All that’s left is to dot the i’s and cross the t’s, and Michigan, powered by its shiny new Democratic trifecta, will repeal its right-to-work law.

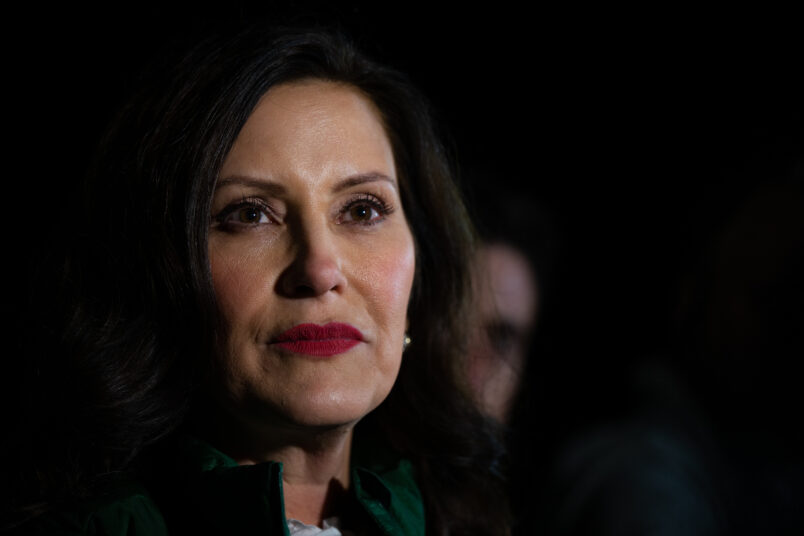

Union members cheered and clapped from the galleries as Democrats in both chambers passed the bills this month. Union leaders blasted out triumphant press releases, and Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D) made clear her intent to sign the bill.

It’s a far cry from 2012, when the right-to-work law was wending its way through the statehouse. Republicans controlled both chambers and the governor’s mansion. Pro-union protesters were arrested in the state capitol in December of that year, and then-Senate Minority Leader Whitmer was forced to call for recess, pending a lawsuit from the Michigan Democratic Party trying to push police to reopen the building.

“When it passed, if you’d asked me then whether there’s a pathway to repealing it, I’d have said no way,” Shaun Richman, who teaches labor history at Empire State University, told TPM, laughing. “It’s gone forever, man.”

Michigan’s right-to-work law hit particularly hard, given the state’s status as one of the iconic, storied union strongholds. But it wasn’t particularly unique. Around that time, in 2010 and 2011, a flurry of these laws passed across the country, propelled by a right-wing resurgence amid the rise of the Tea Party that fueled a brutal midterm “shellacking” two years after Barack Obama’s historic election.

Despite the name, these laws have nothing to do with a guarantee of employment. They allow those in unionized jobs to opt out of paying union dues — while the unions are still required to provide services, like representation in disputes with management, even to those non-paying workers. In some states they proved a fatal blow to unions, creating a “free rider” problem that undermined unions’ ability to finance their operations and organize.

“There are very, very few areas of law that require private entities to provide a service — and a union is a private entity — then bar that entity from charging a fee,” said Michael Oswalt, who teaches labor law at Wayne State University.

How We Got Here

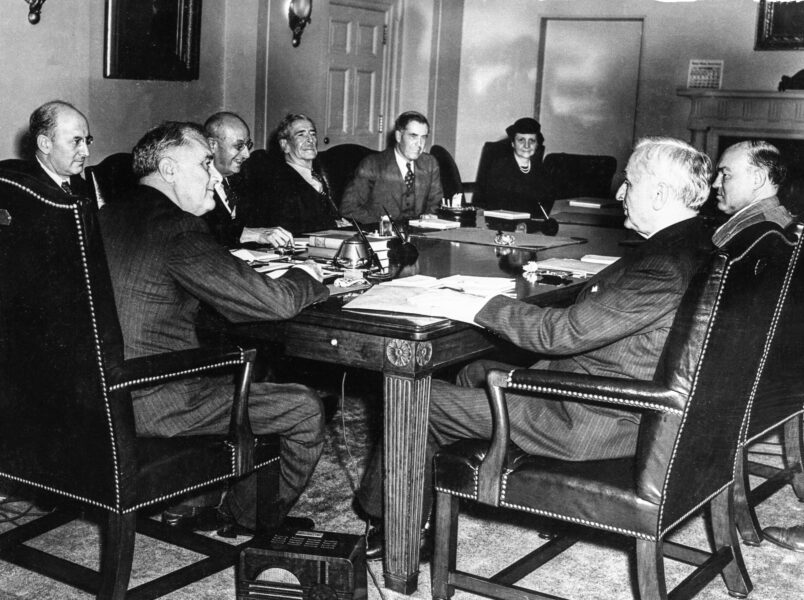

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, is a foundational law that guarantees the right of private sector employees to organize and collectively bargain. It also includes the duty of fair representation — that unions have to represent and advocate for all employees, whether they’re members of the union or not.

In 1946, Republicans won majorities in Congress for the first time in 15 years, signaling an end to the era of New Deal liberalism. They passed the Taft-Hartley Act over President Harry Truman’s veto — it was an “explicit reaction to union success,” said Erik Loomis, a professor who specializes in U.S. labor history at the University of Rhode Island — which made it illegal for unions to negotiate contracts that included joining the union as a condition of employment. That threw open the doors for states to pass right-to-work laws.

And pass them they did. These laws ripped through the South, where unions were already relatively weak.

Racial animus shot through these efforts to cripple unions, and some southern Democrats in Congress had helped Republicans beat Truman’s veto.

Openly white-supremacist lobbyist Vance Muse, during a right-to-work campaign in Arkansas just before Taft-Hartley gave these state laws life, handed out literature warning that without the law “white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black African apes whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.”

“This initial rush of right-to-work laws from around 1947 into the 1950s was primarily restricted to the former Confederacy — it didn’t really reach union strongholds,” Richman said. “It eventually extended to the Sun Belt, with a real swelling point in Arizona and Nevada.”

In 1957, a right-to-work law finally took down a real union Goliath: Indiana.

This encroachment into true union territory was significant, but relatively short-lived; the state repealed the law in 1965. It would be the last time a state repealed its right-to-work law — a chapter that will conclude this year when Michigan repeals its law, over 50 years later.

After Indiana’s repeal, the right-to-work push settled into decades of relative “stasis,” Richman said. “These are union states and those are confederacy states, as it ever was,” he said.

Hope, No Change and the Filibuster

From President Lyndon B. Johnson on, Democrats made a run at labor reform whenever they won complete control of Congress. And each time, they failed.

In 1966, when Johnson enjoyed the massive congressional majorities that helped him pass his Great Society agenda, a law that would repeal the section of Taft-Hartley that greenlights right-to-work laws passed through the House. But it was stymied in the Senate, thanks to a filibuster by both Republicans and southern Democrats.

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter oversaw an attempt to reform the National Labor Relations Act in response to some employers finding it cheaper to just flout the law and prevent workers from organizing. The bill passed through the House before crashing up against a five-week conservative filibuster in the Senate.

In 1994, a Republican Senate filibuster again thwarted a Democratic president’s attempts at reform, this time killing President Bill Clinton’s push to block companies from hiring permanent replacements for striking workers. An attempt to make it easier to form a union fizzled under Obama in 2009, and Democrats were unable to pass the PRO Act — which would, among other things, let unions override right-to-work laws — through the Senate during the first two years of unified control under President Joe Biden.

“Usually, it’s not just the filibuster, though that’s important,” Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor who directs the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told TPM of the years of failed attempts. “It’s also because a slice of the Democratic Party is against labor law reform.”

Democratic Roadblocks, Republican Action

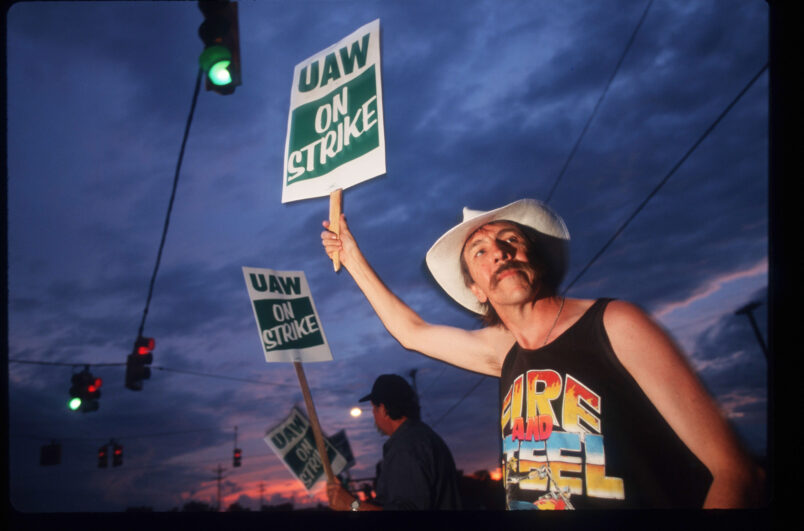

In the background of these stymied opportunities at the federal level, right-wing forces focused on propagating right-to-work laws throughout the states with pinpoint precision. Following Obama’s triumph in 2008, the irate right wing of the Republican Party — funded by titans of capital like the Koch brothers and guided by players including the American Legislative Exchange Council, which pushes and distributes model legislation to Republican state legislators — homed in on legislatures in states that were once union strongholds.

“These right-to-work laws moved with blinding speed, in Wisconsin, in Michigan, in all of these places,” Richman said.

Indiana, which had fought off its right-to-work law in the mid-’60s, adopted a new one in 2012.

Studies show that workers suffer economically in states ruled by right-to-work laws. They lead to greater economic inequality in highly unionized areas by blunting the power of labor unions, per a 2020 study. An Economic Policy Institute study from 2015 found that wages in right-to-work states were 3.1 percent lower than in non-right-to-work states.

And perhaps even more surprisingly, it seems that right-to-work laws directly hurt the Democratic Party. A 2018 study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that right-to-work laws reduce Democratic presidential vote shares by 3.5 percentage points, with similar effects on Senate, House, gubernatorial and state legislative races. The study also found that turnout drops by 2 percentage points in right-to-work counties after passage, and that it dampens labor contributions to Democratic candidates and makes it less likely that potential Democratic voters are contacted to vote. It also reduces the number of working class candidates elected, while state policy marches towards the right.

“Labor unions are also important forces in protecting and expanding democratic institutions,” Jake Grumbach, an associate professor of political science at the University of Washington, told TPM. “My research with Paul Frymer shows that labor union membership makes white workers more racially solidaristic and less susceptible to the culture war politics that threatens democratic stability.”

Michigan and Beyond

While repealing its right-to-work law will only directly apply to a limited universe of workers — union members represent about 14 percent of wage and salary earners in Michigan — it marks a distinct shift in how unions are being perceived and how the Democratic Party is embracing them.

“Michigan is the birthplace of modern industrial unionism,” Lichtenstein said. “Democrats are finally being bold in a way that Republicans have always been bold.”

Many experts juxtaposed Michigan with Virginia, which didn’t even try to repeal its right-to-work law when it had Democratic trifectas in 2020 and 2021.

“Michigan doing so not only reclaims their traditional role at the front line of the labor movement, but it suggests that to be a Democrat in the 2020s means you have to be pro-union,” Loomis said.

Biden has centered unions in his speeches and trips much more than Democratic presidents in recent history, and the pre-2020 campaigns of Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) centered both workers’ rights and labor reforms. Some point to President Donald Trump’s 2016 victory as helping plant these seeds, as Democrats became acutely aware of increasing erosion in support from white, blue-collar workers, and to a lesser degree from working-class Latinos and African American men, that could doom them to prolonged electoral peril.

Public approval of unions, meanwhile, is at the highest it’s been since the mid-’60s.

There are still significant obstacles to a tidal wave of union strength upending economic inequality and shifting power back to workers.

“Until labor law changes, unions are unlikely to have a significant turnaround because it’s simply too hard to actually form a union,” Oswalt said.

“The process of forming a union is still rigged against workers and against unions,” Richman added.

But the sparks are undeniable. Movements have grabbed headlines from Starbucks coffee shops and Amazon warehouses, where baristas and workers are fighting back against immense corporate power. Unionism has swept through media outlets and college faculties, transforming those professions.

Strengthening union power — which will only realistically happen when Democrats pivot from their decades of complacency and start going to the mat for labor, out of conviction or self-interest or both — will help these movements win what is currently a lopsided battle.

“The working class always advances in a layered fashion,” Lichtenstein said. “In the 19th century, it was German and Irish immigrants. In the ‘30s, it was eastern European second generation immigrants and Jews. In the ‘50s, it was African Americans. Today it’s mostly college educated workers.”

“A union is not just the people who are in it at this moment,” he added. “It’s immortal.”