The Supreme Court issued a major ruling Thursday curtailing the Environmental Protection Agency’s power to regulate power plant emissions, and sent a shot across the bow of executive agency power in general.

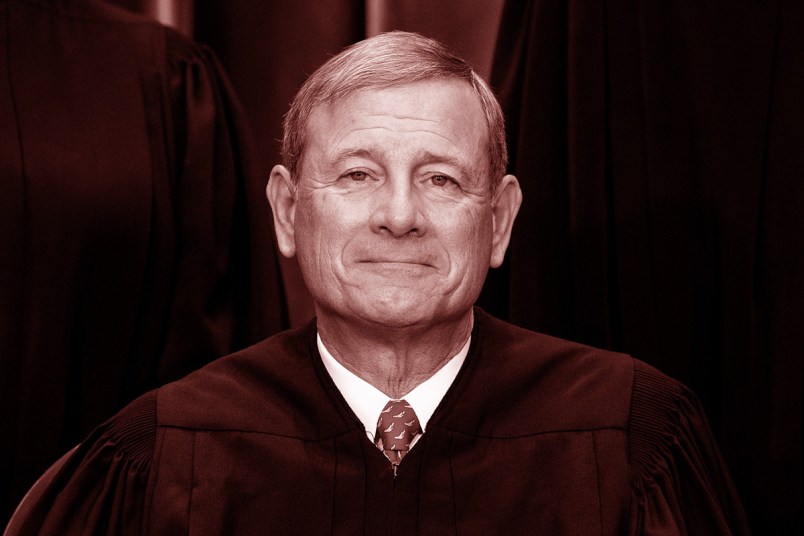

Chief Justice John Roberts delivered the opinion for the Court. Justice Elena Kagan wrote for the dissenting liberals, and Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a concurrence, joined by Justice Samuel Alito.

“Congress did not grant EPA in Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act the authority to devise emissions caps based on the generation shifting approach the Agency took in the Clean Power Plan,” Roberts writes.

While the case makes clear that conservative majority is very hostile to exercises of agency power, it does not go as far as environmentalists feared it might. It insists on plant-by-plant regulations (known as “inside the fence”) rather than ones across the grid (“outside the fence”), but doesn’t completely toss the agency’s ability to regulate climate change-causing emissions.

Roberts claims that this is a “major questions case,” a nod to a theory favored in the rightwing judicial world that demands agencies be exacting when interpreting the powers Congress has delegated to them. Pushing a transition to cleaner, renewable sources of energy, Roberts writes for the majority, goes beyond what Congress intended when it gave the EPA the authority to regulate air pollutants.

He points to Congress’ lack of legislating on the issue as proof, though Republicans have long blocked any significant climate change bills and have only recently, and tepidly, accepted the fact of the crisis’ existence.

The majority opinion is a clear statement of antagonism to exercises of agency power, with Roberts proudly listing recent Court decisions curtailing agency authority.

Leading the dissent, Kagan lists the cataclysmic results of climate change, saying that Congress absolutely gave the EPA the power to address “big” and “new” problems like those threatening the planet.

She also points out the bizarreness in the Court taking this case premised on an Obama-era rule that is not currently in place, and that the Biden administration has no plans to revive.

“But this Court could not wait—even to see what the new rule says—to constrain EPA’s efforts to address climate change,” she writes.

“The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it,” she adds later. “When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear as get out-of-text-free cards.”

In some neat symmetry — his mother had tried to dismantle the EPA as administrator during the Reagan administration — Gorsuch takes a victory lap in his concurrence, singing the praises of the major questions doctrine. He cheers the lack of movement in Congress, saying its slowness is a feature, not a bug.

“Admittedly, lawmaking under our Constitution can be difficult. But that is nothing particular to our time nor any accident,” he writes. “The framers believed that the power to make new laws regulating private conduct was a grave one that could, if not properly checked, pose a serious threat to individual liberty.”

He spends less time considering that Congress’ glacial pace will leave a planet devastated by climate change and, eventually, inhabitable for humans.

This case had had court-watchers on high alert since the Court took it up in the fall. It was a bizarre choice — red states and coal companies rest much of their argument on the Obama-era Clean Power Plan, which is not on the books and which the Biden administration has no intent to revive.

The coalition wanted the Court to rule that the Clean Power Plan would have been outside the EPA’s authority to enforce under the Clean Air Act, putting guardrails on the agency’s power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

Court watchers feared that the case could be a win-win for the red states, given the amenability of the conservative justices. Either the conservative Court could make a narrow reading based on the statutory text, and handcuff the EPA from regulating one of the country’s biggest polluters. Or it could go further, and make a sweeping statement about the limits of agency power, which could reverberate throughout the entire administration.

In the end, Roberts walked a path between the two scenarios, curtailing the EPA’s power without explicitly extending his ruling to other agencies. He still, however, waved toward further Supreme Court rulings restricting executive authority with his invocation of the major questions doctrine.

The justices’ intent was obfuscated at oral arguments by the many idiosyncrasies of the case. They spent less time on the big questions of agency power, and much more puzzling over the case’s pedestrian questions — like whether the petitioners had standing to even bring this lawsuit in the first place.

Still, that gave Democratic lawmakers who filed a brief in the case little hope. “It seems they’re clearly determined to strike down a lot of good regulation,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) told TPM at the time.

Read the opinion here: