This article was originally published at ProPublica, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom.

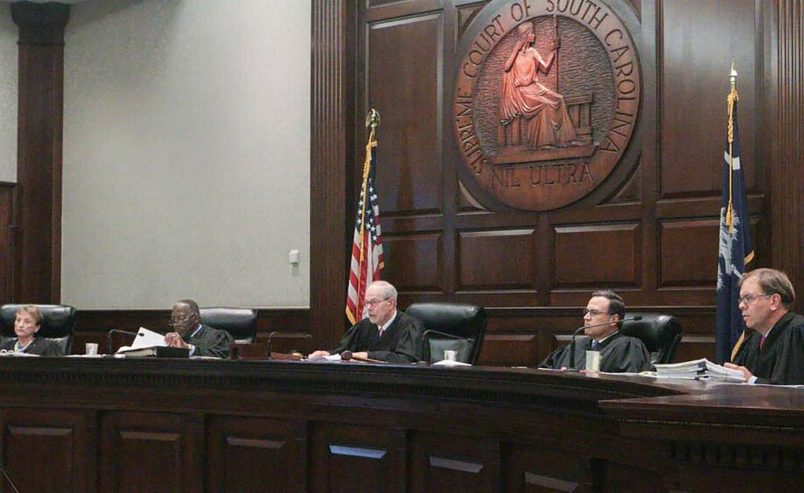

When attorneys arrived for oral arguments in South Carolina’s high-profile abortion case last fall, state Supreme Court Justice Kaye Hearn took her seat up front, a ruffly white shirt beneath her black robe, the only woman on the dais. With piercing blue eyes, she scanned the courtroom.

A sea of white men jammed one side of the room. Before them, at a wooden table, sat three male attorneys there to argue in favor of the state’s law banning abortion after about six weeks of pregnancy.

On the other side of the room, a group composed mostly of women crowded benches behind a female attorney who had challenged the law.

Even in these polarized times, the starkness of the divide stunned Hearn.

South Carolina’s high court was among the first to hear an abortion law challenge after the U.S. Supreme Court released its Dobbs v. Jackson decision last June, overturning the country’s landmark abortion rights case Roe v. Wade and kicking the combustible issue to the states. Hearn knew the nation was watching. But she didn’t anticipate that the arguments about to begin in that divided courtroom would contribute to an even starker gender divide on the court where she sat.

Three months later, on Jan. 5, the justices struck down the deep red state’s abortion law. By a 3-2 vote, the majority ruled that the law violated the state’s constitutional right to privacy. Hearn wrote the lead opinion, a capstone of sorts given she had reached the mandatory retirement age of 72.

While abortion rights supporters rejoiced, the ruling outraged the General Assembly’s new supermajority of Republicans, many of whom derided her as an activist jurist. They also saw an opening.

In South Carolina, unlike all but one other state, the legislature alone selects judges. And in just a few weeks, they would vote on Hearn’s replacement.

The three candidates, who’d been put forward by a legislative commission, were all widely respected judges on the state Court of Appeals: one man, two women. Both women had longer tenures on the state’s second-highest court than the man. One had beat him before: She’d won over legislators in the 2014 race for her appeals court seat. He arrived three years later.

It wasn’t certain how any of the candidates might rule on an abortion case. (Before Dobbs, federal courts handled nearly all abortion law.) Nor were the candidates’ political views obvious; state judicial canon strictly forbids commentary on controversies or issues that may come before the court.

But before lawmakers could cast their votes, the overwhelmingly male lot of Republicans rallied behind the male candidate, Gary Hill, ultimately creating the only all-male state Supreme Court in the nation.

“It’s all kind of clandestine, cloak and dagger,” said Barbara Rackes, president of SC Women in Leadership, which works to boost women’s influence and representation in the state. “It was not happening in the committee chamber or on the floor. The decision was made in the backroom.”

As Republican lawmakers coalesced behind Hill, people who know the female candidates described them as grappling with intense pressure to withdraw quickly. Neither judge responded to requests from ProPublica for comment. Hearn said she had spoken to both, and they were “very hurt by the process.”

Democratic Rep. Beth Bernstein, an attorney on the state House Judiciary Committee who also chairs the House women’s caucus, called outrage over the abortion decision “the reason we don’t have a Supreme Court justice who is a female.” A contingent of lawmakers “felt a woman couldn’t vote on this issue objectively maybe, which is mind-boggling to me because its impact on women is most substantial.”’

Justice Hearn agreed: “I do think the fact that he was a man was important to some of them.”

Republican Rep. Micah Caskey, a former prosecutor, said he supported Hill because of the acumen he witnessed during Hill’s 13-year tenure on the circuit bench. But he said the abortion ruling, so fresh at the time, motivated other Republicans.

“There are certainly people who voted for Judge Hill on the basis of their understanding of where he would be on abortion,” Caskey said.

Following Dobbs, South Carolina’s race underscores the newly starring role of states’ top courts in determining abortion access — and the resulting impact on who gets chosen to serve on them. The machinations have left many in the state fearing increased politicization of their already unusual judicial selection process, which gives near-total power to politicians.

Consequences of an all-male high court are especially pronounced in this state, which consistently ranks at the bottom of lists measuring women’s well-being.

Women there already have among the weakest representation in the country. Only 14.7% of state lawmakers are women. The house speaker and pro tem are men. Ditto for the senate president. The governor is a man. (The lieutenant governor is a woman.)

Only two women have ever served on the state’s Supreme Court.

And now there are none.

Stronghold of Men

All three judges who vied for the seat are highly regarded in legal circles across the state. Among them, Judge Aphrodite Konduros brought the most experience.

After almost 15 years on the Court of Appeals, she had written more than 400 opinions, signed on to another 800, and served far longer than the other two candidates. The granddaughter of immigrants, she also had been a family court judge and served as counsel for two state agencies.

Earlier in her career, Judge Stephanie McDonald left a law firm during a very difficult pregnancy, then started her own firm so that she could best raise her daughter. She persevered to become a successful trial attorney, circuit judge and appellate judge — the seat she took after beating the male candidate she would face again for the Supreme Court post.

But the women also worked in a state long known for its “good old boy” culture and the generational legal legacies that elevate certain men in the halls of its courthouses — and in its Statehouse. These men enjoy long-standing relationships with their fellow male attorneys in the legislature, which, in turn, holds near-total power over electing judges.

A key gatekeeper in the process is the state’s Judicial Merit Selection Commission, a group comprising mostly legislators who screen candidates and choose up to three they deem qualified for each open seat. The entire General Assembly then votes on them.

At a commission hearing in November to interview the candidates, then-Chairman Luke Rankin, a powerful Republican senator, welcomed Hill with familiarity.

“Obviously, I know you. We were in law school together. I think maybe I’m substantially older than you, but we were there at similar times. But your father and my father were contemporaries,” he said before lauding Hill’s late father, a former president of the South Carolina Bar whom he described as legendary.

“I remember meeting him when you and I were punks at Hilton Head with the thought of law school perhaps ahead of us,” Rankin said.

Hill, who can trace his family lineage in South Carolina back at least to the 1850s, also clerked for former 4th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge William Wilkins, an esteemed figure in the state’s judicial circles. After clerking, Hill went on to join his father’s law firm, and they later opened a firm together.

Yet, early on, it appeared at least one of the women had a decent shot, especially in a contest to replace the only female justice. Hearn and others figured Konduros was the likely front-runner. Although quick to praise all three judges, she called Konduros “one of our superstars.”

Then, on Jan. 5, came the abortion ruling.

At the time, a new far-right group freshly empowered by gains in November’s election had grabbed hold of the party’s right flank on abortion. Called the Freedom Caucus, its 18 members were determined to get a justice who would uphold a future abortion ban. None of the members ProPublica contacted would comment.

Joining with other Republicans, they coalesced around the male judge, leaving many to wonder if that support stemmed from two intermingled factors: abortion and gender.

“Nothing in the judicial record of the two female candidates seemed to be at issue. It was entirely their gender that disqualified them,” said Lynn Teague, a lobbyist for the League of Women Voters of South Carolina.

But Republican lawmakers insist they saw important differences among the candidates.

Rep. Anne Thayer said far more people in the legal community in her district, which sits in a conservative part of the state not far from where Hill lives, contacted her to praise him. Konduros was also seen as Hearn’s close friend and perhaps hand-picked successor. “I think that probably hurt her a lot” due to Hearn’s opinion in the abortion case, Thayer said.

McDonald, meanwhile, had practiced law with Republican Sen. Sandy Senn, who opposes the strictest abortion bans, creating the perception she might be like-minded, several lawmakers said.

Republican Rep. Sylleste Davis said of her vote for Hill: “I’m focused on the person I think is best for the job.”

She was among a group of lawmakers who met privately with the candidates to question each of them. She said she came away most impressed by Hill: “I could tell he was very thoughtful about every question and every answer.”

Republican Rep. Matt Leber had a similar experience meeting with the three candidates after the abortion ruling. He said Hill “can quote the Federalist Papers and all this, and he just outshined the other two.”

McDonald came across as “completely capable,” he said. Konduros did as well, although Leber said she came across as a bit more “aggressive” and “abrasive.” That wasn’t a deal breaker for him, he said, but given all three candidates were impressive, “every little thing counts.”

For many women, that observation may echo expectations that they soften their edges so men don’t find their assertiveness off-putting. One former judge said this can be especially challenging for female judges who must control their courtrooms — and the men who appear before them — to ensure fair and proper proceedings.

Some Republicans also said that Hill struck them as the most reliably strict constructionist — meaning he will interpret the literal meaning of language when it was written — something of key importance given they had blasted the abortion ruling as judicial activism.

But when ProPublica asked several of them to name a specific appeals court case in which Hill ruled in a way that made him appear more of a strict constructionist than either female judge, none of them did.

Intense Pressure

On Jan. 17, mere hours after the judges were allowed to begin seeking vote pledges from lawmakers, the two female candidates bowed out. The move shocked some observers, who accused Republicans of backroom deals and partisanship that pushed the women to quickly withdraw.

“That would be like me running for Senate, and then on the day of the election I pull out 15 minutes before the polls open,” said Sen. Senn, the Republican who practiced law with Judge McDonald until a decade ago.

In South Carolina, judicial candidates cannot seek commitments — nor can lawmakers give them — until the Judicial Merit Selection Commission issues its final report regarding judges’ qualifications. It released that report on Jan. 17 at noon.

The House GOP caucus met that morning. Several legislators told ProPublica that one of the female judges began communicating to close supporters that she was withdrawing around that time, before any votes could be legally offered or tallied.

At 4:40 p.m., the commission’s counsel emailed members notifying them that both women had formally withdrawn, lawmakers said.

It is customary for judicial candidates who lack support to politely back out before the legislature formally votes. But that doesn’t typically happen before at least a few days of jockeying once everyone can discuss pledges.

“You could not have run around the House floor fast enough” to solicit votes before the two bowed out, Teague said.

Senn soon publicly voiced allegations that she’d heard her colleagues in the Republican House caucus had conducted a secret poll before they were allowed to pledge commitments — then used the result to force the women out.

Republican Sen. Katrina Shealy, once the only woman in the Senate, said pressure on the women meant that anyone who wasn’t in the House caucus meeting, particularly senators and Democrats, had almost no time to pledge — and try to spread support — for them. She said that she didn’t doubt Hill’s talent but was angry the women dropped out without more of a fight. “We had two qualified women running and didn’t have an opportunity to vote for them,” she said.

Citing caucus confidentiality, nearly all House Republicans reached by ProPublica refused to address whether they took a poll that morning. Speaker Murrell Smith declined to be interviewed, although a spokesperson said the speaker maintains the allegations are “baseless.”

The few Republicans who would discuss the caucus meeting denied wrongdoing.

“I don’t think that there were any lines that were crossed or anything like that,” said Republican Rep. Neal Collins, who sits on the House Ethics Committee. “Nobody was forced into commitments. Nobody asked for any commitments. Nobody made any commitments.”

Caskey, who was vice chair of the Judicial Merit Selection Commission at the time and is now chairman, is a former prosecutor who also sits on the House Ethics Committee. He wouldn’t elaborate on the caucus meeting other than to say they discussed the race, but he noted that decisions made there are not binding regardless.

Yet, even to him, the women’s withdrawal came unusually early: “I can’t recall any other instance of a judge in any race or any candidates — certainly not both, or certainly not two of three candidates — getting out of the race on the first day.”

As the clock ticked on Jan. 17, Hearn began receiving messages that the women lacked support.

“My heart sank,” she said. “I was devastated.”

A few days later, Senn blasted her Republican colleagues for pushing out two qualified women. “We know it isn’t really about the smartest judge or the best candidates,” she told the Senate. “It is about who you know will demand forced birth.”

In early February, 140 of the state’s 170 legislators voted for Hill, the only candidate left. Eight voted against him; three voted present. None of the five women in the 46-member Senate cast a vote in his favor.

Shealy was among those who voted present. “It was a statement,” she said.

History Repeating

Back in 1999, Hearn was elected the first female chief judge of the state appeals court on the same day the first and only woman on the Supreme Court was elected its chief justice. A decade later, Hearn joined Justice Jean Toal on the high court.

As other states set records for electing female justices, Toal and Hearn remain the only two women to reach South Carolina’s highest court. Many other Deep South states aren’t faring much better. Mississippi’s Supreme Court has one female justice and eight males. Louisiana has one woman and six men.

Alabama and North Carolina each have two female justices. Neighboring Georgia comes closer to a representative court, with four females and five males. Tennessee is a notable outlier, with a high court comprising 60% women. However, the court is small — only five justices — and one of its three women has been on the bench for 27 years.

In South Carolina, women are better represented on the lower court. Half of its Court of Appeals judges are women. Yet, the glass ceiling to the top court remains remarkably shatterproof.

“The stakes are higher there. That body is the checks and balances for the legislature,” Hearn said from her chambers in Conway, a county seat about 15 miles inland from Myrtle Beach. (Retired justices continue to write opinions and do other work on cases they heard previously.) She wore a pale pink suit to signify the importance of women on the bench.

Jessica Schoenherr, who teaches about America’s judicial system at the University of South Carolina, examines challenges to diversifying the bench. She called South Carolina unique in going from at least one woman on the court to none. “They went backward, and across the world, that almost never happens,” she said.

Agree with it or not, Hearn’s ruling that overturned the six-week ban was informed by her personal knowledge of the way a woman’s body works and when she realizes she’s pregnant. “I do think women have an understanding that this business of six weeks” is “just impossible,” she said. “It’s not workable.”

As she looked out over the divided courtroom that day back in October, she was well aware of the perspective she brought to the case at hand.

Quizzing a male attorney for the male governor, she asked about a privacy provision in the state constitution that some legal experts had argued protects the private and personal right to abortion. “What could be more personal than a woman’s decision to have an abortion?” she asked.

The lawyer began to invoke Roe v. Wade, the U.S. Supreme Court’s now-defunct 1973 decision that guaranteed a right to abortion.

She interrupted: “I’m asking you. I know you’re not a woman, but what could be more personal than that decision?”

“Your honor, there could be any number of things that could be more personal…”

She cut in: “Name me one.”

In the months since the South Carolina court’s explosive ruling, Republicans have repeatedly tried to pass a new abortion ban.

Just this week, the Senate’s president tried yet again, pushing for a vote on a bill the House passed that would prohibit the vast majority of abortions after conception. But he couldn’t overcome a substantial obstacle: the Senate’s five women. The three Republicans and two Democrats banded together to control debate until the chamber voted to scrap the bill for the session, leaving the House and Senate at an impasse.

If the two chambers ever do agree on a new abortion law, one thing is clear: It will almost certainly reach the Supreme Court. And this time, the women gathered in its stately courtroom would face a bench filled with men.