As COVID-19 may be on a slow, downward trend in the hotspots of New York City, New Orleans, and Detroit, the virus appears to be finding new ground elsewhere: in rural America.

Data compiled by the Kaiser Family Foundation suggests that infection rates are increasing at higher rates in rural areas than in urban settings.

It’s a significant, if not unsurprising trend: the disease is fanning out from big, urban areas like New York City to more sparsely populated parts of the country.

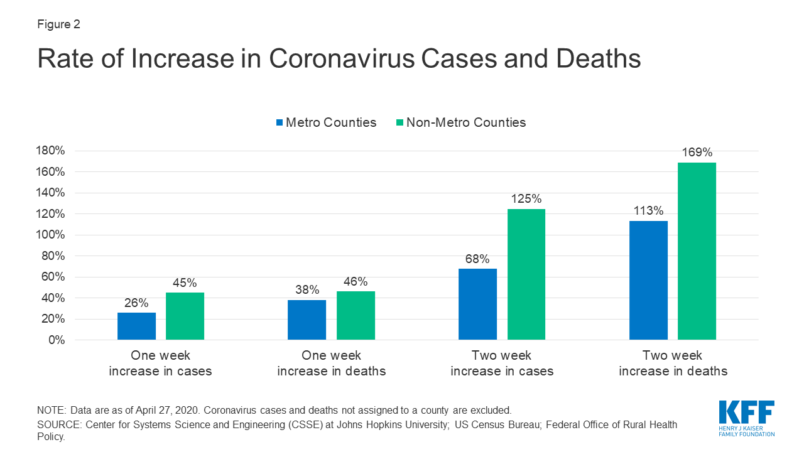

Researchers found that while urban areas continue to have higher death rates and more cases per capita, the growth rate of both metrics is now higher in rural America.

According to the study, between April 13 and April 27, the per capita rate of COVID-19 cases went from 51 cases per 100,000 people to 115 per 100,000 — a 125 percent increase.

The death rate rose commensurately, jumping 169 percent from 1.6 deaths per 100,000 people to 4.4 per 100,000.

Josh Michaud, Associate Director for Global Health Policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation and a former infectious disease epidemiologist with the Department of Defense, told TPM that COVID-19 appeared to be following a similar pattern to previous large-scale pandemics.

“It makes sense that it was urban areas that got hit earlier and hit faster, that’s where the disease was first, where the outbreaks were first seeded,” Michaud said. “And it takes time for that to spread to other geographic regions and because of the less dense geography in rural areas — that partially explains the time delay.”

Projections by the Centers for Disease Control leaked to the New York Times on Monday suggested that the federal government also expects COVID-19 to begin hitting rural areas harder than urban ones. Citing data from up to May 2, the document said that, over the coming months, cases in “the Great Lakes region, parts of the Southeast, Northeast, and around southern California” were expected to increase. (A White House spokesperson said that the leaked numbers were “not reflective of any of the modeling done by the task force or data that the task force has analyzed.)

Cynthia Cox, Vice President at the Kaiser Family Foundation and Director for the Program on the Affordable Care Act, told TPM that there was a chance the pandemic could worsen an already fragile health care situation in rural communities.

“Those are also the same areas that have fewer health care resources and have older populations, and even the younger population tend to be sicker,” Cox said. “So it’s possible that even if the virus continues to spread, this is a troubling sign because those areas could be harder hit.”

Rural America is uniquely vulnerable to the ravages of COVID-19. A decade-long crisis has led to scores of rural hospitals shutting down, with 126 closing since 2010. Forty-seven percent of rural hospitals in the U.S. were in the red in 2019, according to statistics from the Chartis Center for Rural Health.

The nature of the illness as well could wreak havoc on rural communities. America’s rural population is, on average, older and and has more preexisting conditions that make COVID-19 more dangerous.

Rural counties have far fewer intensive care unit beds per capita as well, limiting the amount of capacity they may have in the event of widespread outbreaks.

Michaud said that data showing how “concentrated outbreaks can be, even in rural counties,” surprised him.

“In rural areas, there’s a problem of meat processing plants and the prisons and institutional areas where we’re seeing such a rise in cases that has to do with the way their work is set up and the way conditions are and the lack of lockdown procedures that have occurred in some of these places,” he said.

Some of the same largely rural states that have had serious outbreaks — like North Dakota and Georgia — are at the forefront of the effort to open up, casting social distancing restrictions aside.

Cox noted an irony in that, saying that “some states are opening up despite the fact that the rural areas in those states have the highest rates of death and infection of coronavirus.”

Michaud cautioned that the data suggested that rural America was likely on the upward bound of a potentially steep infection curve.

“If we are asleep at the wheel a little bit and we don’t recognize that large-scale outbreaks can occur and will occur in rural counties that are especially vulnerable, we could find ourselves very rapidly in a situation where we’re looking at severe epidemics,” Michaud said. “In that case, it would’ve been premature to relax social distancing and expect that the cases would decline.”