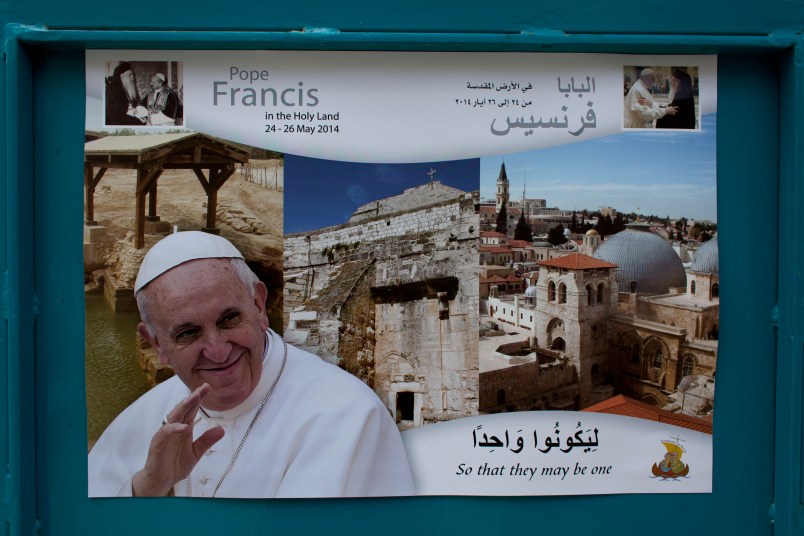

JERUSALEM (AP) — When Pope Francis sets foot in the Holy Land next week, he’ll be treading on diplomatic eggshells at virtually every stop.

Israeli-Palestinian politics are just one of the many sensitive issues Vatican officials are navigating. Other sore points are incidents of anti-Christian vandalism in Israel, lingering tensions between the Holy See and the Jewish community, historic disputes with rival Christian denominations and closed-door real estate negotiations with Israel.

“This is the Holy Land. It’s complicated,” said Hana Bendcowsky of the Jerusalem Center for Jewish-Christian Relations, an interfaith group.

Vandals in Israel have recently scribbled anti-Christian graffiti on several Christian holy sites and properties. Israel’s internal security agency says it fears there could be more such attacks, and local Vatican officials have urged Israel to safeguard Christian holy sites ahead of the pope’s visit.

The vandalism “poisons the atmosphere of coexistence” surrounding the pope’s visit, said Latin Patriarch Fouad Twal, the top Roman Catholic clergyman in the Holy Land.

Every stop on Francis’ itinerary carries symbolic weight and tiptoes around political sensitivities.

The pope will first spend half a day in Jordan on May 24, visiting the traditional site of Jesus’ baptism at the Jordan River, before arriving in the West Bank to meet Palestinian leaders and celebrate Mass in Bethlehem, near the traditional site of Jesus’ birth.

Instead of a quick 10-minute drive from Bethlehem to neighboring Jerusalem, the pope will fly by helicopter 28 miles (45 kilometers) to an official welcoming ceremony at Israel’s international Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv. He then flies back to Jerusalem to meet Israeli leaders and visit holy sites and Israel’s Holocaust memorial.

The zigzag takes into account Jerusalem’s disputed status. Israel claims the city as its undivided capital but its control of east Jerusalem, captured in 1967, is not internationally recognized. The Rev. David Neuhaus, a church official in Jerusalem, and an Israeli official said the airport welcome is standard protocol for visiting world leaders. The Israeli official spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to media about the preparations for pope’s visit.

Some of Francis’ planned stops could cause discomfort in Israel.

In Bethlehem, the Argentine pontiff will visit the Deheishe refugee camp, home to Palestinians who fled or were driven from their homes in the 1948 war surrounding the establishment of Israel. Palestinian officials are eager for Francis to see the impoverished camp and hear Palestinian grievances against Israel.

“The pope will see the reality,” said Xavier Abu Eid, a Palestinian official helping coordinate the papal visit.

Also, the pontiff will meet with the top Muslim cleric in Jerusalem, the grand mufti, at the Holy Land’s most politically sensitive religious site — the Old City compound revered by Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary and by Jews as the Temple Mount. The site witnesses frequent clashes between Israeli police and Muslim worshippers.

Only three other popes ever visited the Holy Land.

Pope Benedict XVI, who was briefly conscripted into the Hitler Youth during his childhood in Germany, drew a lukewarm response in his 2009 visit. Officials at the Holocaust memorial complained that his speech there glossed over the Nazi genocide.

Benedict’s predecessor, Pope John Paul II, received a warmer welcome during a landmark trip in 2000 that highlighted improved relations with Israel. John Paul had asked for forgiveness on several occasions for the wrongs inflicted by Christians on Jews.

Pope Paul VI, the first pope to come to Jerusalem, made history in 1964 when he met Patriarch Athenagoras, the then-spiritual leader of the world’s Greek Orthodox Christians, and the two hugged in a landmark embrace. The meeting ended 900 years of estrangement between the churches.

Francis’ visit — on the 50th anniversary of that historic embrace — aims to further relations between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches, Vatican officials say.

Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the spiritual leader of the world’s Orthodox Christians, will meet in Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which marks the traditional site of Jesus’ burial.

Representatives of other churches will also be present, including the first leader of Lebanon’s largest Christian sect, the Maronite Catholic Church, to visit Jerusalem since Israel captured the city’s eastern sector.

This has triggered anger in Lebanon, which bans its citizens from traveling to archenemy Israel. The leading Lebanese daily, As Safir, called the visit by Cardinal Bechara Rai “a historic sin.”

The militant Hezbollah group warned that Rai’s trip to Jerusalem could have “dangerous and negative repercussions.”

Irabhim Amin al-Sayyed, head of Hezbollah’s politburo, met with Rai on Friday to present his group’s reservations. Rai has defended his trip, which he described as a religious pilgrimage.

Tempers are also flaring over another stop on Francis’ tour, which is at the center of an Israel-Vatican dispute — the Room of the Last Supper, where Jesus was said to have had his final meal with his disciples before his crucifixion.

Ultra-Orthodox nationalist Jews have plastered Jerusalem with posters furiously claiming Israel will give the Vatican control there.

The room is located in a Crusader-era building that belonged to Franciscan friars in the 14th century but was transferred to Ottoman authorities in the 16th century and taken over by Israel in 1948. To complicate matters, the building’s ground floor is revered by Jews as the tomb of the biblical King David.

The Vatican has for years petitioned Israel for more Christian access. Israel generally prohibits celebrating Mass there and restricts Catholic prayers to twice a year, on Holy Thursday and Pentecost. It has refused greater access, wary of setting a precedent of relinquishing properties taken over in the 1948 war.

Still, it will let Francis hold Mass in the room, as it did with Benedict.

A senior Catholic official said the two sides were close to a deal allowing official daily liturgical prayer there, but not a transfer of control.

An Israeli official declined to discuss details, but said negotiators have reached agreement on most disputes involving church properties. Both officials spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to publicly discuss the negotiations.

___

Follow Daniel Estrin at twitter.com/danielestrin.

___

Associated Press writer Zeina Karam contributed to this report from Beirut, Lebanon.