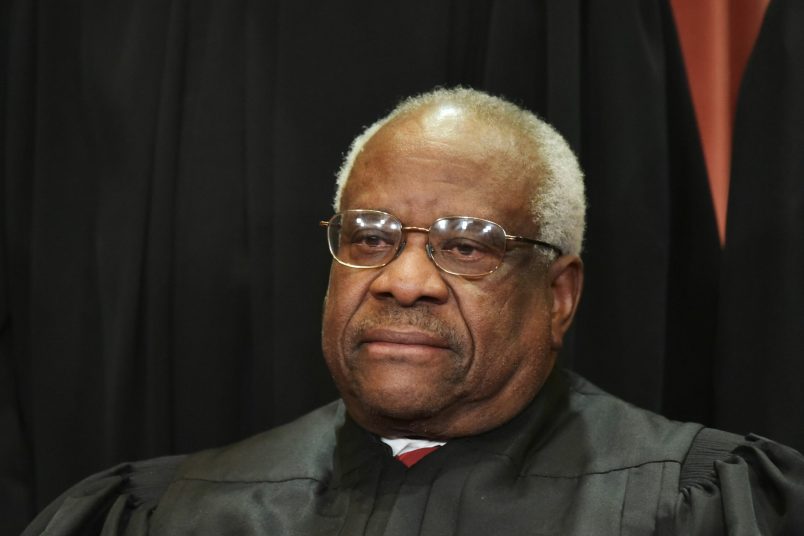

In a sneaky Monday concurrence, Justice Clarence Thomas laid the groundwork for the Supreme Court to overturn its own longstanding precedents in what may mark the beginning of efforts to destroy numerous landmark court decisions from the past decades.

The concurring opinion came in Gamble v. United States, a case regarding double jeopardy that Thomas used as a springboard to argue that the Supreme Court should review — and overturn — settled law where it is found to be “demonstrably erroneous.”

Constitutional law scholars told TPM that Thomas appeared to use the concurrence to signal to his fellow justices — and the wider public — that the new conservative majority is interested in overturning years of settled law.

“People can legitimately fear that this opinion provides a kind of intellectual cover and justification for the over-rulings that this new conservative majority may be about to engage in,” Samuel Bagenstos, a University of Michigan law professor and former Obama Administration Justice Department official, told TPM.

Melissa Murray, a professor at NYU Law, described it as an “opening salvo for those on the court…to take a more permissive view of stare decisis that is not nearly as deferential as what we’ve seen.”

Stare decisis is the principle that courts look to past precedent when deciding how to apply the law.

“He’s playing to the future,” Murray told TPM. “The only question is, is the future in a few weeks, or a few years.”

The Gamble case saw an Alabama man argue that the longstanding judicial precedent of dual-sovereignty — which holds that a crime can be prosecuted at both the federal and state levels without violating the right against double jeopardy — should be thrown out. Thomas had previously suggested that he would be open to overturning the precedent, but shot that down in the first lines of his concurrence.

“I agree that the historical record does not bear out my initial skepticism of the dual-sovereignty doctrine,” he wrote.

The justice went on to blame Congress for “duplicative prosecutions” because “by legislating beyond its limited powers, Congress has taken from the People authority that they never gave.”

He then launched into the meat of his attack on stare decisis. Thomas argued that the court “should restore” its view of the legal concept “through adherence to the correct, original meaning of the laws we are charged with applying.”

“Because the Constitution is supreme over other sources of law, it requires us to privilege its text over our own precedents when the two are in conflict,” Thomas wrote. “I am aware of no legitimate reason why a court may privilege a demonstrably erroneous interpretation of the Constitution over the Constitution itself.”

He added that “considerations beyond the correct legal meaning, including reliance, workability, and whether a precedent ‘has become well embedded in national culture’…are inapposite.”

“In our constitutional structure, our role of upholding the law’s original meaning is reason enough to correct course,” Thomas concluded.

The opinion is the third in a series of concurrences that Thomas has written this year in which he has appeared to provide a schematic for how the court could alter fundamental areas of American law. It also comes from a justice who is perceived to have influence in the Trump administration. Thomas’ wife, Ginni, hosted a White House summit with other right-wing activists that the President himself attended, and dozens of Thomas’ former clerks have received political appointments in the Trump administration or been nominated for judgeships.

It’s also the first session that the court conducted since the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy and his replacement with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, widely seen as a once-in-a generation opening for the court to strike down longstanding precedent like Roe v. Wade.

Fordham law professor Jed Shugerman told TPM that Thomas “is not really hiding the ball at all” in part because he cited and criticized Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a 1992 decision that dealt with both abortion and issues surrounding precedent.

Thomas described the decision as the type of ruling that is “not [grappling with] legal questions with right and wrong answers; they are policy choices.”

“He has been the most critical of stare decisis of any justice on the court,” Shugerman added. “That may be one signature perspective of his jurisprudence.”

Stanford Law professor David Alan Sklansky told TPM that though Thomas had “never been somebody who places a large amount of importance on sticking with” prior decisions, he had never staked out such an explicit position on the issue.

“It’s unusual to use concurring opinions to say we should be less restrained in general, across the board,” Sklansky added.

What makes the concurrence “radical” in part is its rejection of the notion that the body of American law accumulated over the centuries can provide a guide for judges, according to Bagenstos, the University of Michigan law professor.

“It’s not just trying to engage in a linguistic exercise in interpreting words from 1787, but the court today implementing a series of decisions that were made over time as this country grew and dealt with its problems,” Bagenstos said.

But for Murray, the NYU Law Professor, it was as much a statement about Constitutional law as it was a message with a narrow audience.

“It’s kind of a nudge to someone like [Chief Justice] John Roberts, who surely is in the same place that [Thomas] is with regards to the substantive outcome that he’d like to see, but probably differs on the speed,” said Murray, the NYU Law professor.

She added: “He’s saying fish or cut bait — now is the time — we have five, let’s move.”

Tierney Sneed contributed to this report.