The argument to bar Donald Trump from the 2024 election based on a section of the 14th Amendment has officially entered the bloodstream of the Republican primary.

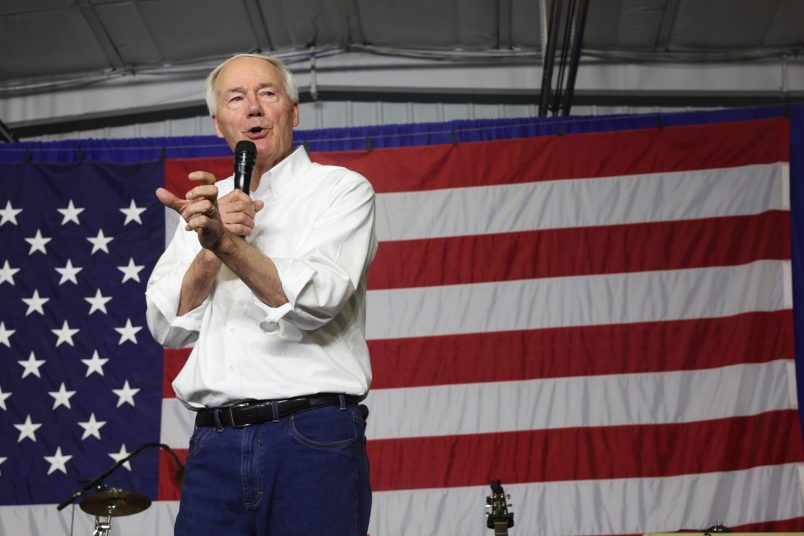

Former Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R) alluded to the theory Sunday on CNN.

“I’m not even sure he’s qualified to be the next president of the United States,” Hutchinson said of Trump. “And so you can’t be asking us to support somebody that’s not perhaps even qualified under our Constitution. And I’m referring to the 14th Amendment. A number of legal scholars said that he is disqualified because of his actions on January 6.”

That coterie of legal scholars got a buzzy boost when two conservatives made public a forthcoming law article they authored making an originalist argument that Trump’s behavior on and leading up to January 6, most recently detailed in the Georgia indictment, disqualifies him from serving again.

The argument hinges on Section Three of the 14th Amendment:

“No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof,” it reads.

This Reconstruction-era passage was included to block members of another insurrection from holding federal office again — namely, Confederates.

The two conservative scholars, William Baude of the University of Chicago and Michael Stokes Paulsen of the University of St. Thomas, are not the first to come up with this idea. It’s been percolating within good government groups for years, and some have tried to use its logic to bar legislators such as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and former Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-NC) from office. Those attempts were unsuccessful, though another challenge against a New Mexico county-level official succeeded in 2022.

Trump’s more central role in stoking January 6 — and his candidacy for office in 2024 — have prompted renewed attention from both left-leaning law scholars and resistance-oriented liberals still seeking that one weird trick to free themselves of the Trump threat.

Two good-government groups, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW) and Free Speech for People, are already crafting multi-state litigation strategies to challenge Trump’s candidacy under Section Three, according to the Washington Post. They’ve also written to state election officials, urging them to block Trump’s name from the ballot.

Per Baude and Paulsen, Section Three’s disqualification is self-executing — automatic, in other words, and not reliant on a court ruling to be upheld. But court action is all but inevitable. If a state election official heeds the groups’ calls and does indeed bar Trump from the ballot, such an action would almost certainly be immediately challenged, and likely fast-tracked up to the Supreme Court. Team Trump is preparing its oppositional legal strategies, including disputing that Trump actually engaged in the insurrection, per the same Post report.

The inevitable involvement of the high Court is usually where such liberal dreams go to die. Crooked Media’s Brian Beutler, though, argues that rubber stamping the Section Three argument and blocking Trump from the ballot would go an awfully long way in inoculating the Court from the reform that it opposes.

Calls for reform — from the mild approach of an ethics code to the Republican-head-exploding approach of expanding the bench — have gained steam as public approval of the Court plummeted in accordance with a series of high-profile wins delivered for the political right. Perhaps a canny operator like Chief Justice John Roberts, and whichever members of the majority he could coax to come along, wouldn’t mind a solution that both helps the Republican Party purge its Trumpian electoral baggage and gives the Court a claim to nonpartisan impartiality all at once, Beutler argues.

This theory would rely on many longshot moving pieces to work: a state official willing to risk the unmitigated wrath of Trump’s energetic and often well-armed base on the basis of an untested legal theory, a Supreme Court willing to buck the former President that appointed many of them and shares a worldview with even more, enough momentum to suppress the inherent discomfort in booting from the race the nominee that huge majorities of Republicans want to represent them.

And Asa Hutchinson, polling at a generous .7 percent in FiveThirtyEight’s aggregate, is not exactly the mouthpiece of his party.

Still, his bringing it up at least shows the theory’s legs, its ability to jump the gap from legal professor esoterica to “Meet the Press.”

It may still fail to materialize into anything less ephemeral than liberal wishcasting — but the bipartisan consensus that this theory is, at least, a legitimate one is growing by the day.