The Supreme Court ruled Thursday to sustain the Voting Rights Act’s protection against attempts to dilute the voting power of racial minorities, dismissing Alabama’s attempt to create a standard that would make it nearly impossible to challenge such gerrymanders in the future.

It’s a massively significant, and very unexpected, victory for voting rights from a Court that has been hostile to them in recent years, and sustains one of the last remaining tools to fight racial gerrymanders. Part of the surprise stems from the fact that the right-wing majority let the map the Court knocked down Thursday be used in the 2022 midterms, despite a lower court finding it to be a near-certain illegal gerrymander.

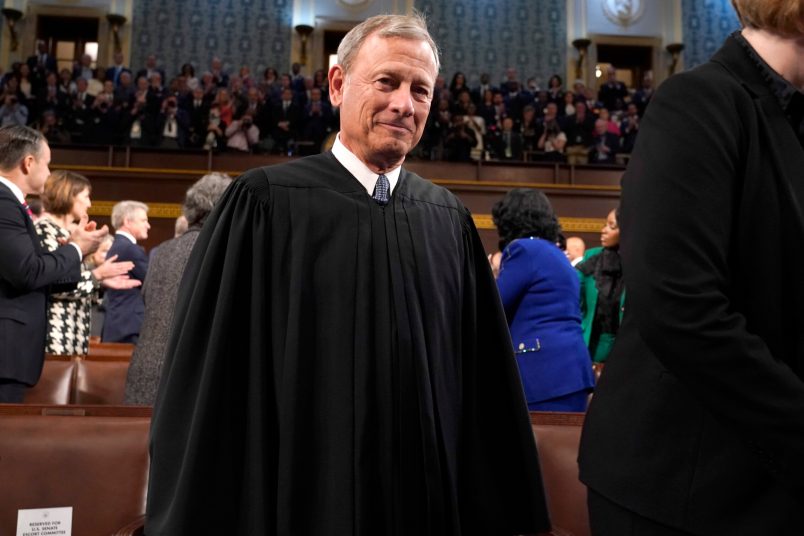

The decision was split many ways, but Chief Justice John Roberts delivered most of the majority opinion. The three liberal justices joined in the entire opinion, and Justice Brett Kavanaugh joined in most of it. Justices Clarence Thomas, Amy Coney Barrett, Neil Gorsuch and Samuel Alito all dissented to varying degrees.

The case was so significant because the Alabama challenge was centered on a novel idea.

To successfully bring a VRA vote dilution case — proving that the power of a voting group, in this case Black Alabamians, is being artificially weakened through district line drawing — litigants have to show, among other things, that the minority group is large and compact enough to constitute a majority in the district.

Alabama officials are arguing that that precondition itself is an illegal racial gerrymander — so any district with a majority-minority group would essentially only be possible if it was created by accident. Such a catch 22 would make it nearly impossible to bring these kinds of lawsuits under Section 2 of the VRA, one of the only pieces of the legendary civil rights law that the Supreme Court hasn’t yet totally decimated.

“The Court declines to remake its [Section] 2 jurisprudence in line with Alabama’s ‘race-neutral benchmark’ theory,” Roberts writes, referring to the VRA. He added that Alabama’s understanding of that section of the law “would require abandoning four decades of the Court’s [Section] 2 precedents.”

He adds later, in a zing, that the Court finds the new benchmark “compelling neither in theory nor in practice.”

Thomas, in his dissent, argues in favor of Alabama’s proposed standard, quoting a different case to call Thursday’s decision “‘yet another installment in the “disastrous misadventure” of this Court’s voting rights jurisprudence.’”

While the liberals, particularly Justice Elena Kagan, repeatedly raised the possibility that a novel approach of the sort sought by Alabama could result in a map with no majority-minority districts at all, Thomas applauds the idea of “screening out” attempts to “push racially proportional districting to the limits of what a State’s geography and demography make possible.”

Thomas argues that the factors used to determine illegal racial gerrymanders should be thrown out altogether, which would kill off one of the last remaining powers of the VRA. Alito also greenlights Alabama’s scheme in his separate dissent, but would keep the test factors.

In a footnote in the majority opinion, Roberts sneaks in a sly jab at Thomas.

“The principal dissent complains that ‘what the District Court did here is essentially no different from what many courts have done for decades under this Court’s superintendence,’” Roberts writes, quoting Thomas. “That is not such a bad definition of stare decisis.”

In his concurrence, Kavanaugh throws his right-wing peers a bone — something Thomas is quick to recognize in his own snarky footnote.

“Justice Kavanaugh, at least, recognizes that [Section] 2’s constitutional footing is problematic, for he agrees that ‘race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future,’” Thomas writes. “Nonetheless, Justice Kavanaugh votes to sustain a system of institutionalized racial discrimination in districting — under the aegis of a statute that applies nationwide and has no expiration date — and thus to prolong the ‘lasting harm to our society’ caused by the use of racial classifications in the allocation of political power.”

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on the case back in October. Kagan used the opportunity to trace the dismal history of the Roberts Court hobbling the Voting Rights Act; Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson tried an originalist argument in favor of the law, a twist on the omnipresent right-wing tactic.

The arguments came months after the Court sent shockwaves through the voting rights world when, in February 2022, it paused a lower court order that would have required Alabama to redraw its maps.

The lower court panel, consisting of mostly Donald Trump appointees, had found that Alabama’s maps likely violated Section 2 of the VRA. That surprise decision came after days of testimony and evidence, the rigor of which Kagan referenced as she bemoaned the Supreme Court majority’s decision to block its ruling. The contested map was used in the midterms soon after.

“That decision does a disservice to our own appellate processes, which serve both to constrain and to legitimate the Court’s authority,” she wrote in a 2022 dissent. “It does a disservice to the District Court, which meticulously applied this Court’s longstanding voting-rights precedent. And most of all, it does a disservice to Black Alabamians who under that precedent have had their electoral power diminished — in violation of a law this Court once knew to buttress all of American democracy.”

Roberts, with the other two liberals, also dissented from the order granting the stay. In the end, Kavanaugh switching to concur with Roberts and the liberals gave the VRA the win in Thursday’s 5-4 decision.

Read the opinion here: