Family spokesman Andy Brack, who also served at times for Hollings as spokesman during his Senate career, said Hollings died early Saturday.

Hollings, whose long and colorful political career included an unsuccessful bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, retired from the Senate in 2005, one of the last of the larger-than-life Democrats who once dominated politics in the South.

He had served 38 years and two months, making him the eighth longest-serving senator in U.S. history.

Nevertheless, Hollings remained the junior senator from South Carolina for most of his term. The senior senator was Strom Thurmond, first elected in 1954. He retired in January 2003 at age 100 as the longest-serving senator in history.

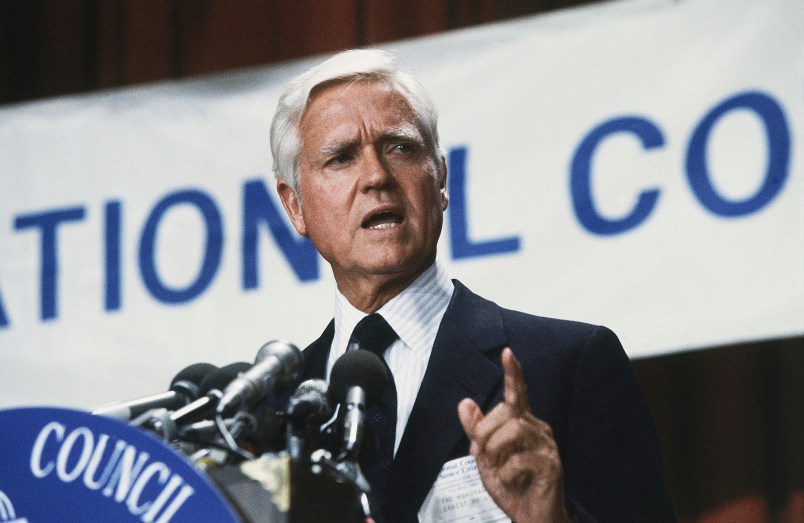

In his final Senate speech in 2004, Hollings lamented that lawmakers came to spend much of their time raising money for the next election, calling money “the main culprit, the cancer on the body politic.”

“We don’t have time for each other, we don’t have time for constituents except for the givers. … We’re in real, real trouble.”

Hollings was a sharp-tongued orator whose rhetorical flourishes in the deep accent of his home state enlivened many a Washington debate, but his influence in Washington never reached the levels he hoped.

He sometimes blamed that failure on his background, rising to power as he did in the South in the 1950s as the region bubbled with anger over segregation.

However, South Carolina largely avoided the racial violence that afflicted some other Deep South states during the turbulent 1960s.

Hollings campaigned against desegregation when running for governor in 1958. He built a national reputation as a moderate when, in his farewell address as governor, he pleaded with the legislature to peacefully accept integration of public schools and the admission of the first black student to Clemson University.

“This General Assembly must make clear South Carolina’s choice, a government of laws rather than a government of men,” he told lawmakers. Shortly afterward, Clemson was peacefully integrated.

In his 2008 autobiography, “Making Government Work,” Hollings wrote that in the 1950s “no issue dominated South Carolina more than race” and that he worked for a balanced approach.

“I was ‘Mister-In-Between. The governor had to appear to be in charge; yet the realities were not on his side,” he wrote. “I returned to my basic precept … the safety of the people is the supreme law. I was determined to keep the peace and avoid bloodshed.”

In the Senate, Hollings gained a reputation as a skilled insider with keen intellectual powers. He chaired the Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee and held seats on the Appropriations and Budget committees.

But his sharp tongue and sharper wit sometimes got him in trouble. He once called Sen. Howard Metzenbaum, D-Ohio, the “senator from the B’nai B’rith” and in 1983 referred to the presidential campaign supporters of former Sen. Alan Cranston, D-California, as “wetbacks.”

Hollings began his quest for the presidency in April 1983 but dropped out the following March after dismal showings in Iowa and New Hampshire.

Early in his Senate career, he built a record as a hawk and lobbied hard for military dollars for South Carolina, one of the poorest states in the union.

Hollings originally supported American involvement in Vietnam, but his views changed over the years as it became clear there would be no American victory.

Hollings, who made three trips to the war zone, said he learned a lesson there.

“It’s a mistake to try to build and destroy a nation at the same time,” he wrote in his autobiography, warning that America is now “repeating the same wrongheaded strategy in Iraq.”

Despite his changed views, Hollings remained a strong supporter of national defense which he saw as the main business of government.

In 1969 he drew national attention when he exposed hunger in his own state by touring several cities, helping lay the groundwork for the Women, Infants and Children, or WIC, feeding program.

A year later, his views drew wider currency with the publication of his first book “The Case Against Hunger.”

In 1982, Hollings proposed an across-the-board federal spending freeze to cut the deficit, a proposal that was a cornerstone of his failed presidential bid.

He helped create the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and write the National Coastal Zone Management Act. Hollings also attached his name to the Gramm-Rudman bill aimed at balancing the federal budget.

Hollings angered many of his constituents in 1991 when he opposed the congressional resolution authorizing President George Bush to use force against Iraq.

In his later years, port security was one of his main concerns.

As he prepared to leave office, he told The Associated Press: “People ask you your legacy or your most embarrassing moment. I never, ever lived that way. … I’m not trying to get remembered.”

He kept busy after the Senate helping the Medical University of South Carolina raise money for the cancer center which bears his name and lecturing at the new Charleston School of Law.

Hollings’ one political defeat came in 1962 when he lost in a primary to Sen. Olin Johnston. After Johnston died, Hollings won a special election in 1966 and went to the Senate at age 44, winning the first of his six full terms two years later.

Ernest Frederick Hollings was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on Jan. 1, 1922. His father was a paper products dealer but the family business went broke during the Depression.

Hollings graduated from The Citadel, the state’s military college in Charleston, in 1942. He immediately entered the Army and was decorated for his service during World War II. Back home, he earned a law degree from the University of South Carolina in 1947.

The next year, he was elected to the state House at age 26. He was elected lieutenant governor six years later and governor in 1958 at age 36.

As governor, he actively lured business, helped balance the budget for the first time since Reconstruction and improved public education.

___

Former Associated Press Writer Bruce Smith contributed to this story.