The 2020 Census data dropped on Thursday, the starting gun of the redistricting process.

Of all the impending threats that Democrats hope to address with a set of democracy reform bills, the 2020 redistricting cycle is approaching the quickest. Congress is in recess, with the Senate not planning to come back to Washington D.C. until September 15.

By then, the process of drawing the next decade’s political maps will be well underway.

“Some states will pass maps in September — some may even before September,” Michael Li, senior counsel at NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, told TPM. “It depends on how fast they can get the data, but there are rumors that some states might try to move really, really fast.”

Recess isn’t the only obstacle to Senate Democrats passing the For the People Act, which encompasses a suite of redistricting reforms: A group of senators is currently working on a compromise bill, expected to be a whittled-down version of the original that can win the support of all 50 Democrats. While details of the coming bill are scant, the Democratic caucus has prioritized the provisions in the legislation aimed at combating partisan gerrymandering as critical.

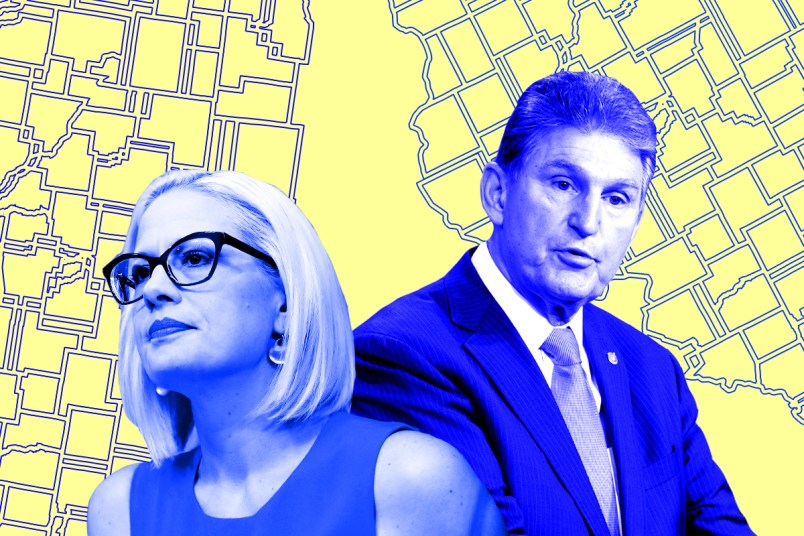

Then there’s the inescapable problem of the filibuster, which currently would give Republicans an easy veto of the compromise bill. Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) have opposed changing how the filibuster works, dismissing such reforms as a carveout that would allow pro-democracy legislation to pass with a simple majority.

If Democrats’ reforms are to have an impact on the 2020 redistricting cycle, senators have a lot of work to do — in very little time.

While experts told TPM that there is no true binary, no turning point where it’s too late to effectuate any gerrymandering reforms, things will only get messier and more difficult the more time Congress lets elapse.

Passed By Early Fall

Some reforms, such as one that would require independent, nonpartisan commissions to draw states’ maps, are already off the table for this cycle.

“For provisions included in the For the People Act about independent commissions, it’s too late,” Dave Daley, former editor in chief at Salon and an author of two books about gerrymandering, told TPM. “Commissions started collecting applications and seating members and holding public hearings months ago. The public and behind-closed-doors processes of redistricting have already gotten underway.”

Other reforms would still have an impact, but the window is closing. Those include, per Li, reforms that add transparency to the map-drawing process. The original For the People Act would nix any state legislative privileges that keep discussion and debate about map-drawing private.

In the past, some of that private discussion has revealed purposeful, racially discriminatory intent by the actors drawing the maps. “Smoking gun” emails from 2010, revealed during a protracted legal fight over Texas maps, showed Republican operatives maneuvering to dilute the voting power of Latinos. The For the People Act wouldn’t let legislators hide behind privilege to keep those conversations private.

“If they don’t pass reform by September or early October, a lot of states will have passed maps,” Li said. “That leaves transparency to the public off the table at least for this decade, and they may end up not being able to effectuate legislative privilege reforms.”

Still Time

The good news for democracy reformers is that provisions setting standards that maps must meet can arrive fairly late in the game, even after maps have been drawn, and still have an impact. The bad news is that litigation will be required to fight maps that don’t meet those standards.

Those standards in the For the People Act include establishing uniform rules that every state must follow when drawing their maps, with an emphasis on keeping towns and neighborhoods with shared identities and common interests together. It would also mandate protections for communities of color, the frequent target of partisan gerrymanders, if they have demonstrated a consistent ability to elect their preferred candidates. Maps would also be subject to a statistical test to ensure they don’t give one party an undue advantage statewide — if they fail the test, they must be redrawn.

But fighting bad maps in court can get messy, and time-intensive. If maps get struck down, state legislatures may have to hold additional sessions to redraw them. These kinds of court battles can stretch for years: even if a court ultimately strikes down the maps, there’s a risk that they’ll be left in place and used for elections while the litigation is still underway.

Those delays, Li pointed out, could stretch so far as to delay primary elections, creating a messy and confusing atmosphere for voters.

Another problem with fighting bad maps through litigation is the Supreme Court’s aversion to getting involved with the issue, repeatedly declaring map drawing to be a question of politics best left to the other branches of government.

“The Supreme Court is not gonna stand up to protect the right to vote and against gerrymandering,” Jana Morgan, director of the Declaration for American Democracy, told TPM. “The For the People Act is the best bet.”

A Turbocharged Redistricting Cycle

This is also the first redistricting cycle with a completely hobbled Voting Rights Act.

The Supreme Court tossed out the law’s formula for determining which states or localities had racially discriminatory voting practices and had to be “precleared” by the federal government before they changed their voting systems in 2013. A follow-up decision this year will have the practical result of making it more difficult for minority voters to challenge laws they feel discriminate against them.

“States knew there was a cop on the block,” Li said of redistricting under a fully-functioning VRA. “They tried to get away with things, but not as much as they would have otherwise.”

“Now the incentive is to be as aggressive as you can and dare the courts to strike maps down,” he added. “In the meantime, you may have gotten an election cycle or two or three on bad maps.”

That’s a problem the original For the People Act would help mitigate. It would shift the burdens away from those challenging the maps, and allow the U.S. Attorney General to intervene, bringing the might and resources of the federal government to uphold the Act’s provisions barring partisan gerrymandering.

But the further we get into the 2020 redistricting cycle, the less potency the reforms will have, Li said. He suggested that an early return from recess and passage after Labor Day would be optimal.

“The clock is ticking; there is still time to enact reforms in a meaningful way,” he said. “But the crisis is upon us and it’s better for everyone concerned if the rules are in place before states get far along in the redistricting process.”