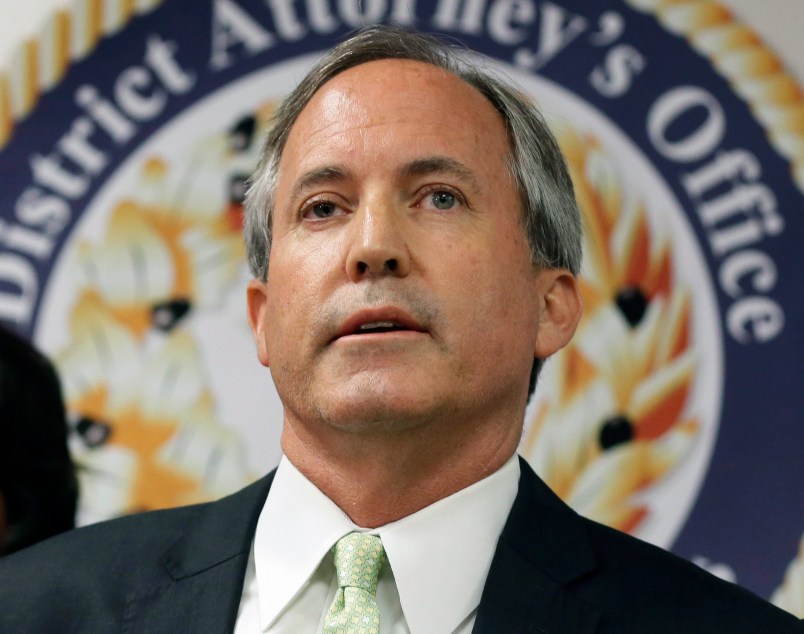

AUSTIN, Texas (AP) — When a small county in the Colorado mountains banished everyone but locals to blunt the spread of the coronavirus, an unlikely outsider raised a fuss: Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who called it an affront to Texans who own property there and pressed health officials to soften the rules.

“The banishment of nonresident Texas homeowners is entirely unconstitutional and unacceptable,” Paxton said in a news release April 9, when his office sent a letter asking authorities in Gunnison County to reverse course.

An Associated Press review of county and campaign finance records shows Paxton’s actions stood to benefit an exclusive group of Texans, including a Dallas donor and college classmate who helped Paxton launch his run for attorney general and had spent five days trying to get a waiver to remain in his $4 million lakeside home. Robert McCarter’s neighbors in the wealthy Colorado enclave of Crested Butte are also Paxton campaign contributors, including a Texas oilman who has given Paxton and his wife, state Sen. Angela Paxton, more than $252,000.

Less than three hours after Paxton announced the letter, Gunnison County granted McCarter an exemption to stay, according to documents obtained by AP. The county says the timing was coincidental.

The depth of Paxton’s connections in the heart of the Rocky Mountains, which were not previously known publicly, raise questions about Texas’ top law enforcement officer using his office to lean on a secluded Colorado county as it scrambled to keep COVID-19 at bay. Paxton has at least nine donors in Texas who own property in Gunnison County, and who collectively have given him and his wife nearly $2 million in political contributions. He sent the letter even as his own state was requiring people arriving from New Orleans and New York to self-quarantine for 14 days.

Paxton spokesman Marc Rylander said in an email that “it is a normal practice for the attorney general to speak with multiple constituents from around Texas about issues pertinent to Texas residents.” Asked whether Paxton had spoken to McCarter or other donors before getting involved in Gunnison County, another spokeswoman, Kayleigh Date, said they could not reveal specific homeowners.

McCarter did not respond to multiple calls and emails seeking comment.

Paxton, a Republican who is in his second term, has raised his national profile as a conservative crusader under President Donald Trump, including leading a lawsuit against the Affordable Care Act that goes before the Supreme Court this fall. He also has spent nearly his entire five years in office under felony indictment for securities fraud. Paxton has pleaded not guilty, and the case has stalled for two years over legal challenges.

Legal experts and watchdogs say Paxton getting involved in Gunnison County could deserve attention from Texas ethics regulators.

“If Attorney General Paxton used his position to deliberately intervene with Colorado officials to benefit a major campaign donor, the Texas Ethics Commission should immediately investigate whether he violated state laws,” said Daniel Stevens, executive director of the left-leaning Campaign for Accountability in Washington.

Gunnison County, some 200 miles (320 kilometers) southwest of Denver, has reported more than 100 cases of the virus and at least four deaths. The remote community of 17,000 people has only one hospital with 24 beds and no intensive care unit, and health officials cited the scarcity of resources in ordering nonresidents to leave.

Fewer than 2,000 property owners are from Texas, according to the Gunnison County Assessor’s Office. The county says the average home value in 2019 was more than $578,000, and Mountain Living magazine in 2017 described McCarter’s neighborhood as a place “where the rustic homes resemble national park lodges.”

Prior to Paxton’s letter, McCarter asked the county twice about getting a waiver, writing that his family was healthy and had a “freezer full of elk” from a hunting trip that would last for months, according to documents obtained under Colorado open records laws.

Gunnison County Manager Matthew Birnie said Paxton’s letter did not influence McCarter getting a waiver, or later changes to the public health order.

“Our public health officials had no knowledge of the connection between the McCarters and AG Paxton and even if they had it would have had no effect on decision-making,” Birnie said.

Paxton and McCarter attended Baylor University in the 1980s, and a yearbook shows them together in group photos. McCarter’s only political contribution in Texas campaign finance records is a $5,000 donation to Paxton in 2013, on the day Paxton filed his candidacy for attorney general.

McCarter’s neighbors include Texans who made far bigger contributions, though records show none of them asked for waivers during the lockout. They include Midland oilman Kyle Stallings, who has given Paxton and his wife more than $252,000 in individual donations. He declined comment.

Houston homebuilder Richard Weekley also has property in Gunnison County and has helped steer $1.6 million in political contributions to the Paxtons. A spokeswoman says he has been staying in Houston and had not discussed the Colorado restrictions with Paxton.

___

Bleiberg reported from Dallas. Associated Press researchers Randy Herschaft, Rhonda Shafner and Jennifer Farrar in New York contributed to this report.

___

Follow Jake Bleiberg at www.twitter.com/jzbleiberg and Paul J. Weber at www.twitter.com/pauljweber.

___

Follow AP news coverage of the coronavirus pandemic at http://apnews.com/VirusOutbreak and https://apnews.com/UnderstandingtheOutbreak.