When Trump administration’s senior HHS staff unveiled a draft rule this week that would expand the sale of cheap, skimpy, short-term health plans, they described it as a “lifeline” for the currently uninsured, and insisted the rule change won’t destabilize Obamacare’s individual market.

The department’s move is just the latest in a lengthy series of administrative actions that have destabilized and chipped away at the Affordable Care Act, including repealing of the individual mandate, cutting the length of open enrollment in half and slashing funding for outreach and assistance, making it easier for states to cull their Medicaid enrollees, and cutting off CSR subsidies that offset the cost of insuring low-income individuals.

While Obamacare’s individual mandate was still in place, those who chose a cheap, short-term, non-ACA plan still had to pay the tax penalty. With that barrier removed next year, the introduction of the skimpy plans could upend the health care marketplace.

On a call with reporters on Tuesday, HHS insisted the new rule would only cause up to 200,000 people to leave their comprehensive Obamacare plan for a cheaper, deregulated, short-term plan, and that the drain of those people would not have a major impact on those who remain in Obamacare-compliant plans. CMS Administrator Seema Verma said repeatedly that the rule is aimed squarely at the 28 million people in the country who remain uninsured, the “healthy people sitting on the sidelines without coverage.”

But health care experts and economists say the plans—which can charge people higher premiums if they have a pre-existing condition, reject them altogether, and refuse to cover basics like emergency room visits and prescriptions drugs—are mainly aimed at enticing people out of Obamacare’s individual market.

“Rather than eliminate the ACA’s consumer protections, this is simply creating a parallel insurance market that lacks those protections,” Larry Levitt with the Kaiser Family Foundation told TPM. “This is a back door way of creating largely unregulated insurance plans that will siphon off healthy people.”

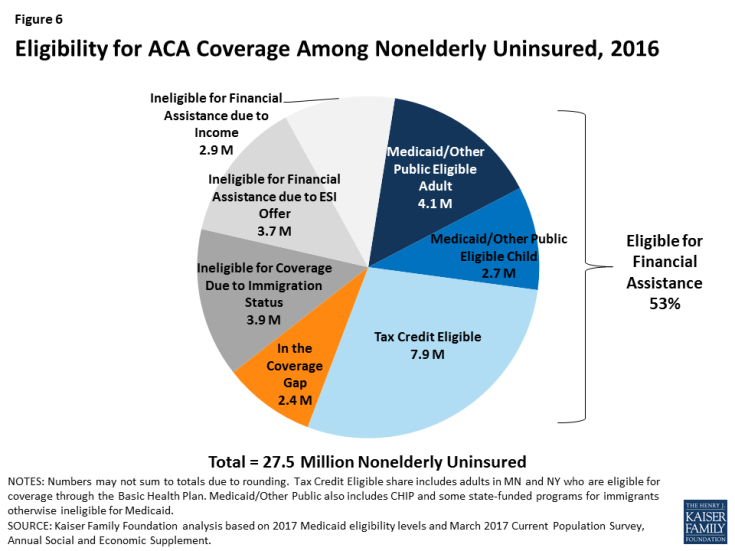

Levitt says the plans may not be appealing to much of the currently uninsured population, more than half of whom could qualify for free or heavily subsidized plans in the ACA market. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 53 percent of uninsured people would qualify for significant financial assistance through either Medicaid or the individual market’s federal tax credits, and those free or nearly-free plans would offer them comprehensive coverage regardless of their health status.

While that leaves several million uninsured people who may be interested in a short-term insurance plan, Levitt says insurers are much more likely to target people in Obamacare’s individual market whose incomes are too high to qualify for subsidies and who are healthy enough to consider a skimpier plan.

“You can bet that insurance companies will aggressively market these plans to healthy, middle class people who find themselves priced out of the ACA-compliant market,” he said. “But the administration is right in a sense: people who will become uninsured once the individual mandate is repealed, because premiums will go way up for the unsubsidized, may be interested in these short-term plans.”

Because the short-term plans are allowed to charge people much higher premiums or exclude them based on their age, gender, and health status, only younger and healthier are expected to leave the individual market to use this new option.

“Without question the end result will be a smaller and sicker individual market, with higher prices and fewer plan choices for those who remain,” Sabrina Corlette, a professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute, told TPM.

Unsubsidized patients who have too many health problems to consider a skimpy short-term plan may be the most harmed by the rising premiums that will result. And by HHS’ own estimate, taxpayers will take a hit as well, as the ACA’s tax credits will have to increase for millions of people in the individual market as premiums rise.

Back in December, when the Trump administration announced it would explore allowing unregulated short-term insurance plans up to one year in length, a group of health care industry and patient advocate groups wrote a letter to HHS warning that the policy would “lead to higher premiums for consumers, particularly those with pre-existing conditions. Further, these actions destabilize the health insurance markets that guarantee access to comprehensive health coverage regardless of health status.”

The signees, including the American Cancer Society, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), said they hoped states would step up to strictly regulate short-term health plans if the federal rule is finalized, and require insurance companies to offer “clear and accurate disclosures to consumers” so they aren’t caught with massive medical bills unawares.

Corlette says that lack of disclosure is a major concern.

“In just the last few months, state insurance departments have been putting out fraud alerts because of the marketing of these products can be pretty deceptive,” she said, citing Indiana, Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa and Pennsylvania as just a few examples. “A lot of people buy them thinking they’re comprehensive insurance and will provide financial protection to them, only to find out to their dismay that they don’t cover very much at all. And because short-term policies are not required to disclose all of their exceptions and limits and caps, in some cases you don’t even know what you’re buying until after you pay your premiums.”