican lawmakers in Arizona—nine state representatives and four senators—joined Pierce in voting for Brewer’s plan to expand Medicaid. But the numbers have been favorable to Pierce. Amos, the CEO of the local hospital, says that uncompensated care has dipped back to around 3.5 percent, close to what it was in 2011 before the Arizona legislature pushed childless adults off of Medicaid. No longer are there threats of closing medical wards.

And then there’s this figure: 98.38 percent, Pierce’s take of the vote in 2014, his most recent bid for re-election, when rival Republicans couldn’t find anybody to run against him.

Pierce will be term-limited out of the senate next year, his eighth, and has no plans to continue his political career by jumping to Arizona’s House of Representatives, mostly because he’s weary of battling the right wing fringe: “There’s twice as many crazy people in the House.”

Given the political costs, it doesn’t surprise me that Pierce and Brewer are the only Republican politicians in favor of Arizona’s Medicaid expansion—and by proxy, Obamacare—who agree to speak to me, even after I repeatedly email and call every state rep and senator who voted for it. But it is the evasive nature of their constituents, those everyday Republican Arizonans who have signed up for private insurance through the ACA, that really catches me off guard. Simple math suggests there are a good number of them: In 2012, just over 100,000 citizens of Yavapai County voted in the presidential election, with more than 64,000 of those opting for Romney. In the same county, 8,846 people signed up for the ACA at the last open enrollment.

I came to Arizona wanting to know: Who were these people, and how did they feel about the prospect of their newly affordable health care being wiped away with a Supreme Court decision?

But these are not the sort of people who write letters to the editors of their local newspapers. I know because I scoured back issues of Prescott’s The Daily Courier, where letters from the populace included one titled “Obamacare lies are Hitler-esque” but none from self-identifying Republicans expressing their first-hand experiences with the program. And these are not the sort of people who reach out to organizations like Families USA, which is building a story bank of Americans in danger of losing their ACA subsidies.

“If I did, I wouldn’t tell you,” Rhodes tells me when I ask him if he knows of any regular Republican Joes getting their coverage through Obamacare subsidies.

“It sounds like you have your work cut out for you,” writes Barry Denton, president of the Yavapai Republican Men’s Forum. “I personally do not know of any Republican that has signed up for the Affordable Care Act. I truly believe most try to avoid it.”

The owner of the best Indian restaurant in Prescott is also no help. I’m failed by the bartender at the town square saloon. The League of Women Voters of Central Yavapai County hangs up on me. The Highway 69 Republican Club, Republican Women of Prescott, Yavapai County Young Republicans, and a host of other such political groups—and non-political ones; I’m looking at you, Italian/American Social Club and Yavapai County Jeep Posse—ignore my overtures.

The social stigma inherent in having to rely on any public subsidy and, worse, doing so through the enemy camp of Obamacare is probably why I’m striking out, says Richard Dehnert, vice mayor of Yavapai’s town of Clarksdale and community relations coordinator for a local health clinic. “It’s not the sort of thing people want to talk about,” Dehnert says. He tells me he’ll reach out to a Republican doctor friend of his who, while between jobs, signed up his wife for the ACA so that she could get care for some pre-existing conditions. I never hear from them.

Phoenix-based insurance agent Steven Pettit, who bills himself as an “Obamacare expert,” says he doesn’t learn his clients’ political affiliations but that it’s not hard to tell. “Most people tend to be pretty excited to be getting covered,” Pettit says. “But a few seem to be doing it begrudgingly, like they’re almost upset to be signing up, and I’d guess those are the Republicans.”

Because of the Sasquatch-like elusiveness of these characters, and their talismanic political value, when a Republican does publicly acknowledge participating in—and even appreciating—Obamacare, it tends to go viral quickly. Butch Matthews of Little Rock got his taste of Internet fame after telling ThinkProgress in 2013 that he was ecstatic with the $13,000 he was saving per year through the Affordable Care Act. Self-proclaimed “Tea Party Patriot” James Webb got heaps of attention when he made the unverifiable claim that he was voting for Hillary Clinton because he loves his Obacamare plan. Then there was the factually-porous ordeal of Luis Lang, a South Carolina Republican who the Charlotte Observer reported had refused to sign up for Obamacare but then repented after he was stricken with an affliction which threatened to make him blind. By then, the sign-up period was over, and he reportedly blamed the president for making the coverage too complicated.

When I recently asked Lang about the viral article he said that he never mentioned Obama during an hour-and-a-half interview with the Observer, and is only a registered Republican because “you gotta pick something.” “The last president I did vote for, believe it or not,” he added, “was Clinton.”

Ironically, the one Republican I meet in Arizona who admits to even considering signing up for a plan through the federal ACA exchange is the same one who just recently complained of “a dictator in Washington who tells us how to do our health care.”

It’s 105 degrees, and Arizona’s special strand of conservative politics has been in full weird desert bloom during my visit in late May. On the second day, gun-toting “free speech” protesters announce a plan to meet at a Denny’s in Phoenix before descending on a local mosque to draw pictures of Muhammad. (The Denny’s, in a plot twist, closes to thwart them.)

Across town in a Mexican restaurant, Richard Mack is explaining to me that he just flew in from Houston, where he was stumping for office on behalf of Carl Pittman, a member of the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, which Mack founded.

“Here’s another thing about him,” Mack says of sheriff candidate Pittman. “He’s black. That dispels another rumor about me: that I’m racist.”

Mack, a former sheriff of Graham County and a human bullhorn against Obamacare, commands attention like a stern step-dad. Deeply tanned, he wears his thick head of hair slicked back and is sporting an Arizona State Sun Devils shirt. He totes a large computer bag from which he pulls a seemingly bottomless supply of reading materials, including a booklet detailing his lawsuit which successfully challenged a provision of the Clinton-era gun control Brady Bill before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1996.

Mack has recently achieved a new fame of the sort that he hasn’t approached since then. That’s because Mack’s son started an online crowdfunding page to raise money for medical bills after his parents both suffered health crises.

Liberals lapped up the irony that Mack had blasted the idea of health coverage for those in need and then was left uncovered himself. Conservatives admired his principled refusal to sign up despite grave personal peril to himself and his wife.

Since the GoFundMe page first went up six months ago, Mack has received $45,489, some of which he says he has already started to spend. No small amount of that bounty was donated by people who use the page to criticize his decision not to sign up for Obamacare.

“We have raised—and this is a guestimate—$15,000 from liberals wanting to tell us to go to hell,” says Mack.

The family portrait on Mack’s GoFundMe page

Richard Ivan Mack’s saga of social enlightenment and financial malaise began with a tenure at the Provo Police Department in Utah, where he spent most of 1982 as an undercover cop driving a taxicab and attempting to worm his way into illegal activities. (A Supreme Court of Utah decision which reversed a drug dealing conviction he secured describes Mack hounding the suspect for psychedelic mushrooms multiple times, even knocking on the suspect’s door during a birthday party for his young son, before the target finally relented and arranged for him to purchase $40 of marijuana.)

Mack was a Graham County sheriff from 1989 to 1997, when he lost in an election. The subsequent jobs he tells me about were diverse: customer service for a health systems company, teacher at a juvenile detention center, used car salesman. He declared bankruptcy in 2004. Mack’s luck began to change in 2009 when he self-published a 50-page booklet called The County Sheriff: America’s Last Hope, which he claims was a runaway hit. He started getting so many speaking requests —he charged $500 at first; now he bills $3,000—that he quit his job, giving up his health benefits despite having suffered a minor heart attack during his car dealership days, in order to hit the circuit and write books full-time.

In January, Mack survived a massive heart attack while working out on a treadmill at the gym. The medical bills from that emergency were compounded by the fact that a month earlier, his wife, who suffered from arthritis, had been in the hospital with a severe MRSA infection.

“I’ve always put money away for our hospital bills, but not $130,000,” Mack tells me incredulously.

Mack believes that the “founding fathers were against the establishment of a welfare state” and that the Constitution they wrote does not allow Congress to provide national health care to Americans.

“‘Well, we helped 50 million people,’” Mack mimics in a do-gooder voice, then rebuts himself: “Does that make it constitutional?”

The way Mack tells it, the answer is no, and that is all that matters—until about three-quarters of his way through his bean and cheese tostada. That’s when he tells me that he and his wife considered signing up for the ACA many times after she was hospitalized.

“We both have talked about, ‘Yeah, maybe we should just sign up,’” Mack says. “We’re in such hot water here, you know. But this was after we had this [infection], so it wouldn’t have paid for her MRSA hospital stay. Hers was only about $30,000 so I thought, ‘Well, we’ll work it out, pay that one off.’ But then I had a heart attack, and then we couldn’t do it anyway.” The massive emergency room bills seemed to make signing up for future coverage pointless.

Perhaps more notable is Mack’s casual admission that he currently has health care coverage. He received it recently as part of his impending employment at the Phoenix-area private school Heritage Academy, where he will be teaching American History starting in August.

Mack can sleep better with this arrangement. “Getting insurance through a job is fine with me,” says Mack. “Going to the government website and saying, ‘Yes, I want to do this because it’s such a wonderful program’—I don’t believe that.”

Correction: In King v. Burwell, the Supreme Court is interpreting the Affordable Care Act, not deciding its constitutionality, as this piece originally stated.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, with support from The Puffin Foundation.

Gus Garcia-Roberts is an investigative reporter at Newsday and co-author of Blood Sport: A-Rod and the Quest to End Baseball’s Steroid Era.