The dubious way that the Trump campaign is collecting “evidence” to support its post-election litigation was exposed in a Thursday hearing in its “SharpieGate” lawsuit in Arizona.

Before getting into the meat of the dispute, a judge said he was tossing out some of the declarations the campaign had submitted with the lawsuit, which echoes conspiracy theories on the far right about how election workers were handling certain ballots.

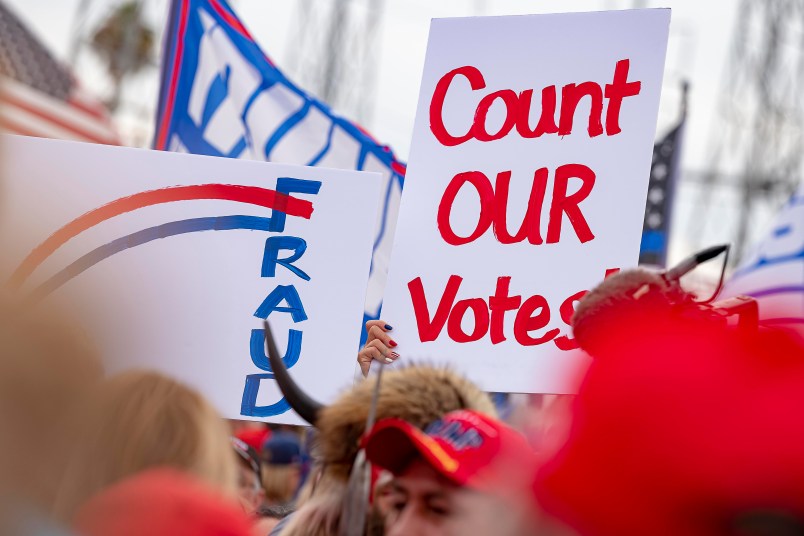

The case is one of several that President Trump’s campaign and its allies have brought to baselessly sow doubt about the outcome of the election and to stave off the final certification of Trump’s defeat. This particular lawsuit bootstraps onto a conspiracy theory known as “SharpieGate” that caught fire on the internet’s far-right corners during the week of the election. Pro-Trump social media groups circulated false claims that ballots filled out by Sharpie were not being read by Maricopa County’s ballot-scanners. Several high profile people in Trump’s inner circle amplified the claims. Already, a group of conservative activists brought a similar lawsuit that they since dismissed after the theory had been widely debunked by election officials.

Thursday’s hearing was the latest example of how those claims fall apart once they make contact with the legal system. Even as the Trump campaign lawsuit avoids some of the more bizarre aspects of the “SharpieGate” conspiracy theory, the lawsuit alleges that some voters may have been disenfranchised by how election workers in Maricopa County were handling issues arising from how the tabulators were scanning in ballots.

At the hearing, the Trump campaign’s lawyer Kory Langhofer stressed that they were not claiming any “fraud” occurred — a contrast to the rhetoric President Trump and his allies have employed. He said that the case concerned “good faith errors in operating machine[s].”

“It is not a fraud case, it is not a ‘stealing the election’ case,” Langhofer said. “This is, compared to that, a relatively boring and anodyne case about the proper procedures being followed.”

(The initial iteration of the SharpieGate theory that went viral last week alleged that elections officials had intentionally handed voters Sharpies to effectively nullify their ballots.)

Regardless, the number of votes that are implicated by the Trump campaign’s claims — which zero in on ballots marked as having an “over vote,” or more than one selection for President — are very small. Only 180 ballots cast in Maricopa County have been identified as presidential over votes, according to election officials, which is well short of the 12,000-vote margin Biden currently claims over Trump in Arizona.

Before the judge got into the merits of the dispute, he grilled the Trump campaign on the major problems in how it was collecting affidavits from voters who supposedly witnessed the tabulator issues.

In arguing that the affidavits — which were submitted via an online form — should be included, the Trump campaign’s attorney pointed to the CAPTCHA tool they used to filter out bots. He also said that the campaign excluded affidavits that were obviously spam, as well as those where the declarant didn’t match Maricopa County’s list of people who voted in-person on Election Day. (The lawsuit’s allegations concern those specific voters.)

The judge said that the campaign’s own admission that many people submitted apparently untruthful declarations, supposedly under penalty of perjury, showed that the way the campaign was collecting that evidence wasn’t in fact reliable.

“The fact that your process for obtaining these affidavits yielded affidavits that you yourself found to be false does not support a finding that this process generates reliable evidence,” Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Daniel Kiley said. “This is concerning.”

As he considered whether to toss out the affidavits in question, Judge Kiley showed increasing skepticism towards how the campaign collected its evidence and what that campaign’s own vetting of that evidence showed about its reliability.

“So, some of the affidavits that your solicitation received were from people that you can prove were not in fact voters on Election Day,” Kiley said. “You can prove that those affidavits are in fact false?”

The Trump campaign insisted that those affidavits weren’t necessarily false — maybe they were filed by people who watched their spouses vote that day and observed the tabulator issues — but acknowledged that they had them filtered out of the batch they filed in court nonetheless. Langhofer also admitted that they filtered out those declarants who were deemed obviously fake, because they used a fictitious name or profanity in their email addresses.

“To clarify … your solicitation of witnesses yielded some affidavits from people — sworn affidavits — that you yourself determined are clearly false and ‘spam’ as you put it?” the judge said.

After the lawyer confirmed that characterization, the judge then pointed out that the affidavits the campaign did submit were ones that they merely could not prove to be false.

Langhofer tried to suggest that because the declarations were submitted under punishment perjury, they could be trusted. But then the judge pointed out that the ones the campaign itself deemed to be fake were submitted under that disclaimer as well.

“If your process for gathering declarations has yielded sworn statements under oath that your investigation has determined to be false, that doesn’t give me any reason to believe that your process is one that generates trustworthy affidavits,” Kiley said. “It simply generated affidavits that you can’t prove are not true. That’s not the same as being trustworthy.”