Over the many months that Moore v. Harper, the independent state legislature case, unrolled, those guided by the paper trail the justices have left on the issue did not have much confidence that the radical theory would be rejected.

The independent state legislature theory (ISLT) reads two clauses of the Constitution extremely literally to find that only state legislatures have the power to administer federal elections — to the exclusion of state court authority, governors’ vetoes, rule-making by the secretary of state, voter-passed election initiatives, restraints from the state constitution and independent redistricting commissions. It would vest state legislatures with the enormous power to draw maps, pass election laws and cook up voter restrictions unchecked.

Experts worried particularly that the Court’s embrace of the theory would clear the way for a SCOTUS-sanctioned 2020 redux where red state legislatures could toss out lawfully chosen electors in favor of their own chosen slate.

At the time the Court agreed to hear a case dealing with the theory, at least three justices appeared to be enthusiastic fans of it: Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch. Justice Brett Kavanaugh had also displayed amenability to the idea.

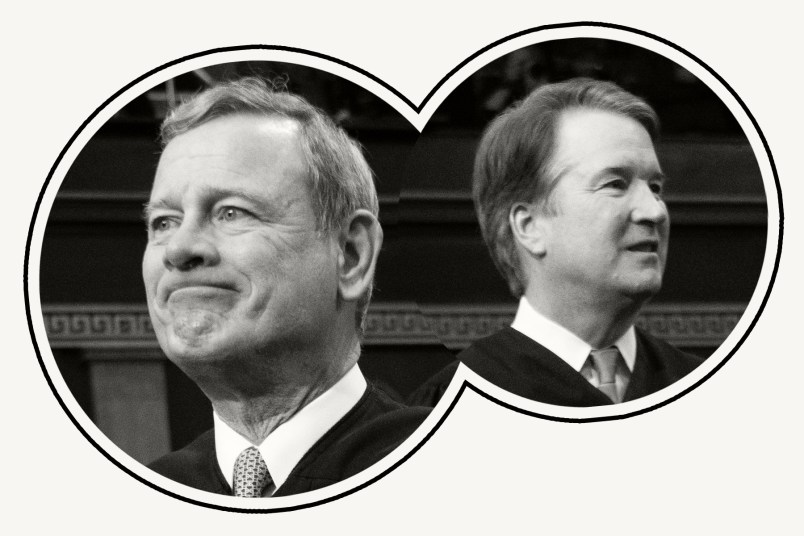

Chief Justice John Roberts came across as conflicted, seeming to embrace the theory in a 2015 redistricting case, but then allowing for the involvement of state courts, constitutions and laws in redistricting disputes about four years later.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett hadn’t written on the subject, though she expressed skepticism during the case’s oral arguments in December 2022.

As of Tuesday’s decision, Thomas and Gorsuch’s opinions remain mostly unchanged.

Thomas, writing for both in dissent, says: “In prescribing the times, places, and manner of congressional elections, ‘the lawmaking body or power of the state, as established by the state Constitution,’ performs ‘a federal function derived from the Federal Constitution,’ which thus ‘transcends any limitations sought to be imposed by the people of a State.’ As shown, each premise is easily supported and consistent with this Court’s precedents.”

In a footnote, he squarely addresses the electors scenario experts feared, asserting that “the state legislature’s power to direct the manner of appointing electors may not be limited by the state constitution.”

Interestingly, Alito does not join in the part of Thomas’ dissent that addresses the merits of the ISLT — he only joins the part discussing the case’s jurisdictional issues.

Still, it’s unlikely that Alito’s abstention represents a change of heart. It may just be an expression of his belief that the case is mooted, and that it’s not appropriate to write an opinion when there is no live “case or controversy” to address.

Back in March 2022, when he dissented from a stay at an earlier point of the case, he wrote that the North Carolina legislators advancing the theory would likely win on the merits.

“The Elections Clause provides that rules governing the ‘Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives’ must be ‘prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof,’” he wrote then, joined by Gorsuch and Thomas, adding: “Its language specifies a particular organ of a state government, and we must take that language seriously.”

Kavanaugh, who ultimately joined the majority Tuesday in rejecting the theory, had been a bit more cryptic than the other three in his past decisions, but still dragged behind him receipts suggesting that he was open to the theory.

He’d joined in a concurrence Gorsuch wrote in a Wisconsin 2020 election case, where Gorsuch said: “The Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

Kavanaugh also wrote separately, saying in a footnote that “As Chief Justice Rehnquist persuasively explained in Bush v. Gore … the text of the Constitution requires federal courts to ensure that state courts do not rewrite state election laws,” he wrote.

In his Tuesday concurrence, Kavanaugh still dwells on the question of federal court involvement in state election cases — which could presage an openness to Bush v. Gore clones in the future — but joins the majority opinion in full. In a clue to where he’d ultimately end up, he said during oral arguments that North Carolina legislators were going further than the 2000 concurring opinion by Rehnquist that he’d cited favorably.

Roberts, the author of the majority opinion rejecting ISLT, would have once been counted among its staunch supporters.

“An Arizona ballot initiative transferred that authority from ‘the Legislature’ to an ‘Independent Redistricting Commission,’” he wrote in 2015. “The majority approves this deliberate constitutional evasion by doing what the proponents of the Seventeenth Amendment dared not: revising ‘the Legislature’ to mean ‘the people.’ The Court’s position has no basis in the text, structure, or history of the Constitution, and it contradicts precedents from both Congress and this Court.”

But four years later, he was pointing to independent commissions as an advancement in states purging their redistricting processes of partisan sway.

“Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” he wrote of such cases — a total contradiction of the ISLT, which would bar all three of those entities from the redistricting process.

Ultimately, the combined opinions in Moore v. Harper spend much more time on the jurisdictional questions of the case than the merits of the theory.

Some have pointed out that the opinion stays vague on when state courts have gone “too far” afield from the bounds of judicial review — perhaps leaving the door open to a future Bush v. Gore. Even if that’s so, it’s more a retention of the status quo than a drastic new change.

Most importantly, the majority undoubtedly rejected the most radical and dangerous right-wing attempt yet to put federal elections in the hands of state legislatures, many of which, particularly in states that decide presidential elections (Wisconsin, North Carolina, etc.), have been so gerrymandered as to be much further to the right than the constituencies they represent.

“The Elections Clause does not vest exclusive and independent authority in state legislatures to set the rules regarding federal elections,” Roberts writes. And that’s that.