As the Supreme Court weighed the future of President Joe Biden’s student debt relief program, the right-wing justices brought up the same “doctrine” they nearly always do during questions of agency power: the major questions doctrine.

It’s an idea — increasingly embraced and pushed in right-wing legal circles — that courts should require explicit writs of authority delegated by Congress, and not defer to agency interpretation of the laws, when the action the agency wants to take is of “vast economic or political significance.”

If the definition seems squishy, it’s because it is — all the better for a Supreme Court that has handed down decision after decision limiting agency power.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar (and the liberal justices) argued Tuesday that the 2003 statute giving the Secretary of Education his power in this case could hardly be more explicit: It says that the Secretary “may waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs” as the Secretary “deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency.”

The Biden administration is tying the relief to economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

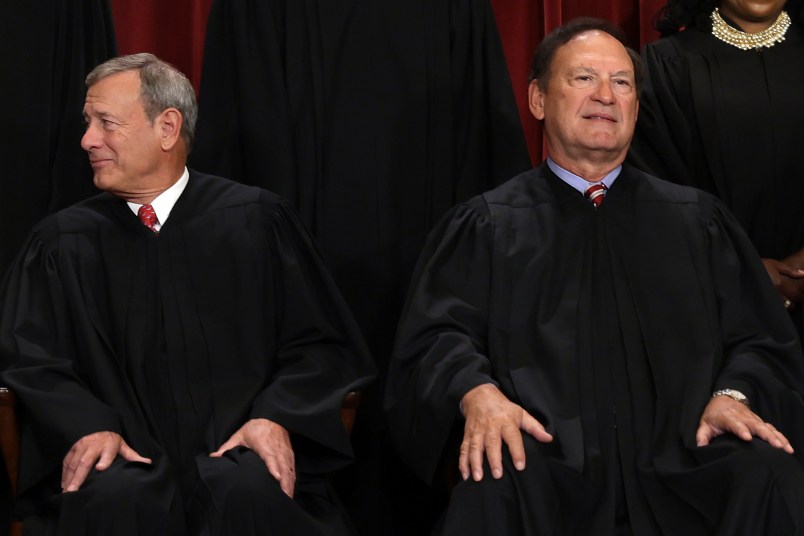

Chief Justice John Roberts, leaving little mystery as to where he stands, hammered major questions throughout, seemingly most troubled by the sum of the loans the program would forgive.

“Your argument here is that no notice and comment proceeding was required before the action taken on a half trillion dollars of loans and because the President can act unilaterally, that there is no role for Congress to play in this either,” he said to Prelogar, emphasizing the sum.

“And at least in this case, given your view of standing, there’s no role for us to play in this either,” he continued. “We take very seriously the idea of separation of powers and that powers should be divided to prevent its abuse.”

Prelogar responded that there is a role for the judiciary with proper plaintiffs — the government is arguing that the states suing don’t have standing — and that Congress has already played its most central role by writing and passing the statute that empowered the secretary.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh too waxed philosophical on the nobility of hemming in executive power.

“Some of the biggest mistakes in the Court’s history were deferring to assertions of executive emergency power; some of the finest moments in the Court’s history were pushing back against presidential assertions of emergency power,” he said, citing the Korean War and the post-Sept. 11 period. “Given that history, there’s a concern I suppose that I feel at least about how to handle an emergency assertion.”

He quoted an amicus brief calling the debt relief program a “case study in abuse of executive emergency power.”

Prelogar underscored the distinction between regulatory schemes and programs like the student debt one, saying that the Court can put aside intensive major questions scrutiny when the agency is trying to provide a benefit versus sublimating individual rights to regulations.

The liberal justices jumped in at points to swat down their conservative peers’ argument.

“Congress used its voice in enacting this piece of legislation,” Justice Elena Kagan said of this 2003 law. “All this business about executive power — we worry about executive power when Congress hasn’t authorized the use of executive power. Here, Congress has authorized the use of executive power in an emergency situation.”

“We deal with congressional statutes every day that are really confusing — this one is not,” she added.

This case highlights the usefulness of the major questions doctrine for the right-wing majority when it wants to stymy the administration. A congressional statute can never be explicit enough, and any policy could be inflated to have “vast economic or political significance” when those judgements are completely subjective.

This statute allows the Secretary of Education to waive or modify any part of student debt programs during times of national emergency. And still, multiple justices invoked the term “abuse” in characterizing it.

They tend to paint these executive branch actions as tyrannical power grabs, twisting congressional intent and wresting authority away from the legislature, the people’s branch. They tend not to mention that, in the process of shackling the rampaging executive branch, they’re appropriating an awful lot of power to themselves.