The Supreme Court Thursday struck down a New York gun law requiring that license applicants show “proper cause” to have a concealed weapon.

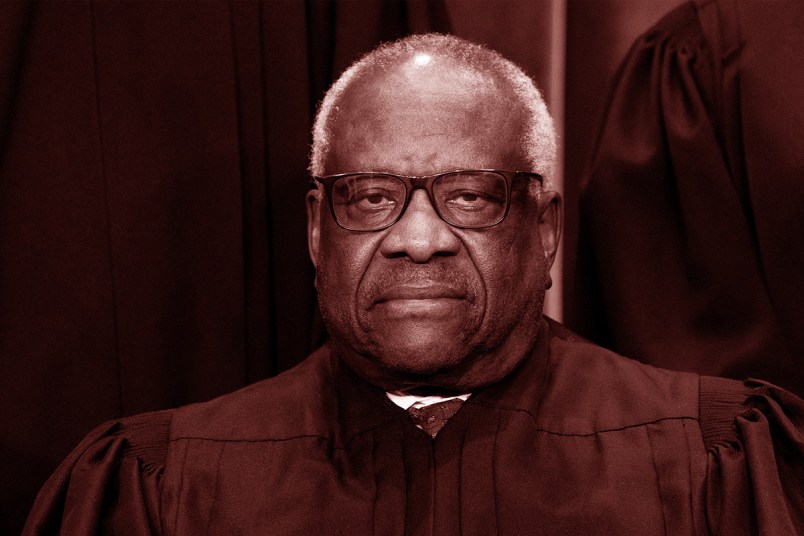

“New York’s proper-cause requirement violates the Fourteenth Amendment by preventing law-abiding citizens with ordinary self-defense needs from exercising their Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms in public for self-defense,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the majority.

Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito and Amy Coney Barrett wrote concurring decisions — Chief Justice John Roberts joined in Kavanaugh’s. The three liberal justices dissented.

“The exercise of other constitutional rights does not require individuals to demonstrate to government officers some special need,” Thomas wrote, echoing comments made by Roberts during oral argument. “The Second Amendment right to carry arms in public for self defense is no different.”

The way in which the decision is argued is nothing short of radical. Thomas writes that only regulations that echo those from near the country’s founding are legitimate, and that government interests — like the safety of its citizens — is not enough without a historical analogue.

“The government must affirmatively prove that its firearms regulation is part of the historical tradition that delimits the outer bounds of the right to keep and bear arms,” he writes.

Under that logic, it’s difficult to see many if not most gun regulations being held constitutional by this Court.

Breyer, in his often lofty and professorial dissent, sneaks in a jab at his conservative colleagues: “Most importantly, will the Court’s approach permit judges to reach the outcomes they prefer and then cloak those outcomes in the language of history?”

He, ever-politely, accuses his colleagues of cherry-picking from the historical record to find cases that suit their argument.

“At best, the numerous justifications that the Court finds for rejecting historical evidence give judges ample tools to pick their friends out of history’s crowd,” he writes. “At worst, they create a one-way ratchet that will disqualify virtually any ‘representative historical analogue’ and make it nearly impossible to sustain common-sense regulations necessary to our Nation’s safety and security.”

Justice Samuel Alito builds atop his comments at oral argument that New York is a dangerous cesspool, where law-abiding citizens need weapons to protect themselves. He also argues that the New York gun licensing law hasn’t stopped every mass shooting, so why bother?

“How does the dissent account for the fact that one of the mass shootings near the top of its list took place in Buffalo?” he ponders. “The New York law at issue in this case obviously did not stop that perpetrator.”

Kavanaugh, joined by Roberts, attempts to soothe the inflammatory rhetoric spewed by Thomas and Alito.

This ruling doesn’t apply to every gun licensing regime, the two argue — just ones like New York’s, that require a reason for a person to need a concealed weapon. That only seems to cover six states, though, as Breyer points out in his dissent, they include some of the densest population centers in the country, including Washington D.C., Los Angeles and Boston.

The gun regulation case is perhaps the most important the Court has heard since it ruled that people can keep handguns in their homes over a decade ago.

The decision takes on particular emotional resonance in the state shortly after a shooter killed 10 people in a Buffalo, New York grocery store. Most of the victims were Black, and the shooter allegedly left behind a race-based manifesto before live streaming the shooting.

The case specifically focuses on New York’s concealed carry permitting scheme. To get a license to carry a weapon, applicants must demonstrate “proper cause,” or a reason why they need a hidden firearm on their person. During oral arguments, the state gun rights advocacy group and sympathetic justices framed the requirement as an infringement on a constitutional right that would be ridiculous if applied to another.

“You don’t have to say, when you’re looking for a permit to speak on a street corner or whatever, that, you know, your speech is particularly important,” Roberts said. “So why do you have to show in this case, convince somebody, that you’re entitled to exercise your Second Amendment right?”

Still, the justices couldn’t help but drift to the clear implications of widening the ambit of New Yorkers allowed to carry concealed guns. While the individuals who’d been denied licenses and the gun advocacy group that backed them in challenging the law were from upstate New York, justices contemplated the impact their ruling would have in the densely-packed heart of New York City.

Roberts brought up a series of environments: sports stadiums, college campuses, bars. Justice Elena Kagan mentioned the subways.

New York City officials, girded for a pro-gun decision from the far-right Court, have been exploring their options.

“After what we saw the Supreme Court did on abortions, we should be very afraid. In a densely populated community like New York, this ruling could have a major impact on us,” Mayor Eric Adams said during a recent press conference. “We are now looking with our legal experts to see what we can do — how we would curtail the behavior, [in] our transit system, around our schools.”

During the arguments, the lawyer for the gun advocacy group was quick to say that a “sensitive place law” — regulations from the state about where guns are not permitted — is very different from the one New York has on the books now, which limits concealed carry licenses at the source. He seemed to be offering the justices the opportunity to allow a less stringent law as an offramp.

“The issue before us, as I understand it, is the permitting regime,” Kavanaugh said, taking the bait. “We don’t have to answer all the sensitive places questions in this case, some of which will be challenging, no doubt. Is that accurate?”

Read the opinion here: