This story first appeared at ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Two weeks after the polls closed in this year’s Ohio primary, two U.S. Postal Service employees showed up in the office of Diane Noonan, the director of elections in Butler County. The workers carried a tray of 317 unopened ballots that had been sitting in a Postal Service warehouse since the day before the election.

The ballots would have counted if they had been delivered on time. Now, there was no way to legally count them. The next day, another ballot that had been postmarked in time to be counted arrived with no explanation. In Geauga County, officials found 26 such ballots; Lucas County saw 13.

Many election administrators in Ohio had already lost patience with the Postal Service. During Ohio’s April 28 primary, mail delivery had been so slow that the secretary of state publicly warned voters and called for the Postal Service to add staff. As they counted votes, Noonan and her team checked in with the service every day until the deadline. “We said, ‘Listen this is the last day,’” she recalled. “‘If we get ballots after this, they’re not going to be counted.’ They assured us.”

The Postal Service’s official excuse for misplacing the Butler County ballots was an “unintentional missort.” That response satisfied neither Ohio’s secretary of state nor Noonan. “We got an explanation that really wasn’t an explanation,” Noonan said. “It’s all in their hands. That’s what’s scary.”

The missing ballots in Ohio were just one sign of a larger problem. Frequently attacked by President Donald Trump and his supporters, the beleaguered Postal Service is under tremendous pressure to ensure that an unprecedented number of Americans can vote by mail in November, avoiding the potential health risk of in-person polling places during the coronavirus outbreak. The disarray Tuesday in the Georgia primary, in which voting machines malfunctioned and people waited in line for hours to cast their ballots, underscores the potential value of voting by mail.

With online retailers like Amazon cutting into its packaging revenue, the Postal Service has been losing both money and its former centrality in American culture. By running a national election smoothly, it could rebuff its critics and regain some of its prominence. But in the primaries, voters and election officials have been confronting the new reality of the Postal Service: delivery times slowed by years of budget cuts and plant closures. There have already been significant delays and mistakes in delivering ballots in Indiana, New Jersey, Maryland, Ohio, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C.

The Postal Service has not hit its own goals for on-time delivery of any type of first-class mail in five years. Last year, the agency delivered only 80.88% of its three- to five-day single-piece first-class mailings on time, missing its goal by 14.37 percentage points. Performance on that type of first-class mail — which is how some absentee ballots are sent — has been declining for the better part of a decade.

“In the last five years it’s gotten really bad,” said a former Postal Service executive, who requested anonymity because he still works in the mailing industry. He added that election officials still may not know enough about how the agency operates. “There’s a huge gap in understanding of how mail is sorted and how that could affect vote by mail ballots.”

Complicating the Postal Service’s task is that many states are building large vote by mail systems on the fly. In 2018, 26 states and Washington, D.C. had vote by mail rates under 10%, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. States that don’t regularly send ballots to voters may keep inaccurate voter address lists, leaving overburdened postal workers to deliver ballots to the wrong places.

Many states have failed to adjust their ballot deadlines to accommodate slower delivery. More than half of states allow voters to request an absentee ballot seven or fewer days before an election. Though some jurisdictions let voters submit ballots in designated drop-off boxes, those who wait too long to request or mail back their ballots could see their votes arrive too late to count.

There are other deadlines that can be affected by mail delivery problems. Many states use “received by” deadlines tied to when local election offices receive a ballot. This year, as mail delays have mounted, some states have had to extend these deadlines. Other states stipulate a date by which a mail ballot must be postmarked. Controversies over missing or illegible postmarks marred Wisconsin’s primary this year, and House Democrats tried to include national standards on ballot postmarking in one of the stimulus packages.

In the general election, even mail delays in line with the Postal Service’s historical performance could affect hundreds of thousands or perhaps millions of votes. According to a report from the Postal Service’s Office of Inspector General, 95.6% of election mail nationally was delivered on time during the 2018 election, just below the agency’s target of 96%. But the seven lowest-performing mail processing centers that the report examined, including facilities in swing states Florida, Ohio and Wisconsin, delivered an average of 84.2% of election mail on time. Six of those seven low-performing facilities failed to reassign staff to handle increased election mail volume.

To be sure, the Postal Service’s operations are still massive: Last year, the agency delivered a total of 143 billion pieces of mail. Election experts believe that the Postal Service has the capacity to handle a national election conducted primarily through the mail — but only if it coordinates closely with state election officials and if voters cooperate by sending their ballots early.

A Postal Service spokeswoman said in a statement that it employs “a robust and proven process to ensure proper handling of all Election Mail, including ballots. This includes close coordination and partnerships with election officials at the local, county, and state levels. As we anticipate that many voters may choose to use the mail to participate in the upcoming elections due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are conducting and will continue to proactively conduct outreach with state and local election officials and Secretaries of State so that they can make informed decisions and educate the public about what they can expect when using the mail to vote.”

She emphasized that most first-class mail “is delivered within 2-5 days, consistent with our delivery standards.”

Still, the USPS acknowledges that it needs more time to deliver ballots than is contemplated in election rules. “To account for delivery standards and to allow for contingencies (e.g., weather issues or unforeseen events), voters should mail their return ballots at least 1 week prior to the due date established by state law,” the USPS warned on May 29. “If a state law requires completed ballots to be received by election officials by a specified date (such as Election Day) in order to be counted, voters should be aware of the possibility that completed ballots mailed less than a week before that date may not, in fact, arrive by the state’s deadline.”

It’s unclear how many voters follow this advice or even know about it. “Any voter who thinks that they’re going to want to vote by mail should really be putting in their application as soon as possible and not leaving it up to chance,” said Tammy Patrick, a senior adviser to the Democracy Fund and a former Arizona election official.

For years, Patrick and other experts have warned election officials about the need to adjust operations and deadlines to account for a slower, more cash-strapped Postal Service. But these changes have been spotty, and some states and counties are simply not prepared.

Patrick has called for states to modernize vote by mail systems and implement best practices like intelligent bar codes on the outside of ballot envelopes for tracking them, which the Postal Service also recommends. “I’ve been saying that same thing for five years,” she said.

Eight days before Ohio’s primary, Sarita Montgomery, the Postal Service’s head of election mail for northern Ohio, sent election officials a frank warning about the state’s ballot deadlines, according to an email obtained by ProPublica. Ohio gave voters until noon on Saturday, April 25, three days before the election, to request an absentee ballot. Ballots had to be postmarked by April 27. Those rules, Montgomery suggested, meant that some voters could be disenfranchised. “There is a strong likelihood that the timing for mailing out ballots may not allow adequate time for voters to receive the ballot and return it by mail in time to meet the state’s postmark deadline,” she wrote.

The warning came as no surprise to Aaron Ockerman, executive director of the Ohio Association of Election Officials. Ockerman said his members reported “outrageous” mail delays during the primary, and his organization has been urging state officials for years to change ballot deadlines to allow for longer mail times.

“I have paraded this in front of just about anybody in the world who will listen, and said, ‘We have got to fix this,’” Ockerman said. “It’s just not fair to a voter to set this false expectation that if you wait until the last minute and request a ballot that you’re actually going to get it and legally be able to cast it under Ohio law.”

When the iconoclastic Cosmo Kramer tried to cancel his mail in a 1997 “Seinfeld” episode, his friend Newman, a postal worker, was scandalized but confessed: “All right, it’s true. Of course nobody needs mail.”

The joke rings hollow now as the Postal Service may be needed to deliver tens of millions of mail-in ballots despite being in turmoil on two fronts: politics and the pandemic. The Postal Service is a favorite target of Trump, who in April called the agency a “joke,” though he later tweeted that he would never let the Postal Service fail. By statute, the Postal Service is supposed to be an independent agency, with spending and operations overseen by its board of governors. With scant evidence, Trump has attacked vote by mail as “corrupt” and “fraudulent,” even as he and at least one member of his staff have voted by mail.

In April, the Postal Service alerted members of Congress that it could run out of money by September, requested a $75 billion bailout and projected a 30% decline in revenue because of the coronavirus outbreak. Trump has said that he won’t agree to a Postal Service bailout unless the agency raises prices for packages. The Postal Service has begun discussing a $10 billion loan from the Department of Treasury, the terms of which, The Washington Post reported, could give Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin unprecedented say over postal operations. It’s unclear if the Postal Service will still need the loan, because online shopping has picked up, although other revenue categories are down.

Last month, Louis DeJoy, a North Carolina businessman and longtime Republican donor who has given more than $1 million to Trump’s campaigns, was named postmaster general, stoking concerns that the agency was being politicized. DeJoy, who said upon his appointment that he looked forward to “working with the supporters of the Postal Service in Congress and the administration” to ensure that it remains “an integral part” of the federal government, did not respond to emailed questions.

Robert M. Duncan, chair of the board of governors and former chair of the Republican National Committee, said in a May 6 statement that the board “appreciated Louis’ depth of knowledge on the important issues facing the Postal Service and his desire to work with all of our stakeholders on preserving and protecting this essential institution.”

DeJoy’s appointment has coincided with departures of key administrators. Ronald Stroman, the deputy postmaster, and the lead coordinator on election mail, announced that he was resigning as of June 1. And David Williams, a Trump-appointed Democrat on the Postal Service’s board of governors, stepped down, reportedly angry with the Treasury Department for intervening in Postal Service affairs. Williams and Stroman did not respond to requests for comment.

Postal worker unions, for their part, say they’re sure that they can handle this year’s election mail, provided there’s proper planning and they are given enough staffing. Still, the pandemic has put a strain on many postal workers’ lives and on mail operations. More than 3,000 of the nation’s 600,000 postal workers have tested positive for COVID-19, 67 have died of the virus and 5,800 workers are under quarantine, according to the American Postal Workers Union. Even before the pandemic, the Postal Service relied on many postal workers regularly working overtime to get mail delivered.

Four workers in the union’s Detroit chapter have died of COVID-19. As mail volume has increased during the pandemic, local President Keith Combs said, his chapter has seen workers fall sick or miss work to care for loved ones. “The union office that I represent sits right in the middle of the worst ZIP code here in Detroit for the coronavirus. It has caused a big issue with the mail flow,” Combs said.

Detroit’s problems affected Ohio’s election mail delivery. Because of the wave of plant consolidation, mail for some northwestern Ohio municipalities, like Toledo, is sorted in Detroit. As Ohio’s mail delays mounted in the week before the primary, the secretary of state, Frank LaRose, a Republican, successfully lobbied to get mail sorted in-state.

John Dyce, president of the Ohio Association of Letter Carriers, worries that his organization’s reputation will be hurt by factors outside members’ control, such as election laws that don’t allow enough time for delivery. “We take great pride in what we do. We do feel we get unfairly blamed for it,” Dyce said. Years of cutbacks and a 2006 law requiring the Postal Service to prefund its retirement benefits, Dyce said, have put the agency in an untenable financial position: “Whenever you’re doing things like that, there’s the possibility for delays,” he said.

On April 8, one day after Wisconsin’s primary, a Postal Service official found 1,600 ballots headed for Appleton and Oshkosh in an area plant, according to a May report by the Wisconsin Election Commission. Those ballots never reached voters.

The report was critical of the Postal Service’s response: “Written inquiries to the USPS did not produce any specific information about these ballots,” the commission said. It said that its staff had been unable to learn any more, and that Wisconsin’s two U.S. senators have asked the Postal Service’s inspector general to investigate.

In Fox Point, Wisconsin, outside Milwaukee, election officials were baffled that ballots were mailed to voters only to be returned to the village by the Postal Service without an explanation. “People would ask us, ‘Where’s my ballot?’” said Scott Botcher, the village’s manager. “And I’d say, ‘Well, we mailed it.’”

Botcher’s office delivered the ballots by hand to the local post office each day. Still, 100 to 150 ballots per day were sent back to his offices in the week before the election. On Election Day, Fox Point village offices received a tray with 175 such ballots. It’s unclear how many Fox Point voters were disenfranchised, Botcher said, as residents who did not receive their ballots could still have voted in person.

He remains perplexed. “We still don’t know why it happened,” he said. “I just want to know so it doesn’t happen again and I can get my taxpayers their ballots.”

New Jersey held municipal elections on May 12 entirely by mail. There were reports of mail delays and problems in several cities including Paterson, where a City Council race was decided by just one vote. At least 300 ballots for the Paterson race, left in a mailbox in a nearby town, had to be discarded because of suspicions that they had been illegally bundled together. Mayor Andre Sayegh said that authorities are investigating possible ballot harvesting, which occurs when a political operative collects and submits large numbers of absentee ballots. New Jersey prohibits bundling by individuals of more than three ballots.

“Something nefarious has happened because I don’t know how anyone can explain 300 ballots appearing in a neighboring town,” Sayegh said.

Belleville, New Jersey, Mayor Michael Melham, a proponent of voting by mail, implored state officials to offer in-person voting options, to no avail. Belleville routinely sees problems with mail delivery, Melham said. “I’m a mayor,” he said. “Last November, I attempted to vote by mail and I never got my ballot.”

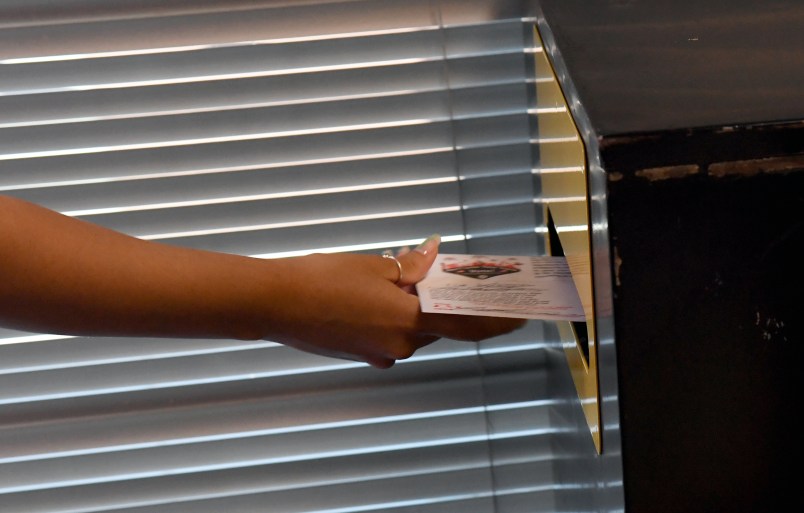

This year, Melham said, about a third of Belleville’s ballots came in after Election Night, but in time to count. Melham took to Twitter to point out a tub of ballots that the Postal Service had apparently left in the lobby of an apartment building. “The problems in the post office have been systemic for years,” Melham said. “I do think that they’re overwhelmed. I don’t think they’re capable any more of simply delivering mail. I just don’t think that they can do it.”

Ahead of Pennsylvania’s June 2 primary, Montgomery County election officials warned voters that “mail delivery times are slower than normal” and filed an emergency petition in a state court to extend the absentee ballot deadlines by one week. A judge denied the petition, but after Black Lives Matter protests gained steam across the country, and other counties asked for more time to process ballots, Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor, Tom Wolf, extended the deadline for receipt of ballots in Montgomery and five other counties.

In Maryland, state officials blamed a mailing vendor for ballot delivery problems and the vendor blamed the state. In Washington, D.C., election officials received so many complaints of missing ballots that officials allowed voters to send in ballots via email.

In Indiana’s Marion County, home to Indianapolis, it took two weeks for many voters to get their ballots in the mail ahead of the June 2 primary, according to the county clerk’s office. In a May 28 letter to Indiana’s secretary of state, Marion County Clerk Myla Eldridge warned that a flood of absentee ballots and mail delays could mean mass disenfranchisement: “In short, this could mean that thousands of ballots will remain uncounted despite the best efforts of both the Marion County Election Board and the voters themselves — even while state and county officials have strongly encouraged voters to vote by mail,” she wrote.

Russell Hollis, the office’s deputy director, said, “We are worried that if a voter puts a ballot in the mail, we won’t see it by Election Day.” Eldridge, a Democrat, asked the state’s Republican secretary of state to extend the deadline to receive ballots, but he was denied.

During the week of the election, the Marion County staff were still hearing from voters that they hadn’t received ballots. It took the office six days to count all of the absentee ballots, and the office is still certifying the results.

Election experts say that successful vote by mail systems depend on building good working relationships with the Postal Service. These relationships are reflected in a complicated system of logistics, communication and safeguards that can take years to set up. In states with large vote by mail operations — Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington run all-mail elections — the protections include last-minute election-night sweeps of Postal Service facilities to search for ballots.

Colorado election officials, working with a group of local and national mailing vendors, closely track ballot delivery times and take steps to move some mail faster. When deadlines get closer, vendors who help with ballot logistics will ask the Postal Service for clearance to send ballots using faster and more expensive classes of mail. “The whole system has to work together to increase the speed of the ballot,” said Judd Choate, Colorado’s director of elections.

On every election night since 2013, a lawyer and a staffer from Colorado’s election offices, along with a local Postal Service manager, have scoured the Denver General Mail Facility, which sorts 10 million pieces of mail per day. They arrive at 6 p.m., one hour before the state’s voting deadline. The team checks in with Postal Service managers who oversee various distribution points throughout the state to ensure all ballots are located. Any ballots that are found are hand-stamped, time-coded and then sent back to county election offices to be counted.

Similar sweeps are carried out at other postal facilities across the state. Colorado officials say the extra scrutiny works: In Colorado’s presidential primary this year, the Denver sweep found over 1,000 ballots that may not otherwise have been counted.

But many states and counties that don’t have large vote by mail systems have yet to implement these mail facility sweeps.

Choate said he’s not worried about the Postal Service’s ability to handle mail-in ballots this year. “We’ve had a number of conversations nationally, and we’ve also held meetings locally,” he said in late May. “I’ve been on the phone as recently as last week talking to local USPS officials, and I’ve asked the question straight out: Are you delayed in any way? They say that they’re not, and they have statistics to show it. That’s not a current worry that we have.”

Filed under: