On Friday, Kentucky became the first state in the nation, and in the nation’s history, to win permission from the federal government to impose a work requirement and several other new restrictions on its Medicaid program.

“It will be transformational in all the right ways,” Governor Matt Bevin (R) said in a speech announcing the waiver approval. “It has been long overdue.”

Friday’s announcement, which by the state’s own estimate will result in more than 90,000 people losing Medicaid coverage, is yet another marker in a massive about-face for health care in the state. Kentucky—which just a few years ago made headlines as an Obamacare “success story,” launching its own health insurance exchange and expanding Medicaid to more than 400,000 low-income residents—has seen a sharp reversal since electing a Tea Party governor in 2015.

With a whopping one-third of the state’s population now enrolled in Medicaid, and with state resources strained by a full-blown opioid addiction crisis, the fate of the new Medicaid work requirements will determine the future of health care not just for Kentucky but the nine states and counting who have their own waiver applications pending before Trump’s Department of Health and Human Services.

“Kentucky will soon be the unfortunate poster child of this dangerous policy,” lamented Rep. John Yarmuth (D-KY). “My only hope is that the chaos caused by this policy and the desperation of the Kentucky families who will soon lose their only access to health coverage will force Governor Bevin to demonstrate some level of compassion and reverse this disgraceful policy.”

A southern success

When Obamacare’s insurance exchanges launched in 2013, most southern states fought the new system at every turn, refusing to either expand Medicaid or create their own state health insurance exchanges, and taking the Obama administration to court.

Kentucky took a different path, setting up the Kentucky Health Benefit Exchange, dubbed “Kynect” for short, which ended up enrolling more than half a million people. In 2014, under Democratic Gov. Steve Beshear, the state became the first in the southeast to expand Medicaid, and remains the only one in that region today.

By 2015, the state’s uninsured rate had dropped from 20.4 percent to just 9 percent, the second largest percentage drop of any state in the country. By the end of 2016, the state was tied with West Virginia for the biggest percentage increase in health coverage.

Emergency room visits dropped and fewer people reported skipping medication because of its cost. A state study in 2015 found that expanding Medicaid had created 12,000 jobs. By the end of 2015, nearly two-thirds of the population reported a favorable view of the Medicaid expansion, and more than 70 percent said they would rather “keep the state’s Medicaid program as it is today rather than change it to cover fewer people.”

Elections have consequences

Everything changed in 2015.

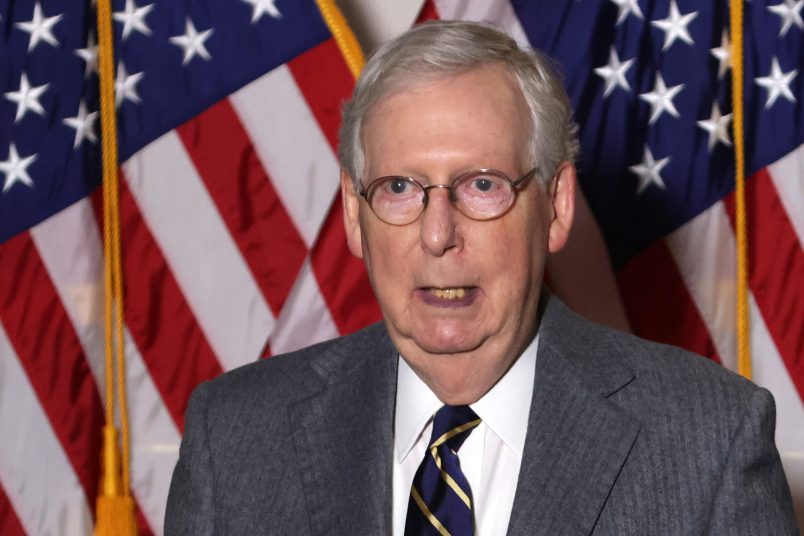

Bevin, who failed to unseat Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell in 2014, triumphed in a gubernatorial election marked by abysmally low turnout.

All counties have reported unofficial vote totals, which are available at https://t.co/o3wpyCUmkm. Based on that info, turnout was ~30.7%.

— Alison L. Grimes (@KySecofState) November 4, 2015

Bevin ran on an anti-Obamacare platform and, like President Trump, immediately set about reversing his Democratic predecessor’s health care agenda when he took office.

Bevin shut down the state’s popular Kynect exchange, moving the individual market back onto the federal Healthcare.gov platform, and after threatening to completely undo the Medicaid expansion, opted to restrict eligibility instead.

The state aims to save more than $300 million by cutting nearly 100,000 people from its Medicaid rolls. Its federal waiver request was drafted in 2016 with help from Seema Verma, who went on to become the Trump administration’s CMS administrator—the official responsible for approving that very request.

Bevin has also supported efforts at the national level to scrap pieces of Obamacare, including the rule that all insurance plans cover 10 essential health benefits. He derided that provision at a town hall in 2017, saying: “I don’t need maternity benefits because I don’t expect I’ll be expecting.”

Health care whiplash

Kentucky has now won permission to make Medicaid only available to non-disabled adult residents who work at least 20 hours per week, volunteer, study, or take care of a family member. Former foster care youth, pregnant women, and full-time students are exempt from the work requirement.

The state also got the ability to charge low-income Medicaid recipients health care premiums, eliminate full coverage of dental care, vision services, and over the counter medications for many adults, end retroactive Medicaid coverage, and implement a six-month lockout period for people who fail to re-enroll in time or report a change in income.

Leonardo Cuello, the director of health policy at the National Health Law Program, believes many of these provisions are subject to court challenges because they violate Congress’ original intent for Medicaid and do not meet the waiver law’s requirement that they consist of a novel policy experiment.

“There are, for example, countless studies showing that charging premiums to people with very low incomes will result in them not being able to pay and losing coverage,” he told TPM. “So that’s not an experiment. We already know what will happen. It’s like saying, ‘I want to experiment by running at full speed into a brick wall and seeing what will happen.'”

Particularly harmful for Kentucky, Cuello said, is the provision ending the three-month retroactive coverage to which Medicaid recipients are usually entitled.

“Normally, if I’m uninsured, and had a heart attack in March and then applied for Medicaid in April, all of my hospital bills would still be covered,” he explained. “Seeing as medical bills are one of the biggest causes of bankruptcy in the country, this is important for not just the individual but the hospital and the entire health care system. So it’s particularly problematic in states like Kentucky where rural hospitals are already financially strapped. Telling them they won’t get reimbursed for a lot of really expensive care they provide is a terrible policy.”