The story of West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency was an utterly strange one from the beginning.

A coalition of red states and coal companies took legal action not against any current agency regulation, but against the specter of a hypothetical rule limiting greenhouse gas emissions from power plants that the EPA may craft in the future. Weird.

Then the Supreme Court decided to take up the case — even after the Biden administration tried to wave them off, saying essentially that it is working on a new rule and that it’s better to save the inevitable litigation until that regulation is completed. Weirder.

That set up a case with the EPA and power plants on the same side, the EPA asking to regulate the industry and power plants asking to be regulated. Weirdest!

Monday’s oral arguments were a testament to the bizarreness of the red states’ and coal companies’ approach, as almost all of the questions centered on the idiosyncrasies of the case. Larger questions of agency power and congressional delegation, some of the most important ripple effects this case could have, were largely relegated to the back burner.

One of the biggest points of fixation was whether the red state and coal company team has standing to bring the case at all. What injury are they suffering, the government asked, if there is no regulation on the books constraining them?

A lower court — the D.C. Circuit — knocked down the Trump-era Affordable Clean Energy rule (ACE), and the Biden administration has said it has no intention to revive the Clean Power Plan (CPP), ACE’s Obama-era predecessor, because its goals are now obsolete.

“You got the ruling you wanted, vacatur of the ACE Rule,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor said.

“So… how do you have standing?” she asked.

Jacob Roth, attorney for the coal companies, somewhat disingenuously said that there’s still the threat of a CPP come back to life, before getting at what his coalition really wanted.

“We still obviously have a dispute about what the statute means and what the agency is allowed to do,” Roth said, referring to the part of the Clean Air Act which gives the EPA this power to regulate emissions in the first place.

The deregulatory interests in the case, largely fossil fuel companies and the states that house them, are eager for this very conservative court to hack away at the EPA’s power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. They’re making the bid for that now, rather than waiting for the Biden administration to come out with a new rule and fight about it then.

What worries court watchers is that at least four of the justices — the number needed to take up a case — were willing to entertain that notion.

The red state and coal company coalition also invoked the major questions doctrine, which holds that in order for an agency to enforce a regulation that has vast economic and social significance, it must be empowered by Congress to take that precise action. They claim that EPA is wielding enormous power to remake the energy sector, and that it must be curtailed.

The weirdness comes in with the specifics of that argument. They claim that regulation that applies plant by plant (known as “inside the fence”) does not have those major ramifications, but that broader regulation involving trading energy credits and averaging emissions across the grid (“outside the fence”) does.

That position is so strange that it drove power plant companies into the arms of EPA, as the two entities argued side by side. Power plants want the flexibility to transact across the grid; it’s how the industry works. And it’s much cheaper for them to, say, buy clean energy credits from another plant than to equip an outdated coal plant with technology to lower its individual emissions.

“Inside-the-fence reform can be very small or it can be catastrophic,” Justice Elena Kagan pointed out. “There are inside-the-fence technological fixes that could drive the entire coal industry out of business tomorrow.”

While the justices asked about and poked holes in those issues, questions of delegation took a back seat. And almost all of what questions there were centered on the “economic and social effects” piece of the major questions doctrine more than its limits on agency regulation.

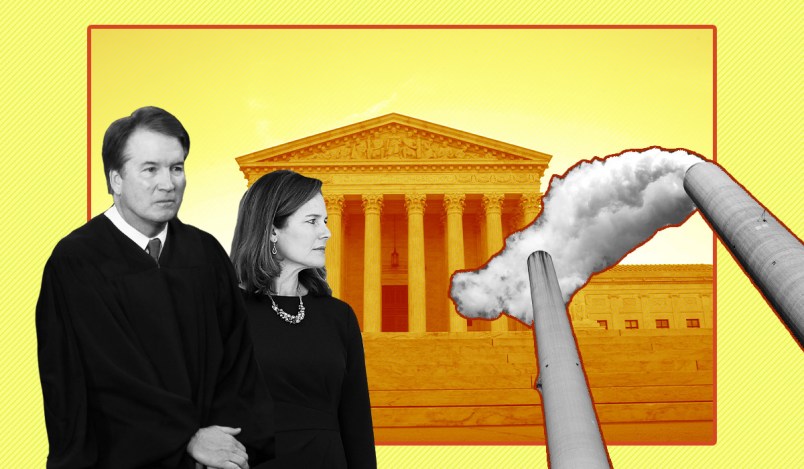

At one point, Barrett said that regulating greenhouse gasses seems pretty strictly within what EPA is supposed to do, when it comes to applying the major questions lens.

She referred to an earlier case about “the FDA staying in its lane” when it came to its inability to regulate tobacco.

“Or if you’re thinking about the eviction moratorium case from earlier this term it was if — what? — the CDC can regulate the landlord-tenant relationship,” she said. “Here if we’re thinking about EPA regulating greenhouse gasses. Well, there’s a match between the regulation and agency wheelhouse.”

The underlying case may not ultimately matter much. At least four justices clearly had an interest in taking it up, knowledgeable of the standing questions and odd legal arguments.

If that interest was to narrow the parameters of what the EPA can regulate based on some tortured reading of the Clean Air Act, the court can still do that. If that interest was to deal a resounding blow to agency power writ large, the court may have the votes to do that too.

In keeping with the strangeness of this case, there could also be another option. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh mused, couldn’t the Biden administration EPA come out with its own rule while the court deliberates, making this whole effort a big waste of time?

“It would depend on what the new rule is,” Lindsay See, solicitor general of West Virginia, responded. “If there is a final rule issued, this case very likely would be moot.”