Internal Trump campaign polling data from the 2016 election was sent to a person close to Russia’s leader, according to recently unsealed statements by a prosecutor from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s office.

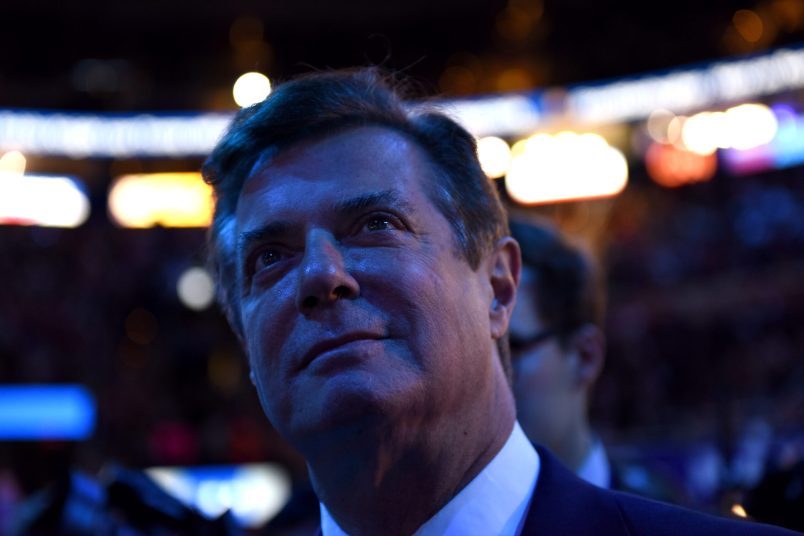

At a sealed February 2019 hearing in D.C. federal court, prosecutor Andrew Weissmann said that data shared by former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort ended up in the hands of someone close to Vladimir Putin.

“And for us, the issue of internal campaign polling data being sent to REDACTED, who the defendant conceded is extremely close to the senior leader in Russia, is in the core of what it is that the special counsel is supposed to be investigating,” Weissmann told U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson for the District of Columbia on February 4, 2019.

A transcript of the hearing was unsealed Thursday, but the identity of the person who received the data remains redacted.

The newly unsealed portions reveal for the first time the theory of the case the Special Counsel’s office was driving at in prosecuting Manafort and investigating potential collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russian government.

In the hearing, Weissmann argued that there may have been a quid pro quo arrangement, with Moscow supporting Trump’s 2016 campaign and the victorious Trump administration then supporting a potential Ukraine peace plan that would have given Russia control of Ukraine’s breakaway eastern regions.

That goes straight to how the Special Counsel’s Office appears to have viewed collusion as it applied to Manafort: in exchange for Russia helping Trump win, the theory goes, the country would “control what would be an autonomous region of the eastern Ukraine,” Judge Berman Jackson summarized at the hearing. That was, she said, “plainly something favorable to the Russians.”

Prosecutors were unable to prove the collusion case, and wrote in the Mueller Report that the probe “did not identify evidence of a connection between Manafort’s sharing polling data and Russia’s interference in the election, which had already been reported by U.S. media outlets at the time of the August 2 meeting.”

The Special Counsel’s Office suggested in the Mueller Report that Manafort’s obstruction played a role in investigators’ inability to reach a conclusion. “Several individuals affiliated with the Trump Campaign lied to the Office,” the report reads, adding that “those lies materially impaired the investigation of Russian election interference.” Manafort and his associates also had a practice of deleting messages sent via encrypted applications, meaning that investigators were unable to examine the content of their communications.

Neither Manafort nor Kevin Downing, who represented him in the Mueller investigation, returned requests for comment. Former President Trump pardoned Manafort in December 2020.

The comments were made more than two years ago during a sealed hearing to discuss whether Manafort breached a plea agreement he entered into with the Special Counsel’s Office by lying to its investigators and to a grand jury. In the transcript, scheduled to be released with fewer redactions last week but only made available on Thursday after an inquiry from TPM, some redactions remain. They appear to encompass the names of people not charged with any crimes as well as other unknown topics.

The source of Weissmann’s information is unclear; at one point, he declines to continue speaking on the court record and offers to brief the judge ex parte.

The revelation comes years after the closure of an investigation whose end — and final report — left dozens of questions unanswered.

But the newly unsealed portions of the hearing capture prosecutors’ thinking on one of the most shocking incidents uncovered both by the Special Counsel and by a bipartisan Senate investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election: that Manafort shared internal Trump campaign polling data with Konstantin Kilimnik, an alleged Russian intelligence officer. The Treasury Department said in an April 2021 statement announcing sanctions on Kilimnik that he forwarded the information on to Russian intelligence services.

The transcript also offers sharpened insight into what Weissmann appeared to see as the benefit that the Russian government stood to receive for helping elect Trump.

Weissmann described the benefit as he tried to convince Judge Berman Jackson that Manafort had lied repeatedly to the Special Counsel’s Office both about his own involvement in the peace plan and about Kilimnik’s role.

After Judge Berman Jackson asked Weissmann why Manafort appearing to lie about Kilimnik’s involvement in the plan was “important,” the prosecutor replied that the answer “goes to the heart of what the Special Counsel’s Office is investigating” and to what the “motive here is.”

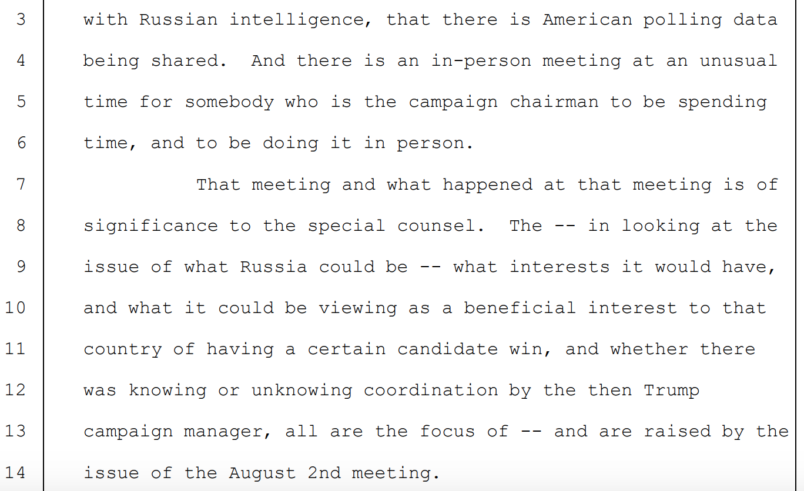

Weissmann added that the office had been scrutinizing an infamous Aug. 2, 2016 meeting between Manafort, his deputy Rick Gates, and Kilimnik at the Grand Havana Room on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Weissmann noted that the Havana Room meeting involved someone with “a relationship with Russian intelligence,” where “there is American polling data being shared.”

He went on to frame the exchange of polling information at the meeting in terms of what potential benefit Russia might receive.

“In looking at the issue of what Russia could be — what interests it would have, and what it could be viewing as a beneficial interest to that country of having a certain candidate win, and whether there was knowing or unknowing coordination by the then Trump campaign manager, all are the focus of — and are raised by the issue of the August 2nd meeting,” he added.

Judge Berman Jackson then interrupted, pressing Weissmann to describe why he thought Manafort’s work in Ukraine post-2016 was important, and why his subsequent lies to the Special Counsel’s office were as well.

Weissmann’s reply, which remains partially redacted, explained that Kilimnik had a “continuity” of interest in promoting the plan. The Mueller Report says that the alleged intelligence officer undertook “efforts to promote the peace plan to the Executive Branch (e.g., U.S. Department of State) into the summer of 2018.”

The prosecutor added that there is a document which purportedly said that Manafort would be given “access to senior people in Russia to help promote this.”

Polling data

Manafort’s attorneys sought at the hearing to argue that the polling data shared during the 2016 campaign was so granular as to be incomprehensible to anyone apart from seasoned American political operatives.

Both Mueller and Senate investigators found that Manafort briefed Kilimnik at the meeting about battleground states, and directed Gates to print out a copy of internal campaign polling data to bring to the session. Manafort had also purportedly directed Gates to periodically send campaign information to Kilimnik.

Weissmann said at the hearing that Manafort had denied directing Gates “to share the internal Trump campaign polling data.”

“That he would not, in fact, have shared anything that was so internal,” Weissmann added, describing his view of Manafort’s thinking. “That this was all about giving sort of external briefings that he would give on television shows and that he left it to Mr. Gates to just update Mr. Kilimnik.”

Gates, according to FBI notes from his interview, recalled watching Manafort discuss how the data related to “blue-collar workers” and which swing states would be in play.

Manafort and Trump’s defenders have sought to downplay the polling that was shared, arguing that it was publicly available and would likely have been useless. The newly unsealed portions of the hearing transcript show Judge Jackson asking Manafort’s attorneys why the unnamed pollster was “being paid so much to produce it and why is it covered by a NDA?”

Richard Westling, an attorney for Manafort, replied that the data was “only really significant if you do what it is that people like Mr. Manafort and others who run political campaigns do.”

“You have to have the baseline knowledge. Knowing when a certain county is thinking about a certain thing in a certain way, this is how you use it to further the campaign,” he added.

Jackson replied that Westling’s response seemed to describe why sharing the polling was “significant and unusual.”

“It’s not the sort of thing you would give to someone outside the campaign, much less outside the country,” she remarked.

Westling replied that he doubted the Russians would be able to “interpret” the information.

“So I don’t know how — the story that [it]’s being passed on to people who have no ability to speak English to begin with, beyond Mr. Kilimnik, how it’s going to be any use to anyone,” Westling added. “It would seem to me if the goal were to help Mr. Manafort’s fortunes, that some other kind of summary, something more public, more digestible might help.”