A major legislative package of democracy reforms House Democrats will introduce on Friday is both a notable marker of the emphasis the new majority wants to put on voting rights and the beginning of the process by which Democrats hope to restore the Voting Rights Act, which the Supreme Court gutted in 2013.

According to a summary of the package sent to reporters, the bill — known as “We the People Democracy Reform Act” or HR1 — makes a congressional finding that the 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder led to a wave of voter suppression and instructs Congress to build a record upon the finding.

The House is expected to consider a separate bill that would restore the provision of the Voting Rights Act that the Supreme Court dismantled. That provision required states and localities with a history of racial voter discrimination to get election policy changes pre-approved by the federal government. The bill to address head on the Shelby County decision is moving on its own track, a House Democratic aide told TPM, so the House can build a record of the voter suppression that has happened since the decision came down. Such a public record, legal experts believe, will help protect a VRA fix, if passed, from court challenges conservatives may try to bring against it.

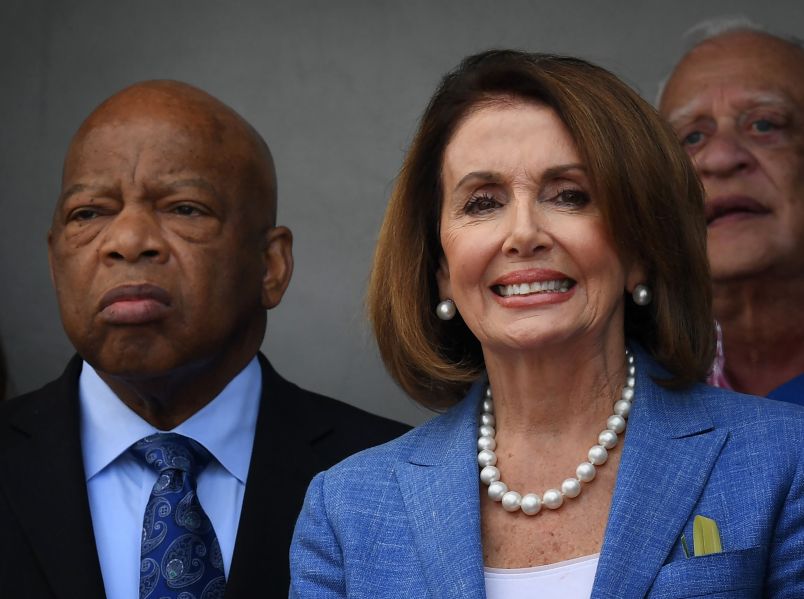

The “We the People” legislation Democratic leaders will be touting at a press conference Friday morning will not include that VRA fix. However, it includes several other provisions expanding the franchise that have been championed by voting rights activists, such as automatic voter registration, same day voter registration, mandated early voting, a requirement that states set up independent redistricting commissions to prevent gerrymander, and a campaign finance overhaul.

A 2017 bill that would fix the Voting Rights Act, called the Voting Rights Restoration Act, gives a sense of what Democrats are thinking about for the bill that would address Shelby directly. That bill proposed a new set of criteria for what would trigger the requirement — known as “preclearance” — that states and localities get approve either from the Justice Department or a federal court to change their election policies.

Since the Shelby decision, there have been a deluge of voting restrictions — including tougher voter ID laws, cutbacks to early voting, and the closure of voting locations — implemented in places that were previously required to get preclearance for election changes.

President Obama’s Justice Department, along with private civil rights organizations, had some success in getting courts to block those requirements. For instance, a North Carolina voter restriction package the GOP legislature passed weeks after the Shelby decision was struck down in 2016 by an appeals court, which said the law targeted minority voters with “almost surgical precision.” A voter ID law that Texas implemented after Shelby, that had previously been rejected twice in preclearance, was invalidated by the extremely conservative 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

But these kinds of legal challenges are costly, and often let states implement the restrictions for years before courts ultimately knock them down. This whack-a-mole approach to enforcing the VRA highlights the need for a new preclearance provision to replace the formula the Supreme Court invalidated, voting rights proponents argue. Even some GOP lawmakers have said they’d support a post-Shelby fix to the Voting Rights Act; however, House Republican leaders refused to let such legislation move forward.

Now that Democrats have control of the speaker’s gavel, they can move forward on laying the groundwork for passing such legislation in the House, while the bill being introduced Friday represents a broader voting rights agenda that tackles numerous elections reforms not specific to addressing the Shelby decision.

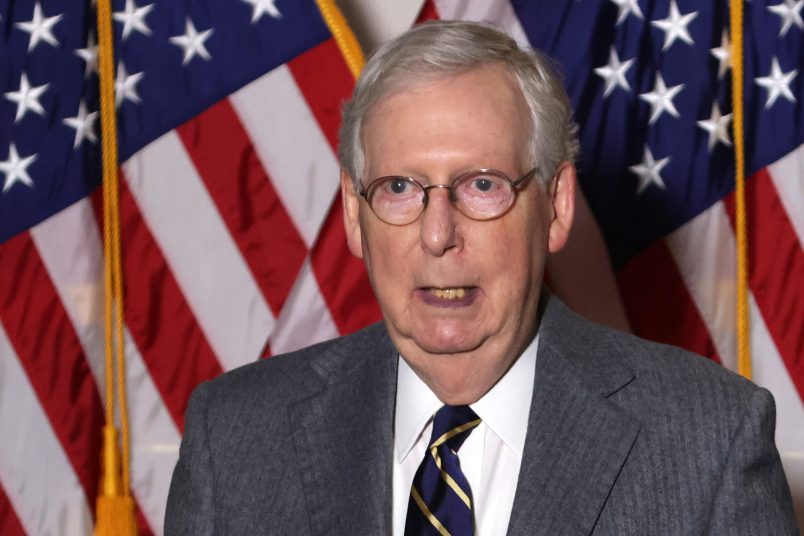

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has already said he has no intention of bringing Friday’s House bill, which also includes an ethics overhaul, up in the Senate. It is unclear if a standalone VRA fix would also be dead on arrival in the Senate.

However, Senate approval is not required for House Dems to begin holding hearings and taking other steps to create the public record they’ll want in place when they try to restore the Voting Rights Act post-Shelby.