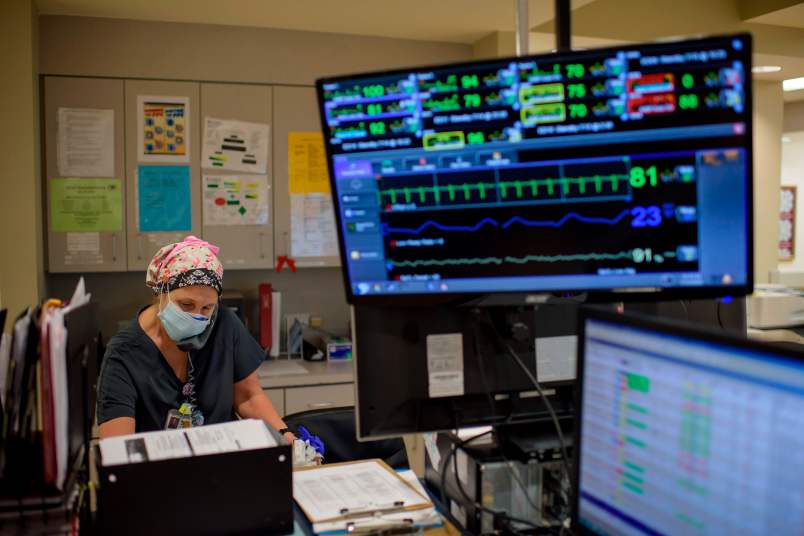

Leslie Porth, a senior vice president at the Missouri Hospital Association, began a statewide conference call on July 15 with an apology.

Just two days earlier, the Trump administration had sent a letter to hospital administrators, telling them that by the 15th, they would need to stop submitting COVID-19 data to the CDC’s National Health Safety Network — a years-old survey backed by some of the government’s top epidemiologists.

Instead, they were told to begin sending it to TeleTracking, a private vendor based in Pittsburgh that had been working with the Department of Health and Human Services.

“We were not aware this was coming, nor were our state or many of our federal partners, to be honest,” Porth explained to the assembled hospital representatives who make up MHA’s membership. “It was an unexpected change, and without appropriate time to transition from one system to another.”

Local officials and hospital representatives later complained that HHS, which ordered the change, hadn’t briefed them on how the shift to TeleTracking would affect their data entry operations — nor given them adequate time to prepare. The result was widespread chaos.

The TeleTracking survey was formatted differently than the old HHS survey and asked new questions. And the Trump administration was now insisting on daily data entries — a challenge for smaller hospitals where the staff responsible for reporting data took weekends off, and for larger hospital networks in which beds, drugs and other supplies are spread across several locations.

Missouri, whose state public health authorities work with MHA to present public COVID-19 data, experienced a hospitalization data “blackout” that lasted nearly two weeks as a result of the change.

Without accurate data, state and local officials were left to guess if and when they should implement more stringent public health orders, request back-up equipment, or shift resources and patients between hospitals.

What your state's COVID-19 data looks like when the Trump administration switches to a private contractor with basically zero notice: "Hospitalization data from the period of July 13 through July 24 will remain unavailable." (This is Missouri) pic.twitter.com/fNXo0ncVwZ

— Matt Shuham (@mattshuham) July 31, 2020

Other states experienced similar outages, and questions on data quality persist two-and-a-half weeks later.

“It’s as if you bought furniture at IKEA, but the instructions on how to assemble it don’t come with the packaging,” Dave Dillon, a spokesperson for MHA, told TPM of the new survey.

“We sat here for two weeks with our IKEA furniture all over the floor, not knowing what the hell to do with it.”

In a statement to TPM after the publication of this article, HHS acknowledged that “hospitals were not given significant time to prepare for these changes” but said “the Covid-19 response requires that we move quickly, even when more time might be desired.”

“In this case, we had an urgent need to have specific data in order to allocate the remdesivir for that week,” HHS said, referring to the antiviral medication. Even before the abrupt July switchover, the Trump administration had used TeleTracking survey responses to allocate the drug nationwide. “The NHSN product was not able to make rapid changes for needs like this which is what led to the immediate change.”

‘Exactly who is TeleTracking H-H-S?’

The administration’s sudden order that hospitals switch to TeleTracking on just days’ notice left metaphorical IKEA components strewn all over the country.

In South Carolina, which also experienced a gap in hospitalization data, the Department of Health and Environmental Control warned that TeleTracking’s survey asked for a tally of all available beds as one “total” number — seemingly lumping in, for example, psychiatric beds and neonatal ICU bassinets not available for COVID-19 patients.

“As a practical matter, not all of these bed types could be used for caring for adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19,” the state noted in a statement on the DHEC website.

In Idaho, public health authorities warned that “data after 7/15 may not capture all hospitalizations or ICU admissions while facilities transition over to new data submission processes.”

In Missouri, Dillon noted, HHS had initially listed a half-dozen hospitals in its roster that had actually closed — decreasing the state’s response rate when the non-functioning hospitals failed to submit COVID-19 data.

“This is like taking the wing off an airplane in mid-flight and replacing it, and claiming that this is going to make the plane fly even better,” said Christoph Lehmann, director of the Clinical Informatics Center at UT Southwestern. “You have, already, problems with the data quality. This is going to make the data quality worse.”

“If somebody comes in and claims they can hook up to all the county health departments in the country, and says they can do it in 10 days — I want to know what they’re smoking,” he added.

The COVID Tracking Project, which collects local data to paint a national picture of the virus, observed on Tuesday that state-level hospitalization data had become “erratic” in recent weeks.

“It’s clear that technical requirements associated with the new guidelines have caused major problems,” the group reported, adding: “These problems mean that our hospitalization data — a crucial metric of the COVID-19 pandemic — is, for now, unreliable, and likely an undercount. We do not think that either the state-level hospitalization data or the new federal data is reliable in isolation.”

On that July 15 conference call, hospital officials tripped over themselves when MHA staff opened the lines for questions.

“I have not been doing any TeleTracking — I don’t know what TeleTracking we’re talking about,” one caller said, explaining that her hospital’s patients hadn’t been prescribed any Remdesivir.

“Exactly who is TeleTracking H-H-S?” someone else asked later.

Another caller noted she didn’t have back-up staff available to report data on weekends. The CDC system let her submit data from home, but she so far hadn’t been able to do the same via TeleTracking.

“The message coming from the White House is very firm,” responded Jackie Gatz, another vice president at MHA. “They expect daily reports.”

“What are we considering an adult patient?” asked Michael Sayer, a senior director of infection prevention and control at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City. The hospital didn’t have an adult ICU but was caring for patients in their late 20s, Sayer explained.

“I had the exact same question, because they did not specify,” Gatz responded.

An HHS guidance document released last week addressed a few of these questions — but only partly.

When tallying in-patient bed space, for example, hospitals were told to “only consider specialty beds, such as psychiatric and rehab beds, if they are part of the surge workflow and could be used for inpatient needs.” Adult patients, according to HHS, are those “currently hospitalized in an adult inpatient bed who have laboratory-confirmed or suspected COVID-19.” Dillon noted that definition would exclude adults being treated or observed in pediatric beds, therefore skewing representations of hospitalized pediatric patients.

‘A Faceplant’

All the empirical confusion has had a national impact, leaving public health leaders and others with less reliable data on which to make decisions and guide public behavior.

As ProPublica and NPR reported Friday, HHS initially promised to update the hospital capacity numbers “multiple times each day.” Now, the website says the figure will be updated “daily” — even though the last listed update is from July 23. The reports noted erratic jumps in statewide hospitalization data as well as state and federal numbers that didn’t match.

TeleTracking declined to comment for this story and directed TPM to HHS.

Regarding the hospital capacity data on its website, HHS told TPM that “these projections are based on the information we have from those who reported. As more hospitals report more frequently, our projections become more accurate.”

“HHS decided to update the estimates weekly because these projections are based on the data reported to HHS,” the agency’s statement added. “The strongest estimates can be made using the last 7 days of data reporting.”

HHS said data entries through TeleTracking were becoming more consistent, and that while some states and hospital associations have reported “difficulty” with the new system, “[w]hen HHS identifies errors in the data submissions, we work directly with the state or hospital association to quickly resolve them.”

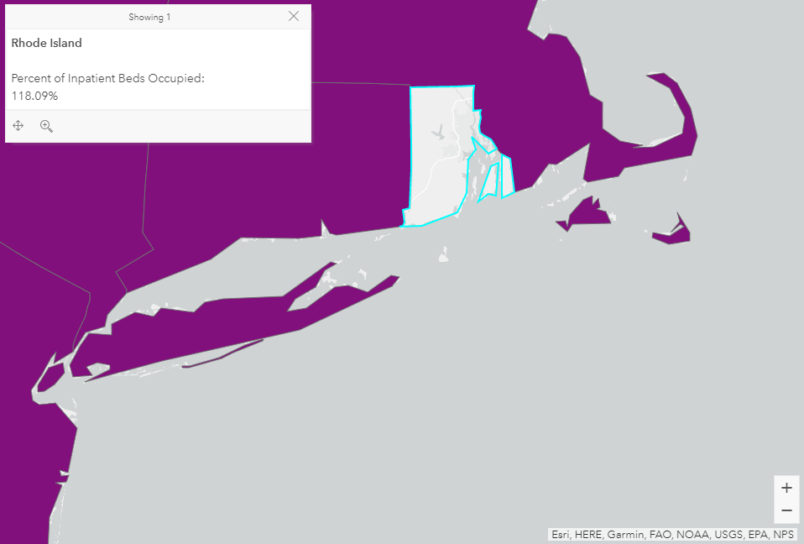

But “difficulties” remain: Ryan Panchadsaram, a former Obama administration deputy chief technology officer, noted on July 23 that the HHS website asserted that 118% of Rhode Island inpatient beds were occupied despite few COVID hospitalizations in the state — an enigma that remained as of Monday.

A spokesperson for the Rhode Island Department of Health told TPM that, contrary to the federal government’s numbers, “we have 2,433 operational beds and 1,893 of them are occupied.”

Ultimately, Dillon told TPM, officials in Missouri had to make guesses about the “guidance” — “I would do air quotes on this,” he noted — coming from the feds.

“Nothing happens in 72 hours in the federal government,” he said, calling the abrupt change to TeleTracking “a faceplant.”

Missouri took down its hospitalization data for twelve days because it couldn’t be sure the numbers coming from the state’s hospitals — which were reporting to a new system with minimal background training — were accurate.

And that’s the tension at the heart of this latest Trump administration action. While the switch to TeleTracking was purportedly meant to sharpen the national picture of a global pandemic — with necessary information about things like hospital space, drug use and ventilator supply — it did the opposite. As a result of the chaos, the federal government effectively “cut off” local officials’ situational awareness, Dillon said.

Once the TeleTracking shift was official — resulting in days of missing data — Dillon said MHA staff began receiving a “flurry” of emails from concerned citizens, admonishing them for the missing numbers.

“Our response was, well, frankly, we agree — we need this data as well,” Dillon recalled. “But we can’t release data we don’t have confidence in.”

This post has been updated to include response from the Department of Health and Human Services.