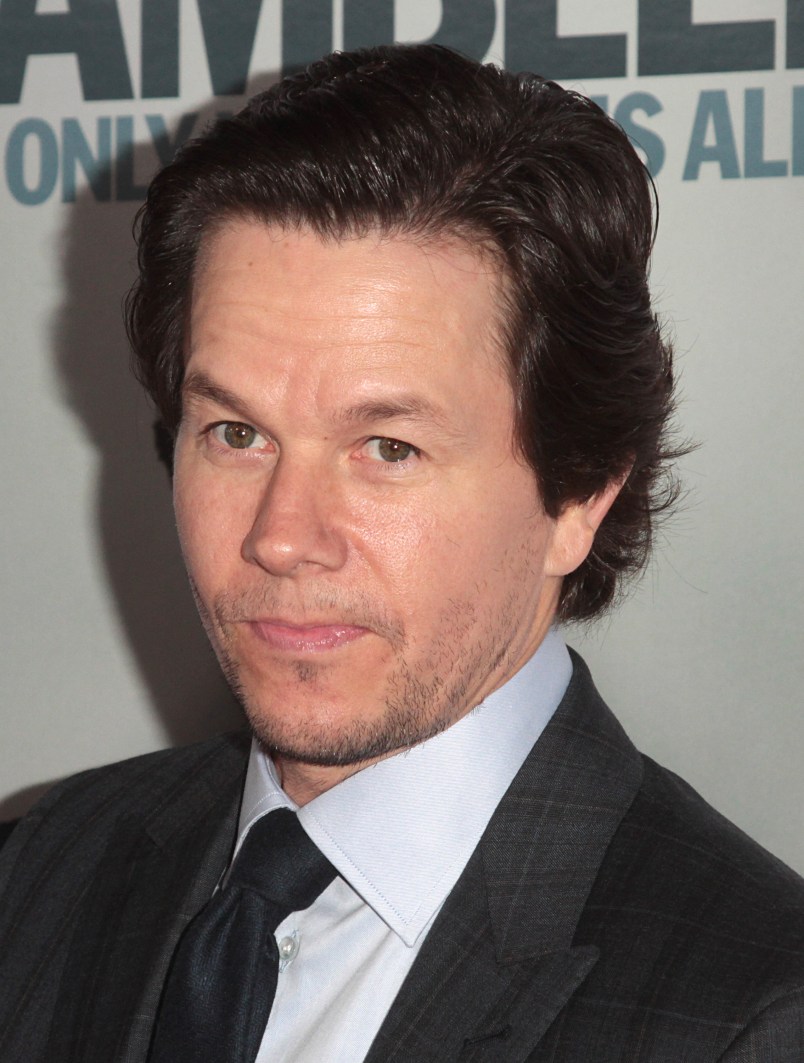

BOSTON (AP) — Victims of one of Mark Wahlberg’s racially motivated attacks as a teenage delinquent in segregated Boston in the 1980s are divided over whether he should be granted a pardon for his crimes.

Kristyn Atwood was among a group of mostly black fourth-grade students on a field trip to the beach in 1986 when Wahlberg and his white friends began hurling rocks and shouting racial epithets as they chased them down the street.

“I don’t think he should get a pardon,” Atwood, now 38 and living in Decatur, Georgia, said in an interview with The Associated Press.

“I don’t really care who he is. It doesn’t make him any exception. If you’re a racist, you’re always going to be a racist. And for him to want to erase it I just think it’s wrong,” she said.

Mary Belmonte, the white teacher who brought the students to the neighborhood beach that day, sees things differently. “I believe in forgiveness,” she said. “He was just a young kid — a punk — in the mean streets of Boston. He didn’t do it specifically because he was a bad kid. He was just a follower doing what the other kids were doing.”

The 43-year-old former rapper, Calvin Klein model and “Boogie Nights” actor wants official forgiveness for a separate, more severe attack in 1988, in which he assaulted two Vietnamese men while trying to steal beer. That attack sent one of the men to the hospital and landed Wahlberg in prison.

Wahlberg, in a pardon application filed in November and pending before the state parole board, acknowledges he was a teenage delinquent mixed up in drugs, alcohol and the wrong crowd. He points to his ensuing successful acting career, restaurant ventures and philanthropic work with troubled youths as evidence he’s turned his life around.

“I have apologized, many times,” he told the AP in December. “The first opportunity I had to apologize was right there in court when all the dust had settled and I was getting shackled and taken away, and making sure I paid my debt to society and continue to try and do things that make up for the mistakes that I’ve made.”

Court documents in the 1986 attack identify Wahlberg among a group of white boys who harassed a school group as they were leaving Savin Hill Beach in Dorchester, a mixed but segregated Boston neighborhood that had seen racial tensions during the years the city was under court-ordered school integration.

The boys chased the black children down the street, hurling rocks and racial epithets including “Kill the n—–s!” until an ambulance driver intervened. Wahlberg was 15 at the time.

Atwood still bears a scar from getting hit by a rock. No one was seriously injured, but the attack left other invisible — and indelible — scars.

“I was really scared. My heart was beating fast. I couldn’t believe it was happening. The names. The rocks. The kids chasing,” Belmonte told the AP.

Wahlberg and two other white youths were issued a civil rights injunction: essentially a stern warning that if they committed another hate crime, they would be sent to jail.

In 1988, Wahlberg, then 16, attacked two Vietnamese men while trying to steal beer near his Dorchester home.

According to the sentencing memorandum, he confronted Thanh Lam, a Vietnamese immigrant, as he was getting out of his car with two cases of beer. Wahlberg called Lam a “Vietnamese f—— s—” and beat him over the head with a 5-foot wooden stick until Lam lost consciousness and the rod broke in two.

Documents say Wahlberg ran up to another Vietnamese man, Hoa Trinh, and asked for help hiding. After a police cruiser drove past, he punched Trinh in the eye. Later, he made crude remarks about “slant-eyed gooks.”

Wahlberg ultimately was convicted of assault and battery, marijuana possession and criminal contempt for violating the prior civil rights injunction. Trinh declined to be interviewed by AP, and efforts to locate Lam were unsuccessful.

Judith Beals, a former state prosecutor involved in the cases, said Wahlberg’s crimes stand out because he violated the injunction with an even more violent attack on people of yet another race.

“It was a hate crime and that’s exactly what should be on his record forever,” Atwood said.

___

AP reporters Johnny Clark in Atlanta, Steve LeBlanc in Boston and John Carucci in New York contributed to this report.

Copyright 2015 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.