When the House finally managed to pass a bill to care for the first responders and other survivors suffering from 9/11-related illnesses in late 2010, few thought it stood much of a chance of becoming law.

Senate Republicans promised a filibuster. Democrats, just weeks away from losing the House, were running out of time to pass top priorities. The impending lame-duck session of Congress was already so packed with other top issues — repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, the DREAM Act, extending the Bush tax cuts — that it appeared almost impossible to get another big-ticket item on the schedule.

A failure then might been the final blow to the bill that would eventually become the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act. Zadroga was a NYPD detective who’d died from his exposure to Ground Zero chemicals. The eponymous bill promised health care and financial relief to tens of thousands of first responders, volunteers and others suffering from 9/11-caused cancers and other health problems.

Lawmakers had taken years to get it through the Democratic-controlled House. Then-Sen. Majority Whip Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Hillary Clinton, the bill’s original Senate champion, had so far failed to pass the bill through the upper chamber.

Faced with that grim picture, Schumer handed the reins to Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), a Senate rookie who’d been appointed to Clinton’s seat the year before. Few advocates expected it to pass, and were shocked when she helped push it across the finish line.

“She was absolutely instrumental. Without her, this would never have passed the Senate. It wouldn’t have gotten done,” said 9/11 Health Watch President Ben Chevat, who as Rep. Carolyn Maloney’s (D-NY) chief of staff during the bill’s long slog through Congress played a huge role in the law’s passage.

Gillibrand’s role in the law’s passage is a key, and often overlooked, part of her political resume — one that primary voters will likely hear more about in the coming months.

She’s already touted the bill numerous times on the campaign trail, bringing it up twice during her campaign announcement on Stephen Colbert’s show and returning to it multiple times during her first visit to New Hampshire last weekend.

“I have shown through my 12 years of public service that I can reach across the aisle and work with literally anybody,” she said in Manchester, New Hampshire on Saturday. “The men and women who raced up the towers when everyone was coming down and then did the horrible work of finding survivors and then remains after the towers fell, they started to die of horrible cancers because of the toxins they breathed in. I worked with the women senators, the Republican women senators to find common ground. We ultimately passed that bill unanimously, twice.”

Gillibrand faces plenty of hurdles to making a serious play for the Democratic nomination. She barely registers in current polls, and her past positions on gun control and immigration as well as early corporate legal work are politically problematic. But those who worked with her closely on this issue warn not to underestimate her.

“It was sheer force of her personality that got that through,” former Sen. Mark Kirk (R-IL), who was the top GOP sponsor of the law’s reauthorization in 2015, told TPM. “She should be taken seriously [as a candidate]. I found her on the Zadroga Act to be utterly relentless and good to work with, very well-grounded in what’s the right thing to do.”

John Feal was a construction foreman working to clear the Ground Zero pile in the days after the attacks when a steel beam fell on him. He almost died and lost half a foot. He soon emerged as a top advocate for the bill, organizing groups of first responders to shame lawmakers into supporting them. He’s lobbied Congress roughly 80 times.

The plainspoken Army veteran dislikes most politicians — he famously called then-House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-VA) an “asshole” during a press conference for stalling the bill. He was deeply skeptical of Gillibrand when he first met her.

“I thought she was just fly by night. … and then I saw her starting to work. She’s a master, ” Feal told TPM. “I’ve met everyone, and there’s probably like five people I actually like and trust on both sides of the aisle, and you can feel the goodness in her. … She’s got bigger Abe Lincolns than 99 percent of the men in D.C.”

High Stakes, Low Hopes

In late 2010, Republicans weren’t eager to give Democrats an expensive new program whose beneficiaries were disproportionately from the blue-hued New York City tristate area.

Tea party conservatives, at the height of their anti-spending fever, said the program would prove too expensive and an easy target for fraud. Sen. Tom Coburn (R-OK), a deficit hawk who more than earned his “Dr. No” nickname, and Sen. Mike Enzi (R-WY), then the top Republican on the influential Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, led the charge in opposing the bill. The version of the bill that passed the House had pay-fors that Republicans would never accept. Democrats from President Obama on down supported the bill, but most weren’t pushing to prioritize it in the lame-duck session.

Gillibrand was undaunted.

She buttonholed GOP lawmakers, guilting them for turning their backs on the victims of 9/11, sounding them out on ways to tweak the bill and agreeing to shrink the programs’ funding from 20 to 10 years to win over Republicans. With Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Susan Collins (R-ME), she helped gradually build bipartisan support until the bill had more cosponsors than the 60 needed to overcome a filibuster. She helped the first responders who’d spent years lobbying for the bill find the right pressure points in Congress to work over.

At one point, she met privately with then-Fox News head Roger Ailes, pushing him to rally support for the bill. Ailes was supportive during the meeting, according to two sources familiar with the conversation. Fox was slow to act, but after Jon Stewart dedicated an entire episode of the Daily Show to shaming lawmakers on the bill, the conservative news network joined in with a regular drumbeat of segments hammering Republicans for blocking it.

“Privately, people were very concerned that time was going to run out before the end of the Congress,” Brian Fallon, a top Schumer adviser at the time, told TPM. “Gillibrand, to her credit, never let those odds stop her from throwing herself into it fully, and I think changed the odds [of success] just through her sheer doggedness.”

Republicans filibustered the bill in early December because they were blocking every piece of Democratic legislation until the Bush tax cuts got a reauthorization vote, nearly dooming it for good.

Schumer convinced then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) to give advocates one more shot, but there wasn’t time left on the Senate calendar, meaning passage would have to be by a unanimous vote. Coburn remained a huge holdout. If the bill didn’t get through by the end of the year, when Republicans took over the House, it was likely done for.

Gillibrand and Schumer kept pushing. They and Enzi held all-night negotiations to address his and Coburn’s concerns that the program could be defrauded and to rein in costs, agreeing trim the program’s length once again — from 10 years to five. (Coburn didn’t respond to a request to discuss this story; Enzi told TPM he didn’t recall the negotiations.) The two sides finally reached an agreement around noon on Dec. 22, just hours away from the session’s end. The Senate rushed through the vote on a voice vote. House leaders had to call back members already fleeing for the holidays, and barely got enough back.

“It was the last vote of the Congress in 2010, literally. We were afraid there weren’t going to be enough people here to get the quorum,” Rep. Peter King (R-NY), a key supporter of the legislation, told TPM.

The bill passed, the final vote of the Democratic House. Almost a decade after the 9/11 attacks, the program finally became law.

Deja Vu

The program has been a huge relief for those suffering from 9/11-related illnesses. More than 84,000 people participate in the health program. The Victims Compensation Fund has paid out almost $5 billion to more than 20,000 victims and their families. That includes for many police officers, more of whom have died from 9/11-related illnesses than died on the day of the actual attacks.

But in spite of the program’s strong track record, the 2015 reauthorization fight was nearly as arduous as the law’s original passage. Republican leaders voiced support for it but argued that it would be tough to find money to pay for it. With both chambers of Congress in GOP hands, the bipartisan group who backed the law had an even tougher time getting the time of day from Republican leaders.

“A lot of our guys quietly didn’t want this to happen,” Kirk, the bill’s top Senate GOP sponsor that year, told TPM.

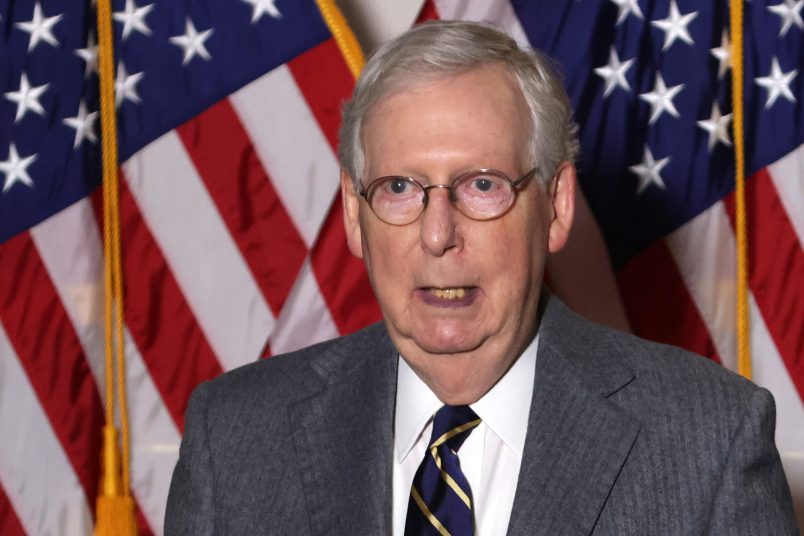

Schumer was the one to force Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) to include it in a broader must-pass bill, but the law’s top advocates say Gillibrand was just as dogged in building bipartisan Senate support for its reauthorization.

Gillibrand played a key role in the bill’s final passage — but doesn’t deserve all the credit.

Maloney, Chevat, and Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-NY) spent years writing the original legislation and getting it through the House. King carried the GOP torch during the final stages of the bill’s original passage and was crucial in getting the law reauthorized in the GOP-controlled Congress in 2015.

Clinton carried the bill in the Senate for years. Schumer stepped in at key moments. The New York Daily News brought the bill national attention with near-daily cover stories. Stewart amplified that message in a huge way. (It was fitting that Gillibrand announced her presidential campaign on Stephen Colbert’s show earlier this month given how close Colbert is to Stewart.)

The 9/11 survivors who relentlessly lobbied Congress were a key reason for the bill’s success — it’s a lot harder for a lawmaker to say no to an abstract program than look an EMT dying from cancer in the eye and tell them you’re not going to help his family.

“I have always said that democracy only works when people stand up and demand it. There is no better example than the 9/11 health bill,” Gillibrand said in a statement to TPM. “It’s heartbreaking that sick and dying heroes had to fight tooth and nail for basic decency and it was an honor to fight by their side.”

But everyone involved says Gillibrand deserves credit for getting the bill through the Senate when no one thought it could pass.

Nadler said Gillibrand was “instrumental” in its final Senate passage, while King, who’s a close Trump ally, credited Gillibrand for “doing all the grunt work through the fall” on the bill’s original passage.

The program has one more big fight coming up. The law’s 2015 reauthorization funded the health program for 75 years but only extended for five years the Victims Compensation Fund, the program that gives money to help make up for lost wages and health costs for victims and their families. Its funding is almost gone.

Gillibrand and her bipartisan allies on the legislation will begin their public push with a Capitol Hill rally with Stewart and surviving advocates in late February.

Feal will be there, ready for one more round with one of the few lawmakers he can stand.

“She’s always an underdog. People always underestimate her. I don’t know if that’s because she’s a woman or in public because she comes off dainty and delicate,” Feal said. “She is a warrior. She is an MMA fighter.”