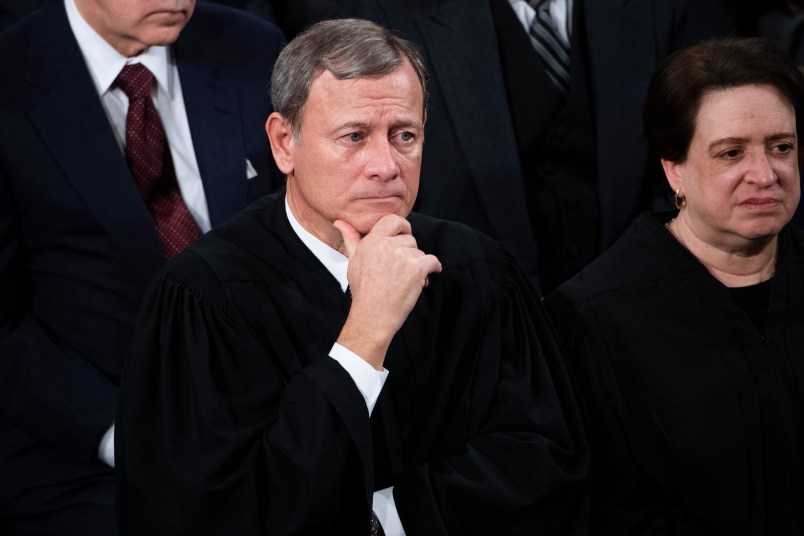

In opinions that came down this summer, Chief Justice John Roberts seemed to be settling into a new era of the Supreme Court, with him as the swing justice. But that era may already be over, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death on Friday.

In giving Republicans the opportunity to cement 6-3 conservative control of the court, Ginsburg’s death made it much harder for Roberts to steer the court in a more moderate direction in cases where the conservative position put its legitimacy at risk.

The two terms during which he served as the median justice on the court — a position he took over after Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement in 2018 — showed that Roberts was willing to play that role. Regardless of who emerges as the new median justice, there will be fewer occasions for the swing justice to exert influence in a 6-3 court than in the closely divided 5-4 court that persisted for years.

“John Roberts has tried very hard to keep the court out of extreme hot water. He has a keen sense of the institutional interest of the court and rises above his own ideological preferences at times, and that effort will largely be lost,” Barry Friedman, a professor at the New York University School of Law, told TPM.

Roberts is by no means a moderate like Kennedy, and on key issues like church v. state and voting rights, he has already pulled the court farther right than what would have been expected with Kennedy still on the bench.

But in cases like the challenge to President Trump’s census citizenship question and whether Trump could unravel deportation protections for young immigrants, Roberts has been able to find narrow reasons to vote with the liberals, and in the process, defuse major political bombs. The 7-2 decisions that Roberts secured in this year’s high stakes Trump subpoenas, meanwhile showcased the chief’s ability to use his leverage to build decisions that protect the court from accusations of pure partisanship.

Just as telling were the cases the Supreme Court didn’t take up while Roberts has been the median justice, such as several cases which would have allowed the court to significantly expand gun rights. Many believe the court passed up those cases because the conservative justices did not believe a Roberts vote in their favor was guaranteed.

In recent decades, who constitutes the court’s “swing” justice has been shifting to the right — from Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in the 1990s and early 2000s to Justice Kennedy in the decade or so after that — with every major shake up.

But as chief justice, Roberts also has an additional interest in navigating the court away from a reputation that it was only interested in ruling on the side of Republicans. Even while he still had Kennedy on the court to his left, that interest appeared to play a major role in cases like the two Obama-era Affordable Care Act challenges when he broke with conservatives to uphold the law.

“The data shows that he does moderate in cases that seem to have implications for the legitimacy of the court or keeping courts out of highly political situations,” James Weinstein, a law professor at Arizona State, told TPM.

The distrust the Republican base has for Roberts because of his ACA decision was only exacerbated in how he handled the cases involving census and the deportation protections for young immigrants. Roberts’ personal ideological preferences took a back seat to rulings against the Trump administration because it failed to follow the rules in making those two consequential policy changes.

“I don’t think [Justice Samual] Alito or Justice [Clarence] Thomas cares about things Roberts cares about,” Weinstein said.

Because the two justices who could most conceivably step into the “swing” position— Justice Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh — are very new to the court, it’s hard to game out just when and how they would embrace playing such a role. For the most part, Gorsuch has positioned himself on the court’s far-right wing. But he has occasionally delivered surprises, like when he wrote a majority opinion expanding LGBT protections this year.

Kavanaugh, while appearing to be less willing to sign on to some hardline dissents, has also not shown significant interest in breaking with the conservative bloc as a whole. For instance, Kavanaugh dissented when Roberts this year voted with the liberals in favor of striking down an abortion restriction that was a replica of a law the court had ruled unconstitutional just a few years prior.

“It’s possible that the new median will have the same institutional interests, but I see no evidence of that generally, so I think we’re in for a wild ride,” Friedman said.

Because he remains the court’s chief, Roberts still has some influence over the rest of the court. He gets to assign opinions, which may help him still guide the court towards opinions that take a more incrementalist approach to delivering decisions that are nonetheless conservative victories.

Serious threats from Democrats that they’re considering restructuring the court could strengthen Roberts’ arguments for the justices taking a more minimalistic approach.

“Even if he was not the swing vote in the same ways, he has an audience in his colleagues who are willing to work with him to find ways to decide cases in ways that are least inflammatory as possible to people who disagree with results,” Arthur Hellman, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, said.

But if Democrats don’t control the Congress and the White House, Hellman said, “then at the point, Roberts loses some of his leverage in trying to moderate.”