WASHINGTON (AP) — During the special counsel’s Russia investigation, Konstantin Kilimnik has been described as a fixer, translator or office manager to President Donald Trump’s ex-campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

But Kilimnik, an elusive figure now indicted alongside Manafort on witness tampering charges, was far more involved in formulating pro-Russia political strategy with Manafort than previously known, according to internal memos and other business records obtained by the AP.

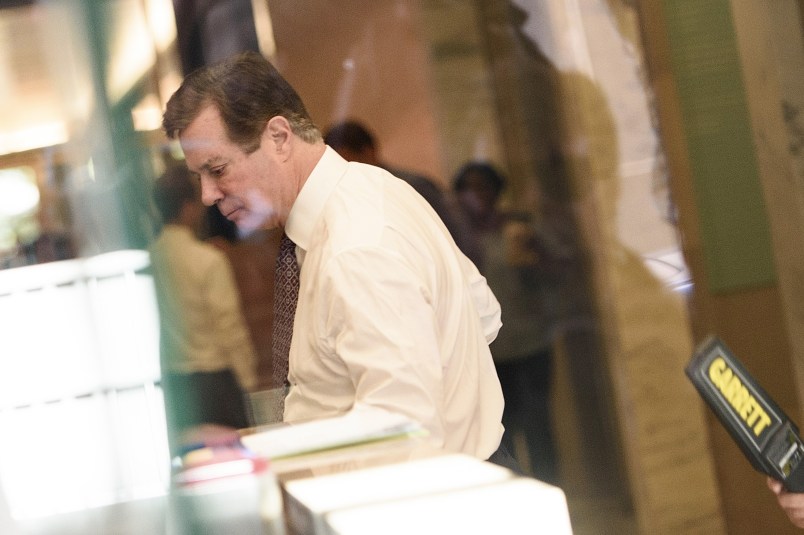

The records include a rare 2006 photograph of Kilimnik, a Ukrainian native, in an office setting with Manafort and other key players in Manafort’s consulting firm at the time. Some of the documents were later independently obtained by U.S. government investigators.

More than a decade before Russia was accused of surreptitiously trying to tilt the presidential election toward Trump, Manafort and Kilimnik pondered the risks to Russia if the country did not hone its efforts to influence global politics, the records show.

“The West is just a little more skillful at playing the modern game, where perception by the world public opinion and the spin is more important than what is actually going on,” Kilimnik wrote to Manafort in a December 2004 memo analyzing Russia’s bungled efforts to manipulate political events in former Soviet states. “Russia is ultimately going to lose if they do not learn how to play this game.”

Kilimnik — who special counsel Robert Mueller believes is currently in Russia and has ties to Russian intelligence — helped formulate Manafort’s pitches to clients in Russia and Ukraine, according to the records. Among Manafort’s clients were Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska and other mega-wealthy Russians with close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Kilimnik began that work in secret, the records show, even while working for the International Republican Institute — a U.S. government-funded nonprofit supporting the Western-friendly democratic movements that Manafort and his patrons sought to counter.

The records do not reveal what motivated Kilimnik’s work for Manafort, though Mueller’s team has alleged in U.S. court filings that Kilimnik’s ties to Russian intelligence remained active through the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. Kilimnik has denied that.

The records show Kilimnik helped conceive strategies that Manafort sold to clients, and that he served as a key liaison between Manafort and principal financial backers, including Deripaska.

Deripaska has denied hiring Manafort for any pro-Russian political work, and unsuccessfully sued the AP last year over reporting that he had paid Manafort more than $10 million to influence political decisions and news coverage in Eastern Europe and Western capitals. Manafort also denied to the AP last year that he had performed political work for Deripaska.

A new filing by the U.S. government in Manafort’s court cases showed that Manafort acknowledged that work in a 2014 FBI interview, and files seized by the FBI showed that Deripaska was the source of a $10 million loan to a Manafort-controlled company in 2010.

At least some of Kilimnik’s channels to Deripaska remained open through the 2016 presidential campaign, when Kilimnik and Manafort sought to return to the oligarch’s good graces after a falling out. Deripaska has said he never received or discussed any proposal for new Manafort business during the campaign.

Born in what was then Soviet Ukraine, Kilimnik was studying as a linguist at a state-run military university when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. After a stint in the military, he joined the International Republican Institute as a translator in 1995 and rose to become the acting head of its Moscow office.

The post-Soviet period was a heady time for the IRI, a nonprofit long headed by Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. Among its greatest causes was Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, when street protests thwarted a clumsy attempt by a Russian-backed government to steal the country’s 2004 presidential election.

Even before the Orange Revolution had run its course, Kilimnik had begun secretly working with Manafort to undermine it, the records obtained by the AP show. By December 2004, he was already working for Manafort — not as a translator, as he told the New York Times earlier this year in a rare interview, but as a strategist.

In one memo, Kilimnik noted the failings of Soviet-style heavy-handed tactics, including Russia’s lack of experience with competitive elections after decades of one-party rule.

“Russian political consultants, skilled at manipulating virtual public opinion and achieving virtual results in virtual elections, were useless,” he wrote.

Other documents from the period identified Manafort’s client as Deripaska, a Russian billionaire with business ties to the Kremlin.

When the IRI learned in March 2005 that Kilimnik was working for Manafort, Kilimnik was abruptly fired. From then on, he worked full time for Manafort, earning a base monthly salary of $10,000, according to the records.

Manafort proposed Kilimnik as the firm’s direct liaison with Deripaska’s main business, known as Basel, short for Basic Element.

Whether that occurred is not clear. But Deripaska hired Manafort’s firm — and Kilimnik became a key player in the work.

U.S. officials regarded Kilimnik as Manafort’s key aide during their work on behalf of pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych, who became the president of Ukraine in 2010. A representative from the U.S. Embassy in Kiev would occasionally meet with Kilimnik to discuss current political affairs, according to a former senior U.S. official who was not authorized to discuss the issue publicly and thus spoke on condition of anonymity.

The records show that Kilimnik participated in an early Manafort plan to influence Western politicians and media outlets. Officially, the project — known as Eurasia21 — would offer news and expertise on former Soviet states. Unofficially, it would be a propaganda operation intended to target Washington and European capitals and “train a cadre of leaders who can be relied upon in future governments,” according to one memo.

A website was launched with some initial funding from the investment bank Rothschild, a Deripaska ally, but the project fizzled and folded. The plan was a model for covert lobbying work later by Manafort, however. Those efforts included using the European Centre for a Modern Ukraine — an alleged front group used by Manafort to route millions of dollars for covert lobbying work in Washington — and the so-called Hapsburg Group, a stable of former European politicians secretly paid to espouse positions in keeping with Yanukovych’s government.

Even after Manafort lost his campaign job and was indicted by Mueller on charges related to his foreign lobbying work, U.S. prosecutors alleged, Kilimnik helped ghost-write an op-ed defending Manafort under the name of Oleg Voloshyn, a former Ukrainian government official. Manafort also faces bank fraud and tax evasion charges in Virginia.

Other Manafort associates — including his deputy Rick Gates — have not shown the same steadfastness toward Manafort as Kilimnik. Gates has pleaded guilty to helping Manafort launder millions of dollars through bank accounts in Cyprus.

Days after Gates’ guilty plea, prosecutors said Kilimnik attempted to tamper with a witness by reaching out to a person connected with Manafort’s lobbying work.

And as recently as April, Kilimnik contacted two witnesses in the Mueller investigation on behalf of Manafort, according to court filings.

“Hey. This is Konstantin,” Kilimnik wrote via the WhatsApp messenger, according to the filings. “My friend is looking for ways to connect to you to pass you several messages. Can we arrange that?”