BOSTON (AP) — Elizabeth Warren has spent much of the last decade as a leader of the Democratic Party’s liberal wing.

But three and a half months into her presidential campaign, the Massachusetts senator is facing tough questions about fundraising and electability, along with lingering skepticism about her past claim to Native American identity. The longtime liberal superstar is embracing an uncomfortable role in the crowded 2020 contest: the underdog.

“This is the race I want to run,” Warren insisted in an interview with The Associated Press.

With the 69-year-old Democrat in the middle of the pack in early polling, her Boston-based senior advisers are implementing an aggressive — if risky — strategy that calls on Warren to forgo traditional high-dollar fundraising events and devote the saved time to interactions with rank-and-file voters. Advisers say she’ll also focus on seizing opportunities to stake bold new policy positions in real time, as she did recently by calling for the breakup of big technology companies like Amazon, which allow her to shape the debate and showcase her policy bona fides.

Her success or failure will help determine the direction of the Democratic Party in 2020 and, more specifically, whether Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders can maintain his early place at the head of the presidential primary pack. While Warren has sometimes sought to distinguish herself from Sanders, describing herself as a capitalist while Sanders runs as a democratic socialist, the New England senators appeal to the same progressive, populist wing of their party that is an increasingly dominant force in the age of President Donald Trump.

So far, Sanders has bested Warren in the few objective measures that exist: fundraising and polling. And while the first votes won’t be cast for another 10 months or so, former Warren allies in her neighboring state of New Hampshire, which holds the nation’s first primary, see cause for concern.

“I just don’t know if she would go over nationally,” said former New Hampshire state Rep. Daniel Hansberry, who was among 27 current and former state lawmakers who signed a 2015 letter urging Warren to seek the presidency. “In the Northeast and on the West Coast I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if she got a huge vote. But I don’t know if she’s too progressive for other parts of the country.”

Another signatory, former New Hampshire state Rep. Frank Heffron, said he’d be satisfied if Warren ultimately won the election, but said “it’s very unlikely” he’ll support her in the primary.

New Hampshire voter Kerry Query, a 54-year-old administrative assistant who voted for Hillary Clinton over Sanders in the 2016 primary, said she’s undecided this year but prefers Sanders over Warren so far.

“I don’t think she could get enough people behind her,” Query said. “If she got elected in the primary, there’s no way she could win.”

No one has an easy path to the Democratic presidential nomination, but few who expected to be in the top tier opened their campaigns with the same kind of stumbles as Warren.

Laying the groundwork for her 2020 run, Warren released the results of a DNA test in October that showed “strong evidence” of Native American ancestry, albeit at least six generations back. The move backfired, emboldening her critics — especially Trump, who regularly calls Warren “Pocahontas” — who have long charged that Warren exaggerated her ethnic heritage for personal gain.

Warren privately apologized to the head of the Cherokee Nation in early February. But just a few days later, reports surfaced that Warren had claimed Native American heritage on a 1986 Texas State Bar registration form.

“A large swath of the American people were introduced to her through what I like to call the DNA debacle,” said Democratic strategist Symone Sanders, who worked for Bernie Sanders during part of his 2016 campaign. She lauded Warren’s early campaign for having “meat on the bones” that rivals lack but warned that the Native American issue would continue to be a challenge.

Warren allies also acknowledge her early fundraising, a strength in her Senate campaigns, has been lackluster as a presidential candidate.

A federal filing reveals that she raised at least $300,000 on the day she launched her campaign. While not a complete picture, Sanders raised nearly $6 million the first day he was in the race and California Sen. Kamala Harris raised $1.5 million.

In the AP interview, Warren cast her fundraising challenges, including her move to eschew all high-dollar fundraising events, as a positive.

“I know that the way I’ve decided to run my campaign means that I’m leaving millions of dollars on the table,” she said.

“This is a chance to help repair our democracy. It shouldn’t just be about going out and raising a bunch of money and coming back and doing a bunch of TV ads,” she continued. “This is about meeting people in person. Talking with them about the things that touch their lives every day, about their hopes to make this country work not just for the rich and the powerful, but to make it work for them.”

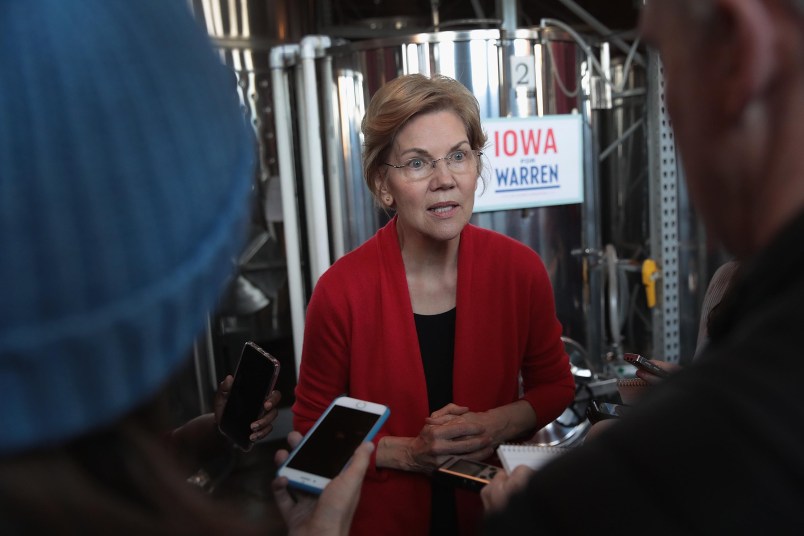

Warren is plowing ahead with an energetic approach designed to win over primary voters one event at a time.

She has made a significant time and organizational investment in the first four states on the presidential primary calendar — Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina. She has hired 65 campaign staffers for the first four states already, a number expected to grow in the coming weeks.

She’s also courting voters in other regions, launching a Southern tour on Sunday with stops in Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama. In all, she held 33 events across 11 states and Puerto Rico since launching on Dec. 31. Twenty-six of those events were in the early voting states, including 11 separate town halls or house parties in Iowa and 10 in New Hampshire, according to her campaign.

“There used to be an old adage back in the days when I was managing New Hampshire. It was ‘organize, organize, organize’ and get hot at the end,” said Democratic operative Mark Longabaugh, who previously worked for Sanders. “So I think they’re pursuing a version of that strategy with the modern communications techniques that we have now.”

Warren is hardly the only 2020 contender showering time and attention on key states.

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker has strong teams on the ground in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina. Others, such as Harris, are in the process of strengthening their early-state presence. And both Sanders and newcomer Beto O’Rourke are expected to aggressively court early-state voters.

Warren backers like Massachusetts Rep. Joe Kennedy III argue that she has proven doubters wrong since she first challenged Massachusetts GOP Sen. Scott Brown in 2012.

“It’s a matter, candidly, of the fact that we’re almost a year away from the election,” Kennedy said, “much like in Sen. Warren’s first race where there was a bunch of hand-wringing and bunch of concerns about whether she was going to be up for the task of taking on a very popular Republican incumbent.”

Kennedy continued: “I kept telling people: ‘Just wait. Wait and watch.'”