This article was originally published at ProPublica, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom.

A year after persuading Texas lawmakers to buy millions of child identification kits that had no proven record of success, a businessman with a troubled history found an in with the state’s attorney general.

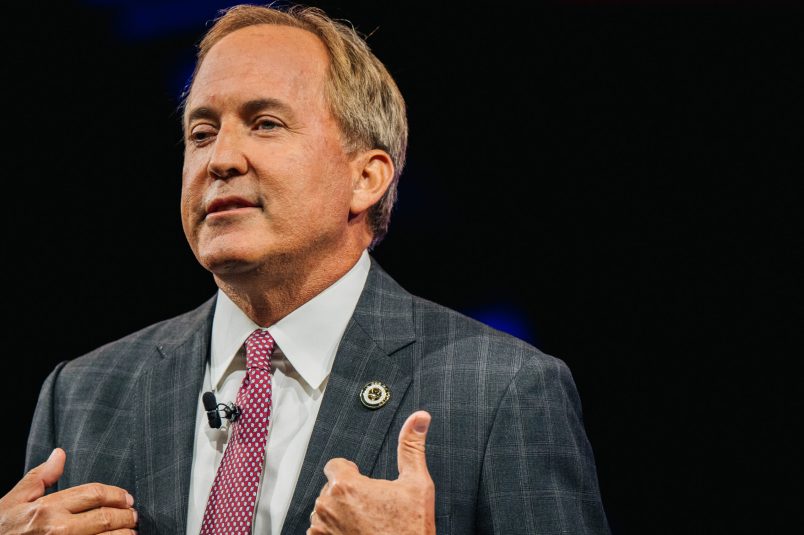

Last fall, Kenny Hansmire was tapped by Republican Attorney General Ken Paxton to be part of a coalition to combat opioid abuse that Paxton declared would “be the largest drug prevention, education, abatement and disposal campaign in U.S. history.”

Riffing off the name of a popular book about Texas football, Paxton announced the Friday Night Lights Against Opioids coalition and pilot program. The initiative would distribute 3.5 million packets at high school football games that contain a powder capable of destroying opioids when mixed with water.

Paxton didn’t provide a price tag for the effort or explain Hansmire’s exact role, but he said a partnership with the businessman’s National Child Identification Program would be important to the program’s success.

A former NFL player, Hansmire has persuaded leaders in multiple states to spend millions of dollars purchasing inkless fingerprinting kits on the promise that they could help find missing children. Texas alone allocated $5.7 million for kits over the past two years. An investigation published last month by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune found little evidence of the kits’ effectiveness and showed that the company exaggerated missing child statistics in its marketing.

The investigation also revealed that Hansmire has twice pleaded guilty to felony theft and was sanctioned by banking regulators in Connecticut in 2015 for his role in an alleged scheme to defraud or mislead investors.

Paxton has been a key ally for Hansmire. In 2020, he signed a letter to then-President Donald Trump urging him to get behind ultimately unsuccessful legislation that would approve the use of federal money to pay for the child identification kits. Hansmire later honored the attorney general at a Green Bay Packers game for his support.

For the opioid initiative, Paxton worked to connect Hansmire with Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar, who oversees the distribution of hundreds of millions of dollars the state is set to receive after settling lawsuits with pharmaceutical companies over their roles in the opioid crisis.

Paxton discussed the initiative with Hegar, asking him to speak with its leaders, including Hansmire. On multiple occasions, Hansmire “called Comptroller Hegar to ask for funding for the Friday Night Lights program,” said the comptroller’s spokesperson, Chris Bryan.

Hegar, a Republican former state legislator who served with Paxton in the Texas Senate, declined to entertain Hansmire’s requests and explained that funding decisions will follow a formal approval process that is still being developed, Bryan said. He did not respond to additional questions.

Hansmire’s financial stake in the opioid initiative is unclear. He did not respond to questions about his role or about his requests for funding from the comptroller. He has previously defended himself and his company, asserting that the fingerprinting kits have made a difference in missing child investigations and that he resolved his financial and legal troubles.

Over the years, Hansmire has successfully leveraged his relationships with professional and college football teams in promoting his fingerprinting kits, honoring allied lawmakers and attorneys general at high-profile events such as football games.

While unveiling the opioid program last October, Paxton stood flanked by Hansmire and other former NFL players. Among them: NFL Hall of Famers Mike Singletary, who played for the Chicago Bears, and Randy White, a former Dallas Cowboy. White later participated in the launch of a similar program in Delaware alongside the state’s lieutenant governor. And last month, Mississippi’s attorney general announced the distribution of 500 free “Family Safety Kits.” Each included a child ID kit from Hansmire’s company and a drug disposal packet, which was provided by North Carolina-based DisposeRX. The company, which is also involved in the Texas and Delaware programs, lists Hansmire’s National Child ID Program as an official partner on its website.

Neither Singletary nor representatives for White or DisposeRX responded to requests for comment.

Paxton also did not respond to multiple requests for comment and to detailed questions from ProPublica and the Tribune. The news organizations requested records from Paxton’s office that could show the cost of the opioid initiative, the scope of the work and the breakdown of compensation for the companies involved. In response, the attorney general’s office released some emails, including one that contained an August 2022 letter from Paxton to Hansmire proposing to partner on the initiative. The office has fought the disclosure of other records that include communications with a lawmaker about potential legislation and claimed that it has no record of written agreements or expenditures related to the Friday Night Lights Against Opioids program.

Last month, the attorney general became one of only three state officials in Texas history to be impeached. He has been temporarily suspended while he awaits a trial in the Texas Senate on charges that include bribery, conspiracy and obstruction of justice. (Those charges are not related to the opioid program.)

The impeachment vote in the Texas House was the culmination of a probe by the lower chamber’s General Investigating Committee. In a memorandum, the panel said the inquiry was initiated by Paxton’s request for $3.3 million to cover a negotiated settlement he announced in February with four former top aides.

Those aides sued Paxton in 2020 under the state’s whistleblower law, arguing that they were illegally fired after reporting their boss to the FBI for alleged misdeeds, including bribery and leveraging the power of his office to help a political donor.

Paxton has denied wrongdoing and has dismissed his impeachment as politically motivated.

“Slower Approach”

The week after Paxton announced the proposed settlement of the suit against him, state Sen. Donna Campbell, a New Braunfels Republican, filed a bill that would transfer $10 million to the attorney general from the opioid settlement fund.

Also a supporter of Hansmire’s, Campbell authored legislation in 2021 that led to the approval of $5.7 million to provide child ID kits to elementary and middle school students across the state. (State lawmakers had been set to approve additional money this year to purchase kits, but budget negotiators nixed the funding following publication of the ProPublica-Tribune investigation.)

In this case, Campbell’s bill would direct funding to Paxton that he could use “for the purpose of prevention, education, and drug disposal awareness campaigns to include providing at-home drug disposal kits and abatement tools for children- and youth-focused populations across this state.”

A new 14-member council led by Hegar is responsible for doling out the bulk of the opioid settlement funding, though lawmakers can allocate some of the money through legislation.

A week before Campbell filed her opioid bill, Hansmire’s longtime business partner, Mark Salmans, registered a new company with the state called Friday Night Lights LLC. Little information is publicly available about the company.

Campaign finance records show Salmans has donated $6,500 to Paxton and his wife, state Sen. Angela Paxton, since late 2019. That includes a $1,000 donation to the attorney general the week after the Friday Night Lights Against Opioids announcement. He has not donated to Campbell, according to records from the same time period. Salmans and the Paxtons did not respond to questions about the new entity or their roles in the program.

Campbell also didn’t respond to questions. Her bill, which died in committee, came after both Paxtons publicly criticized Hegar for being slow to distribute the opioid settlement money. Neither Paxton mentioned the Friday Night Lights Against Opioids initiative while doing so.

“My main concern is that if we wait to use that money, we’re missing the opportunity to help people that need the help and we’re missing the opportunity to really save lives,” Ken Paxton said at a hearing in response to questions from Campbell less than two weeks before she filed her bill. Hegar has defended the pace, noting that the nature of the council’s work is unprecedented and that it needs to establish a clear, fair and transparent process to get the money out.

At a legislative hearing in late January, Hegar pointed to the sweeping corruption scandal that plagued the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas during its first few years as a reason to ensure a more deliberate process. The state agencycame under fire a decade ago for doling out tens of millions of dollars in grants to politically connected applicants through a process that lacked proper scientific review. The scandal, which raised concerns about conflicts of interest and lax oversight, resulted in various resignations and reforms.

“The point is, we’re taking a slower approach to make sure we get it right,” Hegar told Angela Paxton. “That entire board was wiped away because the process that was put into place was not very thorough, and all of their reputations were tarnished.”

Opioids and Missing Children

At the October news conference where Paxton announced the Friday Night Lights Against Opioids initiative, Hansmire explained that it would employ the model pioneered by his child identification company, which got its start by distributing kits at college and professional football games.

He also linked the initiative to his child identification company by repeating the incorrect statistic he’s used to promote the company’s fingerprinting kits. Hansmire asserted that, “out of 800,000 children that are reported missing every year, 200,000 of those have an opioid issue.”

He didn’t cite a source for the figures, but they appear to come from an old Department of Justice study that was co-authored by David Finkelhor, the director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire. Finkelhor previously told ProPublica and the Tribune that the 800,000 figure Hansmire was using from the 24-year-old study was no longer accurate and overstated the scale of the missing children problem, in part because it included children who were missing for benign reasons such as spending the night at a friend’s house or coming home late from school. Using the inflated and outdated figure to then suggest that a quarter of those children have opioid-related problems is simply wrong, Finkelhor said.

The Department of Justice study estimated that 292,000 children who ran away or were kicked out of their homes in 1999 were “using hard drugs.” Finkelhor said the study referred to anything aside from marijuana — not just opioids — as a hard drug. He said he is not aware of anyone who formally tracks “opioid issues” among missing or runaway children.

Experts say that beyond being premised on incorrect statistics, the promotion of disposal packets as a solution for the opioid epidemic is a misguided use of resources, in large part because prescription opioids can be safely disposed of in multiple ways. According to the Food and Drug Administration, the best way to dispose of most medications, including opioids, is to drop them off at a drug take-back site. If that’s not an option, they should either be flushed down the toilet or be thrown in the trash, depending on whether they are on the FDA’s flush list.

Pushing disposal packets is a good way for a politician or legislator “to appear to be addressing the opioid crisis without actually doing anything that would upset industry,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, medical director for the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University.

Paxton and Hansmire didn’t respond to questions about the effectiveness of the packets. But Paxton said during the October news conference that it was his “hope and prayer that this program will aid in fighting the opioid epidemic that has claimed far too many young lives across our great state.”

The attorney general’s original plan was to distribute the 3.5 million disposal packets at high school football programs across Texas in the latter part of last year. But Brian Polk, chief operating officer of the Texas High School Coaches Association, said the inaugural distribution was smaller than envisioned.

Polk, whose organization partnered with Paxton on the initiative, couldn’t remember exact numbers but said in an interview that about 10 school districts received 3,000 packets each. A much larger distribution is expected this fall, but plans are still being finalized, Polk said.

Paxton did not respond to questions about Polk’s comments or whether unsuccessful efforts to tap opioid settlement money contributed to the smaller-than-planned distribution.