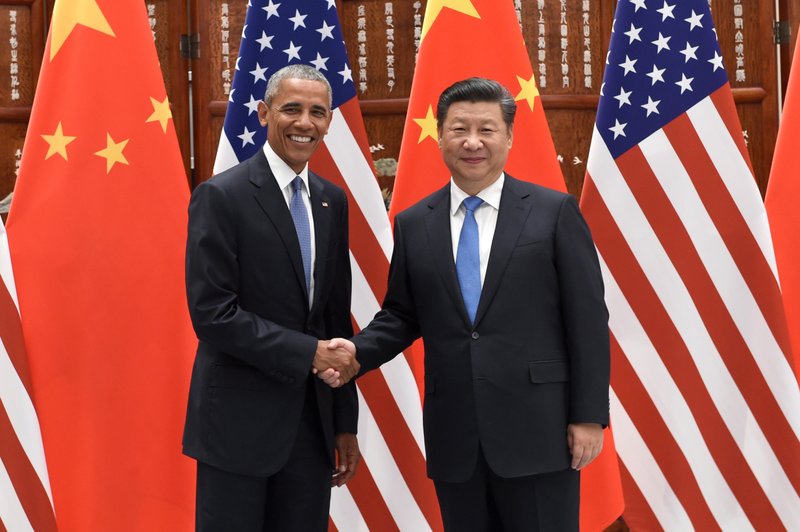

HANGZHOU, China (AP) — Setting aside their cyber and maritime disputes, President Barack Obama and China’s President Xi Jinping on Saturday sealed their nations’ participation in last year’s Paris climate change agreement. They hailed their new era of climate cooperation as the best chance for saving the planet.

At a ceremony on the sidelines of a global economic summit, Obama and Xi, representing the world’s two biggest carbon emitters, delivered a series of documents to U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. The papers certified the U.S. and China have taken the necessary steps to join the Paris accord that set nation-by-nation targets for cutting carbon emissions.

“This is not a fight that any one country, no matter how powerful, can take alone,” Obama said of the pact. “Some day we may see this as the moment that we finally decided to save our planet.”

Xi, speaking through a translator, said he hoped other countries would follow suit and advance new technologies to help them meet their targets. “When the old path no longer takes us far, we should turn to innovation,” he said.

The formal U.S.-Chinese announcement means the accord could enter force by the end of the year, a faster than anticipated timeline. Fifty-five nations must join for the agreement to take effect. The nations that have joined must also produce at least 55 percent of global emissions.

Together, the U.S. and China produce 38 percent of the world’s man-made carbon dioxide emissions.

The White House has attributed the accelerated pace to an unlikely partnership between Washington and Beijing. To build momentum for a deal, they set a 2030 deadline for China’s emissions to stop rising and announced their “shared conviction that climate change is one of the greatest threats facing humanity.” The U.S. has pledged to cut its emissions by at least 26 percent over the next 15 years, compared to 2005 levels.

The meeting of the minds on climate change, however, hasn’t smoothed the path for other areas of tension. The U.S. has criticized China over cyberhacking and human rights and voiced increased exasperation with Beijing’s growing assertiveness in key waterways in the region. Most recently, the U.S. has urged China to accept an international arbitration panel’s ruling that sided with the Philippines in a dispute over claims in the South ChinaSea.

China views the South China Sea as an integral part of its national territory. The U.S. doesn’t take positions in the various disputes between China and its Asian neighbors, but is concerned about freedom of navigation and wants conflicts resolved peacefully and lawfully.

Meeting Xi after the climate announcement, Obama said thornier matters would be discussed. He specifically cited maritime disputes, cybersecurity and human rights concerns, though the president didn’t elaborate or stress the topics during brief remarks in front of reporters at the start of the meeting.

The ceremony opened what is likely Obama’s valedictory tour in Asia. The president stepped off Air Force One onto a red carpet, where an honor guard dressed in white and carrying bayonets lined his path. A girl presented Obama with flowers and he shook hands with officials before entering his motorcade.

But the welcome didn’t go entirely smoothly. A Chinese official kept reporters and some top White House aides away from the president, prompting a U.S. official to intervene. The Chinese official then yelled: “This is our country. This is our airport.”

Throughout his tenure, Obama has sought to check China’s influence in Asia by shifting U.S. military resources and diplomatic attention from the Middle East. The results have been mixed.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership, a massive trade deal the White House calls a cornerstone of the policy, is stuck in Congress. Obama planned to use the trip to make the case for approval of the deal before he leaves office in January.

Climate represents a more certain piece of his legacy.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required to set national targets for reducing or reining in their greenhouse gas emissions. Those targets aren’t legally binding, but countries must report on their progress and update their targets every five years.

The state-run Xinhua News Agency reported Saturday that China’s legislature had voted to formally enter the agreement. In the U.S., no Senate ratification is required because the agreement is not considered a formal treaty.

Li Shuo, Greenpeace’s senior climate policy adviser, called Saturday’s declarations “a very important next step.”

If the deal clears the final hurdles, he said, “we’ll have a truly global climate agreement that will bind the two biggest emitters in the world.”

__

Louise Watt contributed to this report.

Copyright 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.