Conservative justices on the Supreme Court and Republican lawyers love redistricting reform as an argument against the court reining in extreme partisan gerrymandering.

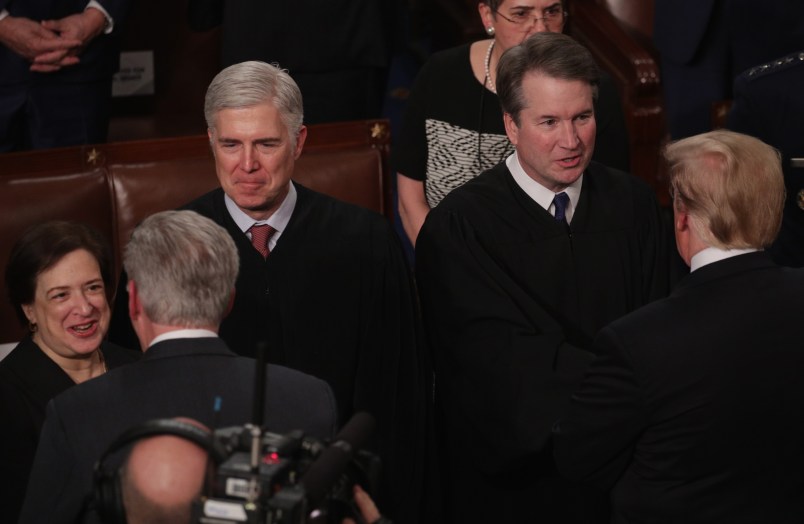

Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh on Tuesday both brought up the push in several states to create independent redistricting commissions and other measures to limit legislators from drawing extremely unfair maps.

Paul Clement — a former U.S. solicitor general in the George W. Bush administration representing North Carolina’s GOP legislature — also pointed to the movement as a reason for the justices not to wade into the question that they have avoided so long.

The justices were hearing on Tuesday two cases: the North Carolina case, Rucho v. Common Cause, challenging a GOP-drawn map, and a Maryland case, Lamone v Benisek , challenging a map drawn by Democrats. The cases asked the justices to consider whether the court should impose limits on extreme gerrymandering. In both cases, lawmakers said the aim of the maps were to draw districts that maximized the electoral advantage of the party in charge.

The court has previously punted on partisan gerrymandering cases on narrower, procedural grounds. Tuesday’s arguments focused almost entirely on the underlying substantive issues.

Gorsuch was the first to bring up the movement towards redistricting reform — citing the constitutional amendment initiative passed in his home state of Colorado last year — to ask Clement about the challengers’ argument that “the Court must act because nobody else can as a practical matter.”

“To what extent have states, through their initiatives, citizen initiatives, or at the ballot box in elections through their legislatures, amended their constitutions or otherwise provided for remedies in this area?” Gorsuch asked, adding “I’m just wondering, what’s the scope of the problem here? ”

Clement took the bait, bringing up both the states that have passed ballot initiatives as well as the potential that Congress could pass reform measures reining in gerrymandering reform.

He mentioned explicitly HR1, the democracy overhaul bill recently passed by the Democratic House, that would require states to set up independent redistricting commissions.

Clement alluded to “constitutional” issues some may have about the legislation, but argued that “it certainly shows that Congress is able to take action in this particular area.”

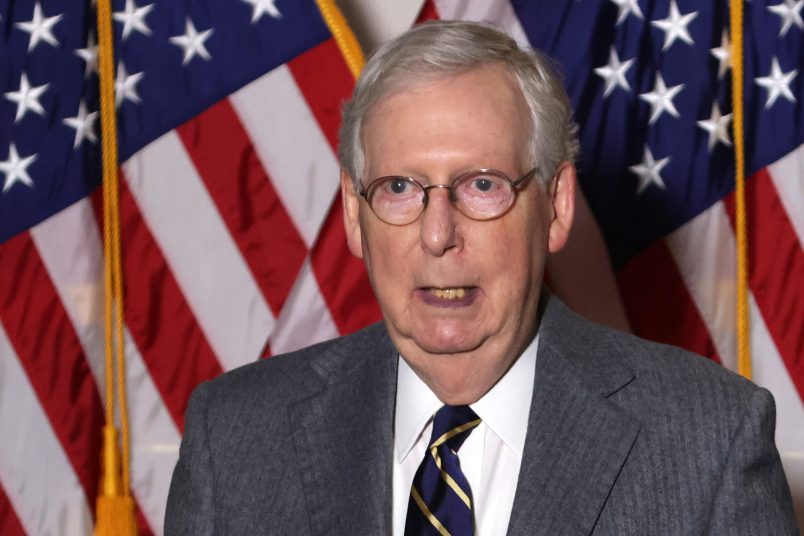

It went unmentioned that HR1 has no chance of passing the GOP-controlled Senate.

Chief Justice John Roberts expressed skepticism. “I suppose the members of Congress are pretty happy with the way the districting has been done.”

Clement responded that the bill was passed on a party-line vote by the majority party in the House, to suggest that Congress can be trusted to institute reforms on a system that benefits it.

Clement’s argument ignores a recent AP analysis that found that House Democrats’ wave in the 2018 midterms would have been 16 seats greater had the political advantage not been baked into the map for the Republicans.

The lawyers arguing for the challengers in the North Carolina case — Emmet Bondurant and Allison Riggs — both brought up that, on a state-level reform front, North Carolina does not allow citizen-initiated ballot measures.

Riggs had to repeat the point, already made by Bondurant, when Kavanaugh again brought up the argument during her line of questioning.

She pointed out that, not just North Carolina, but many states, particularly east of the Mississippi River, don’t offer voters that direct avenue of reform.

Gorsuch interjected again to bring up Congress’ ability to get involved.

“Other options don’t relieve this Court of its duty to vindicate constitutional rights,” Riggs pushed.

There are multiple layers of irony in this being the argument being used against the court reining in partisan gerrymandering.

While Gorsuch and Kavanaugh were not justices at the time, their three current conservative colleagues dissented from an Arizona case okaying the state’s independent redistricting commission, which was being challenged by a GOP legislature. Republican lawmakers have continued to fight — both politically and in lawsuits — voters’ attempts to implement redistricting commissions through ballot initiatives. It’s unclear where the Supreme Court, which has shifted right in recent years, will fall on those cases in the future.

Another irony was that minutes after pointing favorably to the push for independent commissions, Clement seemed to argue against the idea. He was pushing back on a hypothetical test for partisan gerrymandering laid out by Justice Stephen Breyer that would advantage states that used a commission.

“You’re basically saying that it would be a good thing for the state if they chose to use a mechanism other than the one that the framers picked,” Clement said, referencing the Constitution’s delegation of redistricting to state legislatures.

Justice Elena Kagan used this to call him — and Gorsuch — out for their previous line of argument.

“I mean, going down that road would suggest that Justice Gorsuch’s attempt to sort of say, ‘This is not so bad because the people can fix it,’ is not so true because you’re suggesting that the people really maybe can’t fix it, ” she said.

Besides Kavanaugh’s and Gorsuch’s cynical lines of questioning, there are other reasons to think that the Supreme Court wasn’t inclined to vote in favor of the challengers. They showed skepticism toward the hypothetical tests laid out by the challengers’ lawyers — and by the liberal justices themselves. The arguments notable did not delve much into the narrower technical or procedural elements of the cases. This suggests that the Supreme Court, instead of punting on the question for procedural reasons, might be ready to say once and for all what courts’ role should be in regulating partisan gerrymanders. There was almost no indication that a conservative justice was thinking that there should a judicial role at all.