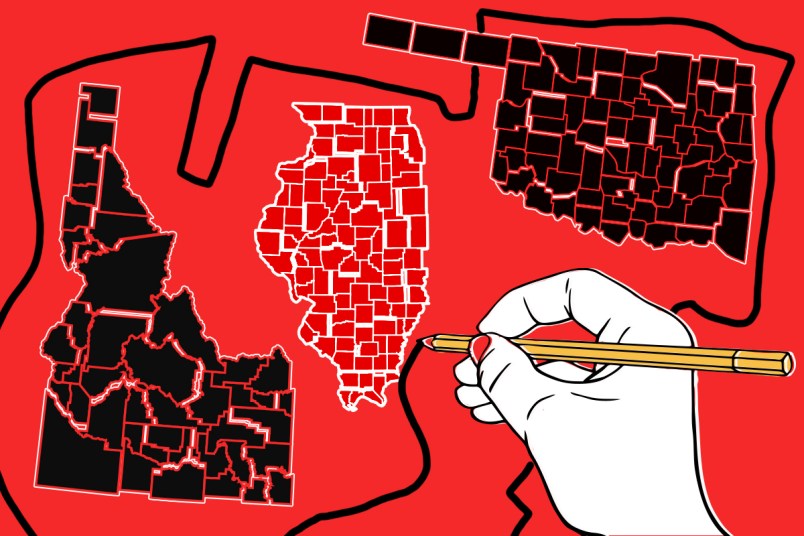

The delays that the pandemic caused to the 2020 census will take the state redistricting process into uncharted territory.

The Census Bureau’s plans to release the count’s data six months behind schedule has put several states at odds with their own deadlines for redrawing their legislative maps. So some are now hinting that they might turn to other data sources as they at least start their redistricting processes.

Such an approach, however, would undoubtedly be challenged in court, adding to what already is expected to be an unprecedented amount of litigation around this year’s drawing of the political maps that will shape electoral power for the decade to come.

“Using anything but the official census data could invite litigation, because you are using data that hasn’t been tested,” said Jeffrey Wice, a redistricting expert and adjunct professor at New York Law School.

So far, only Oklahoma has formally made the decision to use data other than that from the decennial census for its map drawing. But officials in other states are publicly suggesting that they might take a similar route. There could be even more states where such a plan is being discussed privately.

The idea is already getting intense push back from the voting rights and immigrant rights community, who argue that those alternative sources are no substitute for the hard count the decennial enumeration delivers — particularly when it comes to ensuring that marginalized communities get the representation they deserve.

A Timeline Scrambled

Normally, the Census Bureau releases redistricting data by the end of March the year after it conducts the decennial survey. Under that timeline, even states with particularly tight deadlines to finish redistricting still have the spring and early summer to redraw their legislative maps. But the pandemic — coupled with some Trump-era gamesmanship aimed at screwing over immigrant-friendly states — put the bureau severely behind schedule.

Now, full release of the redistricting data — which breaks down the state’s population into extremely granular geographic units, along with those units’ race and ethnicity characteristics — is slated for the end of September. Some states, however, have etched into their constitutions or state laws redistricting deadlines in late summer or early fall. The new timeline for the Census Bureau to deliver data has them in a bind.

A few of those states took proactive steps last year to move back their deadlines, while others are now scrambling to figure out what to do — including whether to look at population data from sources other than the decennial census. Ohio and Alabama have asked federal courts to order the bureau to release the data more quickly. Ohio’s lawsuit was rebuffed in district court in part because the state constitution allows it to consider other data sources.

Looking At Data Sources Besides The Census

The 2020 census delays present a legitimate and serious conundrum for states, particularly the dozen-plus states that have redistricting deadlines before the census data will come out. But the desire by legislatures to maintain control over the map-drawing is also at least partially motivating the decision-making around potentially using other types of data.

Oklahoma lawmakers — who formally okayed the use of data from another source, the American Community Survey, to draw state legislative maps — would see redistricting turned over to an independent commission if they did not finish redistricting by end of the current legislative session. (They’ll wait until the fall to draw Oklahoma’s U.S. congressional districts using the census data.)

Illinois lawmakers would likewise lose their authority to draw the state’s electoral maps if they don’t adopt maps by June 30. The party control of the independent commission that would then take over the line-drawing would be determined by pulling a name out of a hat — specifically, a replica of the hat worn by Abraham Lincoln. Lawmakers in Illinois haven’t officially announced a switch to ACS data — the state Senate Redistricting Chair Omar Aquino told TPM that all options are “on the table” — but they have also signaled that they want to at least draw provisional maps this spring based on non-decennial data to avoid letting map-making be carried out by a GOP-controlled commission.

Elsewhere, the dynamics are a little more complicated. In Idaho, there is some talk of its redistricting commission using county estimates slated for release next month to at least start hashing out which counties will be broken up in the new maps, though that plan isn’t certain. In Oregon, the Democratic Secretary of State Shemia Fagan is pushing in court for the use of population data put together by a local university that will allow the state to stay close to its usual timeline, while the Democratic legislature wants to move the entire calendar back by several months to wait for the fall census release. Use of ACS has come up in recent meetings of Colorado’s new independent commission, while Missouri lawmakers are looking at ACS data as part of a larger anti-immigrant scheme to boost Republican advantages in state legislative maps.

Some of those states have acknowledged that they’ll likely need to come back this fall, after the 2020 census data is released, to make adjustments that account for the discrepancies in the data. But voting rights advocates say even that approach is undermining confidence in the process.

“When a government decides to start adopting lines on a calendar that nobody knows about, using data that people aren’t sure about, using a process where we have no input into, you are guaranteeing people don’t trust the outcome,” Kathay Feng, the national redistricting director for the voting rights group Common Cause, told reporters on a press call Wednesday.

‘Just Buying a Lawsuit’

Voting rights groups are already raising the alarm about the risks that some communities will not get the representation they deserve because the alternative sources are less accurate than the hard count the decennial survey provides.

The American Community Survey, the option being looked at by Oklahoma, Colorado and Illinois, is also done by the Census Bureau. But it is based on sampling, is less granular and includes data collected several years ago.

“The number of inconsistencies shown historically between ACS and decennial data is such that nobody can get away with that, it is just buying a lawsuit,” said Thomas Saenz, the president and general counsel of Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

States could face similar challenges to the other alternative sources being considered, which include commercial datasets put together by private companies.

“The question is, what kind of things might be allowable in their state law,” Kim Brace, a redistricting expert who is working with Illinois and several other states. He said states must be prepared to come back in the fall to modify their maps once the 2020 census data comes out — though that probably won’t be enough to stop a lawsuit from coming.

“Somebody is always going to be mad at what you do. You’re not going to satisfy everybody. And so always be prepared to have a lawyer at your side,” he told TPM.