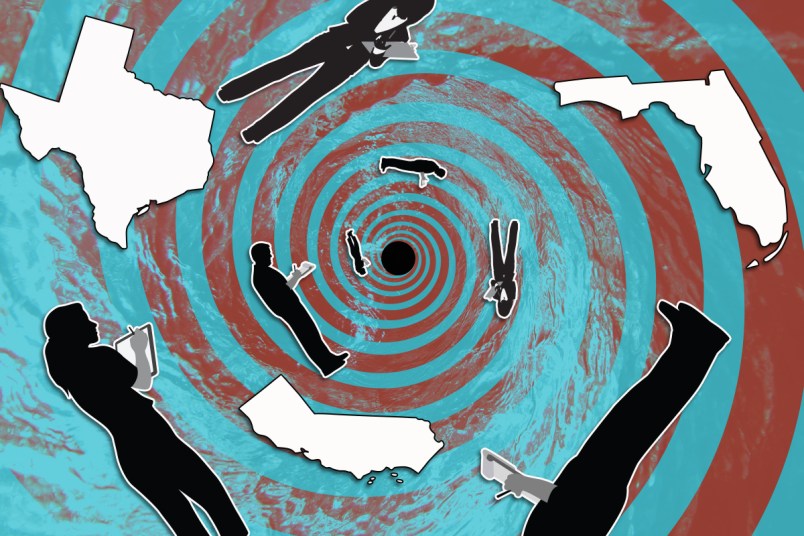

A botched decennial census — a possibility that is looking more likely with the Trump administration’s push to rush the count — will create a nightmare next year and beyond.

In the event the 2020 survey is unusable, there are simply no easy, or even realistic, ways to fix the problem for the aspects of government, and of society, that depend on the census.

“This is going to be a constitutional crisis. It will be a demographic disaster,” William Frey, a census expert at the Brookings Institution, told TPM.

Already, a massive legal fight is ramping up around how the census — which President Trump has hijacked for the purposes of implementing his anti-immigrant agenda — will be used for the doling out political power across the country.

Back when the coronavirus outbreak was taking hold last spring, the Census Bureau asked Congress to extend by four months the statutory deadlines for releasing apportionment and redistricting data — which are typically produced, respectively, at the end of December and March — so that it could have extra time to work around the delays the pandemic caused.

But in recent weeks, the administration has walked back that request, and instead announced that the Bureau will spend one month fewer counting than its proposed pandemic timeline had planned. The reversal appears aimed at making sure Trump is still in office when the apportionment data is produced, so he can try to exclude undocumented immigrants from that count.

Regardless, the move to rush the count is causing grave concerns about its accuracy. As one former Census director recently told Congress, the truncated timeline risked a count that is not “accurate enough to use.”

It’s difficult to even grapple with the consequences of an unacceptably flawed count, given the vast and complicated ways census data are used by both the public and private sector.

But as the Trump administration digs in on its plan to expedite the 2020 count former Census officials, redistricting gurus, research specialists and other experts are beginning to game out what happens if those challenges cannot be overcome.

“There are no easy ways to fix a very inaccurate census,” said Terri Ann Lowenthal, a consultant widely regarded for her census expertise. But she stressed that those mobilized around the success of the census shouldn’t think the towel is being thrown in yet.

“Any alternatives are not as good as having a good first count, there’s no good Plan B,” Denice Ross, who worked as a data expert in the Obama White House and is now at Georgetown’s Beeck Center, told TPM.

Here’s what could be up for discussion if the census falls short.

Not Just How Flawed, But In What Ways Is It Flawed?

The Constitution mandates a decennial census to determine how many House seats each state gets (a process known as apportionment), and states also use census data for the purposes of drawing those districts and their own legislative maps. The data furthermore help decide how $1.5 trillion in federal funding is allocated, and how state and local funding is also doled out. In addition to the government agencies that use it, countless businesses and private research entities draw on the decennial census for their own studies.

Before policymakers and private-sector census users decided what to do with the data produced by the 2020 census, they’ll need to figure out how to assess its quality.

“Everyone expects this 2020 census to not be as good as 2010 for lots of reasons, even before the Trump administration’s politicization of it,” Bill O’Hare, a demographer who’s studied the accuracy of past censuses, told TPM. “I don’t think there’s any consensus for how bad it has to be before rejected, for lack of a better word.”

A key question in the coming months is not just how bad of an undercount a shortened census would produce, but which places and people will be left out of the survey.

Four former Census Bureau directors have called on Congress to tap an independent entity that can develop, ahead of the data’s release, various metrics to determine its quality, and there are other proposals for bringing more transparency into the Bureau’s process of assessing the count’s accuracy.

After data collection finishes, the Bureau usually spends four or five months on post-enumeration quality checks, including programs that happen in the field. The administration hasn’t clearly laid out how those programs will fit into its expedited timeline.

Self-response rates — which currently lag behind the 2010 census — offer an early indicator of potential trouble spots. But, absent additional transparency measures, “it would be really towards March … that people would see that things are really bad,” Frey said, referring to the current deadline for producing redistricting data.

Unlike the congressional apportionment data slated for release in late December, redistricting data are packaged at an extremely granular geographic level and includes characteristics like race and age.

Given the internal benchmarks the Bureau uses, it may know internally before that “whether they are far off the mark,” Lowenthal said. “But they may not be allowed to say so, and I am concerned about that.”

Can The Census Be Redone?

The most ambitious response to a botched census would be to just try to do the census over again. But the 2020 version would have to be horrifically flawed for that to be a serious option, experts told TPM, because of the sheer logistical, technical and financial obstacles involved in conducting the national count.

There are also, right now, legal limits on how such a redo could be used. While federal law contemplates the possibility of mid-decade census, the statute bans such a survey from being used for apportionment or for congressional redistricting. If Congress chose to reverse that statutory prohibition, such a move would still face a constitutional challenge in court.

“I don’t think the courts will be inclined to swap one enumeration for a modestly improved recount a couple years later, just because that creates the incentive to spend a billion of dollars every couple years in order to try to regame the nature of representation,” Justin Levitt, a Loyola Law School professor who worked in Obama’s Justice Department, told TPM.

That being said — costs and logistics aside — Congress appears to have more legal flexibility to redo the census to produce data for its various other uses, including for government funding and for informational purposes.

But the practical challenges can’t be overstated. It would cost billions of dollars, take several years of planning and also a good deal of political will, as states that benefited from a flawed census would likely oppose the move to redo it.

“My sense is the probability [of a redo] is very, very low,” said Margo Anderson, whose book “The American Census: A Social History” covered Congress’ rejection of the 1920 census.

Are States Stuck With the Bad Data For Drawing Their Maps?

When the Bureau announced at the beginning of the COVID outbreak that it wanted until late July 2021 to release the count’s redistricting data, it sent states scrambling to rework their own decennial redistricting calendars. Some states have elections in 2021 that typically require them to finish up redistricting by early summer.

Despite the Trump administration’s reversal on the extension request, that scrambling continues, according to New York Law School adjunct professor Jeff Wice, especially amid the hopes that the Bureau will be given additional time for its post-enumeration processing of the data. States are also now looking at what kind of flexibility they’d have to not use the federal census data for state legislative redistricting if its quality is suspect, but several states would have to change either their laws or constitutions to use for redistricting a data source other than the U.S. Census.

What states would use instead is a difficult question.

Embarking on their own state-wide counts poses the same logistical and financial challenges of a federal census.

“I don’t think that many states have the resources to really do the kind of state census that would be acceptable to the courts for redistricting,” O’Hare told TPM.

Another option would be to find an alternative data source — including looking at commercial data cases — that could be proven to to be more accurate as the 2020 federal decennial’s numbers.

“People are giving thought to this, but there’s no solution yet,” Wice, a veteran redistricting lawyer, said.

Can Sampling Fill In the Gaps?

It may be possible to avoid some of these extreme steps if statistical sampling can be used to mitigate the count’s shortcomings, though the Bureau’s ability to do so likely depends on how much time it is given for post-enumeration work that typically happens on the back end.

There are also legal and political hurdles to this approach as well. By law, sampling cannot be used for apportionment. And if Congress were to change that law, there’d be a court battle over the constitutionality of the use of sampling for that purpose.

But the path is a little clearer for using modeling to correct the numbers for other purposes, and federal law already commands the Commerce Secretary to consider using sampling in non-apportionment circumstances.

But there could be political resistance to that route, as it would create a new set of winners and losers.

“If the data are improved, there will be losers. The winners [under the flawed data] would no longer be winners,” said Andrew Reamer, a George Washington professor who is an expert in the funding implications of the census.

And beyond the legal and political questions, the effectiveness of this approach will depend on just how flawed the hard count is in the first place.

“The more screwed up the original count, the farther away from real information you end up, even with adjustment,” Levitt said.