As midnight approached on November 3, 2020, Ken Matta was sitting in a Phoenix conference room with Arizona’s secretary of state. And he was feeling pretty good.

Sure, COVID-19 had disrupted his office’s typical election plans, but the secretary’s team had pulled off one of the smoothest elections in years.

It took a lot of work to make it happen. They had received unprecedented help from the federal government. County election offices had become a buzzing hive of activity, cooperating with each other and sharing best practices. The counterterrorism “fusion center” in Arizona — which was stocked that day with intelligence and law enforcement officials from every level of government — had overseen an Election Day without a hitch.

And so Matta, the election security lead in Arizona and a nearly 20-year veteran of the secretary of state’s office, was optimistic.

“We built this great community in Arizona, like never before,” said Matta. “We felt so good. A week before the election, we’re looking at each other going like, ‘Alright, what else can we do?’ It’s not very often when we get a chance to say, ‘You know what, we’re sitting pretty.’”

Then, the President of the United States appeared on television. As he started to speak, Matta’s heart sank. The election, Donald Trump said, was a fraud on the American people.

That speech by Trump, falsely claiming victory just after 2 a.m. in Washington, marked the beginning of months of attacks on election workers, like Matta, that continue today. Matta had worked in government for two decades after being bitten by the election security bug during the 2000 Bush v. Gore recount. He had never seen anything like it.

“Instantly, our lives changed,” he recalled in an interview with TPM. “None of us in the whole industry at that moment felt safe and secure. That’s the good name of elections thrown under the bus. And we had worked harder up to that point than we ever had before to make sure the elections were secure.”

That work didn’t matter: They were standing between Trump and power. What Matta witnessed in the 18 months since Trump’s election-night proclamation has made him fear for the future of American democracy: a sustained attack on election workers, and the resulting attrition and political gamesmanship that he says will allow conspiracy theorists and political operatives into key jobs in election administration, including secretary of state positions — the officials who in many state run elections.

The arsonists, in other words, are now arriving at the firehouse.

Matta left state government this month.

“I’m worried that people that only follow a political agenda get into power and have control over our elections,” he said. “If we get to that point, the outlook is bleak.”

Assault Rifles, Threats To ‘Hunt’ Election Workers, And A Creepy Gas-X Gift Box

Nov. 3, 2020, which should have been nearly the finish line to a challenging election year, turned out to be the start of something new.

After Trump’s election-night address, “we swung into debunking mode,” Matta said. The office began strategizing how to fight back against the misinformation, working out communication strategies to address the President’s lies. But the lies were already bearing fruit.

The calls started rolling into the secretary’s office: Harassment, threats. A mob swarmed the Maricopa County voter tabulation center. Political operatives began their work to overturn Joe Biden’s victory. Alex Jones showed up in the state. Soon, Rudy Giuliani arrived too, to meet with state legislators and hold a theatrical “hearing” on supposed voter fraud.

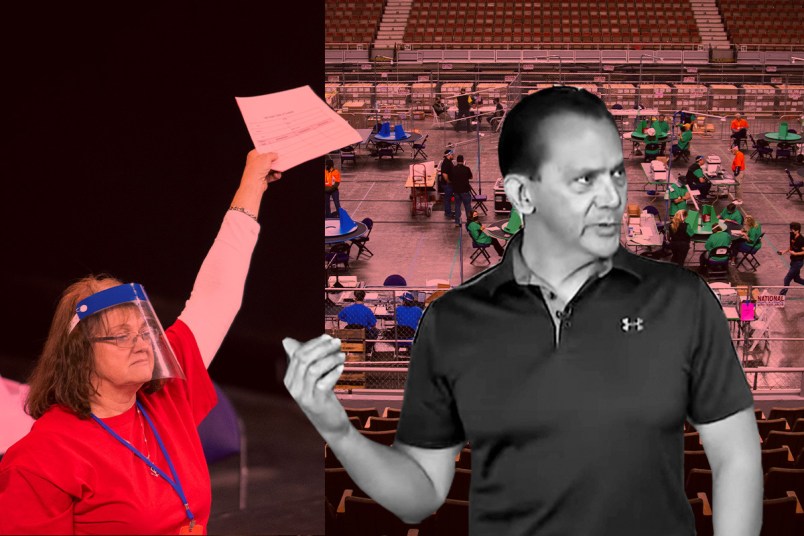

It didn’t end with Joe Biden’s inauguration, of course. A few weeks later, the Republican-controlled state Senate subpoenaed all 2.1 million ballots from Maricopa County, handing them over to a group of privately-funded conspiracy theorists led by the contractor Cyber Ninjas, which began a sham “audit” that included recounting the ballots and inspecting them for bamboo fibers — sure signs of meddling from Asia, the theory went.

Matta witnessed that whole episode first-hand, including as an observer of the “audit” for the secretary of state, where Cyber Ninjas’ audit workers often tried to convince him that he and his colleagues would end up in jail.

At one point, Matta began noticed pro-audit demonstrators with assault rifles eyeing the cars entering the state fairgrounds, where ballots were being stored and recounted at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum.

He, too, began carrying a gun.

But equally alarming for him was the treatment of millions of voters’ ballots: Matta saw audit workers mistakenly double-count 100 overseas and military ballots, but only after they’d mistakenly believed they’d uncovered evidence of fraud. Later, when the audit contractors moved into a new building, rain dripped from a leaky roof directly onto ballot boxes, and Matta saw ballots sag in the humid, un-air-conditioned room.

“They didn’t even know how many ballots they had,” he scoffed a year later, in an interview with TPM. “Their numbers didn’t jive at all.”

The audit also revealed the disdain that Trump’s true believers had for the state employees.

Audit workers were “questioning our integrity, our democratic allegiances, our sexuality,” he recalled. “It was tough to walk through that everyday.”

At the end of the ordeal, he found a “very creepy” gift box waiting on a table for him. Inside was a plastic cockroach that audit workers had repeatedly placed on his phone, a bottle of Pepto Bismol (a reference to the pink shirts that secretary of state observers were forced to wear), a seat-saver for a Trump rally with Matta’s name on it, a ticket stub for audit bankroller Patrick Byrne’s “Deep Rig” conspiracy theory movie, red and green pens, and a pack of Gas-X, which Matta said referred to the audit workers’ repeated taunts to the state observers that they should be anxious about the outcome of the audit — they would, after all, soon be behind bars.

“They were always saying, ‘Are you nervous? Because you’re going to jail.’”

‘Lying Awake At Night’

Matta spoke to TPM a few weeks after leaving his job at the secretary of state’s office. He was worried about the attrition of election workers in the face of continued attacks and threats. At the secretary of state’s office, he reviewed at times more than 30 threats a day that were sent to employees in the office, everything from menacing emails to voicemails informing staff that they would “be hunted.” The number of threats flagged to him eventually tapered, but Matta thought that may have simply been because employees grew “calloused” to their lives being threatened.

Across the country, an alarming number of election workers are leaving their jobs, as are seasonal poll workers. Conservative activists have taken note, and are working hard to replace them with true believers.

“If you’re a senior citizen — we’ve heard them say, ‘Why would I volunteer to go get shot up at the polls or something for this amount of money?’” Matta said.

He thinks election deniers are bound to fill those gaps.

Matta observed that election security officials have spent decades honing their craft, and that it still is quite difficult to affect election results through cheating. The bigger risk, he said, could be what the Maricopa County audit and others like it around the country have sought to do: Spread doubt about whether voters can ever truly trust election outcomes.

For an industry based on trust and good faith, Matta said, the last eighteen months have been torture for well-meaning election workers across the country.

“Things haven’t gone back to normal,” he said. “People that aren’t working are lying awake at night thinking about this stuff. It eats on your soul, it’s all-consuming. It hasn’t stopped.”