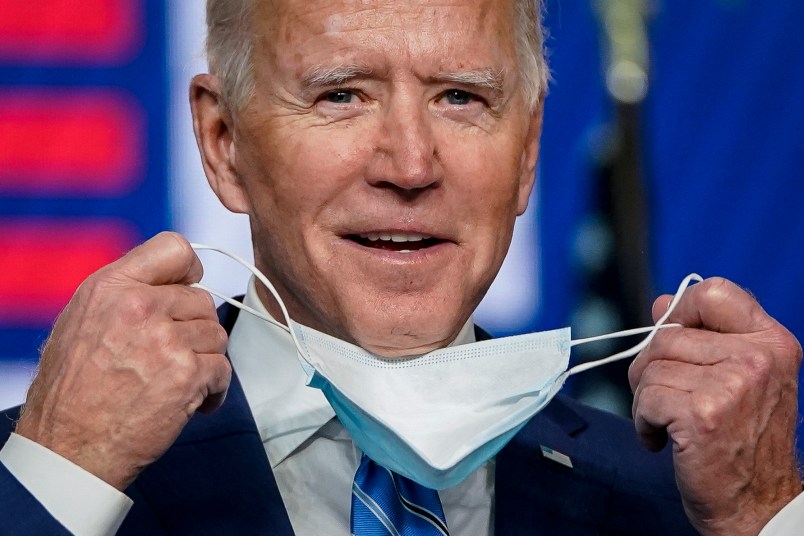

In one respect, President-elect Joe Biden faces a grim Jan. 20: an additional hundred thousand could be dead of COVID-19 between now and then, with case rates and hospitalizations skyrocketing around the country as the President copes with his loss by playing golf.

And to address the problem, the President-elect faces a bleak political landscape. Absent a double Democratic victory in Georgia Senate runoffs in January, Biden could face a serious roadblock — in the form of Mitch McConnell — constraining parts of his COVID-19 agenda.

Biden’s COVID-19 response plan focuses on seven areas, which would address portions of the Trump administration’s response to the virus that have been alternately disastrous or uncoordinated.

Portions of the Biden plan offer new approaches to combatting the virus that the Trump administration eschewed, including extensive use of the Defense Production Act to alleviate PPE shortages and huge investments in contact tracing and local public health services.

But other portions of it, like calls to heed scientific advice and leave career professionals at the FDA and CDC unhindered, may warm the hearts of the scientific and medical communities but leave others somewhat skeptical and worried about the limits of what the President-elect can accomplish.

“All that’s essential, but it’s not sufficient,” said Gary Slutkin, a former WHO epidemiologist. He said that without support from constituencies that remain skeptical of measures to slow the virus’s spread, including conservative Republicans, the disease would likely to continue to progress through the United States.

The plan, available on the campaign’s transition website, showcases a few narrow areas where Senate Republicans have signaled interest in engaging.

Vaccines

In particular, the Senate GOP passed a provision in its “skinny” COVID-19 relief bill in September for vaccine distribution, offering $29 billion for the development and distribution of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics.

Biden’s plan calls for $25 billion for vaccine development and distribution alone. That number is in line with Centers for Disease control and state officials who say that they need billions to get a COVID-19 vaccine distributed to the entire population.

State officials in particular have said that distributing a COVID-19 vaccine without billions in additional funding would be impossible, applying their lobbying focus to Congress.

Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has said that he supports a second relief bill and money for vaccine distribution, though at a much smaller scale than the Democratic proposals. McConnell has also said that he opposes a bill larger than the $500 billion that he’s offered, citing bogus concerns involving austerity. The money needs to be appropriated by Congress, so, absent a Democratic majority, buy-in from the GOP will be necessary.

It’s not clear how that will be resolved.

PPE And Testing

On other fronts, Biden has broad tools available to him made possible by the office of the presidency.

For getting PPE out to doctors and health-care workers, for example, Biden has said that he would make extensive use of the Defense Production Act — a law that allows the executive branch to compel the production of needed items. The Trump administration declined to use it in a serious way, save for seizing shipments of masks and sanitary gowns that were already en route.

Biden’s testing plan would revamp the Trump administration’s approach to the topic, which lacked any coherent national framework and left it to states and local jurisdictions to fend for themselves as the President repeatedly complained that increased testing was making him look bad.

Part of Biden’s approach would also involve investing in technology that would enable accurate at-home testing, and would ramp up the production of COVID-19 tests through the creation of a Pandemic Testing Board to coordinate supply chains for that effort.

The Biden administration will also aim to create a 100,000 person-strong Public Health Jobs Corp that would undertake contact tracing.

That provision would require additional funding and may also require a statute creating the corps, likely to be nestled within the Department of Health and Human Services. That could end up needing congressional support to be implemented.

Public Health Guidance

Arguably the most difficult-to-implement portion of the plan focuses on public health guidance.

Slutkin, the former WHO epidemiologist, said that the difficulty would be doing a public health education campaign to address the virus that involves “peer outreach to all sectors of society.”

This has less to do with Congress and more to do with anti-mask ideas that President Trump and others on the right have spent the past eight months spreading.

Slices of society that have been primed to be resistant to measures like mask mandates will have to be convinced. Biden said in the plan that he will try to address this through outreach to governors and mayors responsible for issuing state and local mask mandates, as opposing to issuing a federal mask mandate that would blanket the country.

Other elements of the plan involve revamping guidance for when to reopen and when to increase social distancing in the face of surging case counts.

There are elements of this that will require congressional support, however.

The plan involves new appropriations that would provide relief funding supporting state and governments and small businesses through lockdowns, as part of a “renewable fund” for government and a “restart package” for COVID-afflicted small business.

Those proposals remain vague, but with governments saying that they need hundreds of billions of dollars to weather the ongoing storm, Congress would need to appropriate money that goes beyond the $500 billion on tap in the McConnell plan.