Gabriella Cázares-Kelly thought she knew what she was in for when she took over this year as Pima County recorder, leading the office that oversees several aspects of elections. She had a dedicated staff working under her, and she also hired a former recorder from Maricopa, Arizona’s largest county, to help her navigate her early months in the role.

But with the deluge of election-related legislation being introduced in the statehouse, Cázares-Kelly realized she would need another staffer just to follow the proposals the lawmakers would be considering. So she hired a legislative tracker.

“We were getting them in chunks at a time where we simply could not read all the bills while we’re trying to maintain regular operations,” Cázares-Kelly told TPM, recalling some days on which 10, 15 or even 20 new measures would drop.

“The tactic, overall, to introduce so many bills at once is designed to overwhelm election officials here in Arizona,” she said, noting that smaller, more resource-strapped counties wouldn’t have the resources to bring on an additional staffer, as she did, just to track the bills.

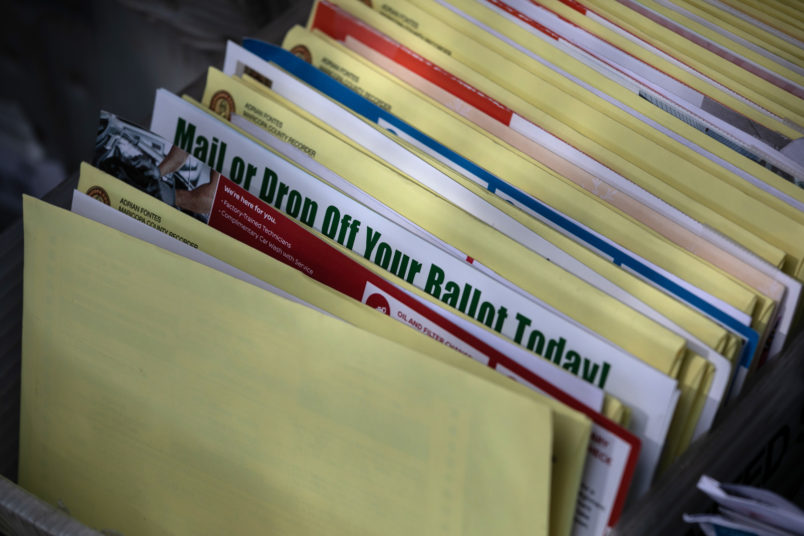

Arizona is no stranger to fights over ballot access. As the state slowly turned purple, its Republican Party has jerked further to the right as its grip loosened on the dominance it once had over the state. When those trends collided with President Trump’s unprecedented effort to overturn his defeat in the Grand Canyon state — an effort fueled by his lies about mail ballots — the state’s well-established system of mail voting became a prime target for legislative attack.

What had previously been a fringe effort to kneecap the state’s mail voting system is now an all-consuming flashpoint in the state Capitol.

“The skepticism about the early voting has been there for some time from some of the legislators,” said Helen Purcell, a Republican who served as the top election official in Maricopa County until January 2017. “We have some new legislators … but what happened in this election and the Trump issue and so forth, it has emboldened some of them to be strident about what they think they want done.”

Republicans’ margins in the statehouse now are tighter than they had been during those past pushes.

“The previous attacks have failed because there is such pushback from voters of all stripes,” Arizona Secretary of State Katie Hobbs, who served in the legislature including as senate minority leader, told TPM.

“What we are seeing this year, especially, is a Republican majority that has the closest margin that there’s been in the legislature in decades,” she said. “And the majority of that majority being dissatisfied with the outcome of the election and simply doing everything that they can to make it harder for people to vote.”

Arizona’s expanded mail voting system put the state’s election administrators in a good place to prepare for the pandemic last year, as mail balloting had already been embraced by large crosscuts of the Arizona electorate; eighty percent of ballots were cast that way even before the COVID-19 outbreak took hold.

“This was widely accepted and preferred by Republicans, Democrats, city voters, rural voters, whites, people of color — it was something that majorities of all demographics were using,” said David Becker, a national elections expert who has advised Arizona’s Democratic secretary of state. If the bills gaining momentum become law, mail voters will be subject to more onerous ID requirements, and other protocols that will make the process of receiving and sending mail ballots more cumbersome.

Well before 2020, there were elements of Arizona’s Republican party that pushed false narratives about mail voting, former election officials told TPM, while other GOP lawmakers stopped short of giving their vocal support to the practice — even if they used mail voting themselves and their campaigns built turnout operations around Arizona’s system.

It was normal for every session to bring about some attempt to tweak the process. But legislators usually gave some deference to election officials, who helped stall or water down the most harmful bills, according to Amy Chan, who was the election director under Republican Secretary of State Ken Bennett. The Voting Rights Act — before the Supreme Court gutted it in 2013 — also acted as backstop by requiring that Arizona get federal approval for changes to election procedures, Chan said.

With the Supreme Court having already opened the floodgates, Trump’s 2020 rhetoric helped turn a wave of restrictive proposals into a tsunami. The legislature introduced more than 140 election-related bills this year (though not all of the proposals were restrictive) — more than doubling the count in 2020.

“A wide swath of legislators decided they wanted to play in the field of elections,” leading to the “inordinate” number of bills in the state, said Jennifer Marson, executive director of the Arizona Association of Counties.

“Everybody wanted to be able to go back to their constituents and say, ‘I solved X problem.’ Whether X problem was real or not, from our perspective, is irrelevant. They wanted to be able to take that message back to their constituents.”

Some of the old guardrails have worked again, with many of the measures that would have made the most sweeping changes to Arizona’s elections having stalled out. Among the proposals that haven’t moved forward was one that would have let the legislature reject the results of an election even after they had been certified by election officials.

But the proposals that are still alive would significantly diminish the ease with which Arizonans can currently vote by mail.

Among the most contentious bills still kicking is one that undermines Arizona’s permanent mail voting list. This is the third time the bill — which would purge voters from the list after they didn’t participate in a certain number of elections — has been introduced in the statehouse, and there are indications it is now getting more buy-in from mainstream Republicans. Its supporters were able to flip the vote of a key Republican senator, reviving the bill after it had failed last month on the Senate floor.

A bill that creates more stringent ID requirements for mail voters was also recently approved by the Senate last week and is now in the House. Rather than using signature verification, voters would face a more stringent ID mandate in mail voting, which will likely require at least some voters to make paper copies of IDs or send in other documents to prove their identity.

The proposal is raising a whole host of privacy concerns, in addition to the prospect that it will make the mail voting process more cumbersome for both voters and administrators.

And though it hasn’t made it out of the Senate yet, voter advocates are also keeping an eye on legislation that would shorten by five days the window of time in which voters would have to return their mail ballots. In addition to requiring that ballots be postmarked by the Thursday before Election Day — a mandate that will complicate the canvassing work of election officials — the bill’s shortened return window will also undermine efforts to make sure Native voters in far-flung tribal communities are able to get their ballots in.

Arizona’s Republican governor, Doug Ducey, could provide a check on legislation restricting voting rights, but whether he will do so is still an open question. A spokesperson for Ducey told TPM that he doesn’t comment on pending legislation, but the governor defended Arizona’s system when Donald Trump attacked it in 2020, outraging the state’s Republican Party. He’s also angered some Republicans with his COVID-19 restrictions — including Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita (R), a driving force behind several proposed voting restrictions who in January referred to Ducey’s COVID-19 emergency declaration as a “dictatorship.” (Ugenti-Rita and other prominent Senate champions of restrictive voting proposals did not respond to TPM’s inquiries.)

“What will the ninth floor do if this issue gets to them?” wondered Marson, of the Arizona Association of Counties, referring to the governor’s office. “There’s so many things to factor in that have never existed before.”

Correction: This article initially misstated the tenure of Helen Purcell, the former recorder in Maricopa County, Arizona. She served until January 2017, not 2019.