WASHINGTON (AP) — As the ravages of the novel coronavirus forced millions of people out of work, shuttered businesses and shrank the value of retirement accounts, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged to a three-year low.

But for Sen. David Perdue, a Georgia Republican, the crisis last March signaled something else: a stock buying opportunity.

And for the second time in less than two months, Perdue’s timing was impeccable. He avoided a sharp loss and reaped a stunning gain by selling and then buying the same stock: Cardlytics, an Atlanta-based financial technology company on whose board of directors he once served.

On Jan. 23, as word spread through Congress that the coronavirus posed a major economic and public health threat, Perdue sold off $1 million to $5 million in Cardlytics stock at $86 a share before it plunged, according to congressional disclosures.

Weeks later, in March, after the company’s stock plunged further following an unexpected leadership shakeup and lower-than-forecast earnings, Perdue bought the stock back for $30 a share, investing between $200,000 and $500,000.

Those shares have now quadrupled in value, closing at $121 a share on Tuesday.

The Cardlytics transactions were just a slice of a large number of investment decisions made in the early days of the pandemic by Perdue and other senators. They stirred public outrage after it became clear that some members of Congress had been briefed on the economic and health threat the virus posed. The transactions were mentioned briefly in a story published by the Intercept in May.

Now that Perdue is locked in a pitched battle for reelection in a Jan. 5 runoff, his trades during a public health and economic crisis have become an issue in what already has become a negative, expensive campaign that will determine which party controls the Senate.

There is no evidence that Perdue, who is among the wealthier members of the Senate, acted on information gained as a member of Congress or through his long-standing relationship with company officials. It’s illegal to use nonpublic information gained as a company insider or member of Congress to make investment decisions.

But legal experts say the timing of his sale, the fact that he quickly bought Cardlytics stock back when it had lost two-thirds of its market value and his close ties to company officials all warrant scrutiny.

“This does seem suspicious,” said John C. Coffee Jr., a Columbia University law school professor who specializes in corporate and securities issues. But he added, “You need more than suspicions to convict.”

The Perdue campaign declined a request for an interview with the senator. In a statement, Perdue spokesperson John Burke said the senator had been cleared of wrongdoing but did not provide details.

“The bi-partisan Senate Ethics Committee, DOJ and SEC all independently and swiftly cleared Senator Perdue months ago, which was reported on,” Burke said.

Perdue’s opponent, Democrat Jon Ossoff, has seized on his stock trading while trying to brand him as a “crook.”

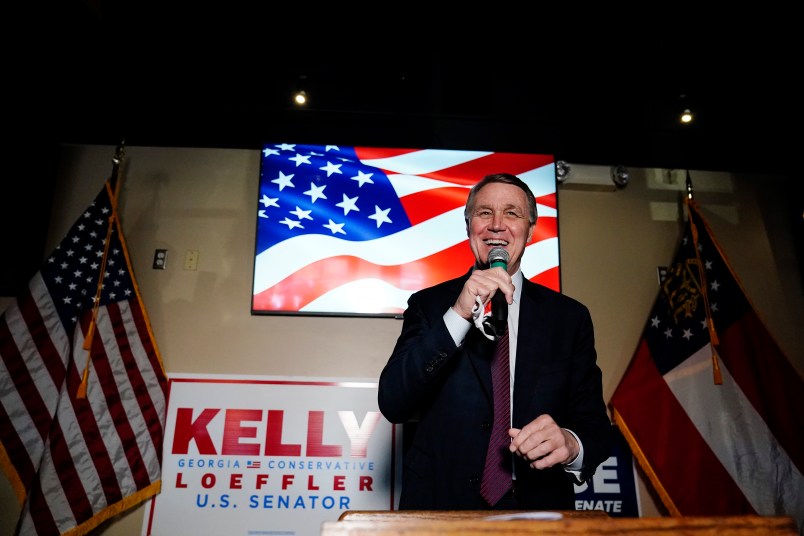

Perdue is not the only senator on the ballot in Georgia. Sen. Kelly Loeffler, also a Republican, is running against Democrat Raphael Warnock in a bid to complete the remainder of retired Sen. Johnny Isakson’s term.

Perdue’s Cardlytics transactions fit into a broader pattern of stock moves he made when the coronavirus first struck the U.S.

At the time, Perdue publicly maintained that the economy was strong and praised President Donald Trump during a Feb. 24 interview on Fox News Channel for “executing the greatest economic turnaround in U.S. history.”

A series of swift transactions in his portfolio told a different story, however, showing the senator dumped some company stocks, while investing in others — like protective equipment maker DuPont and pharmaceutical company Pfizer — that were poised to do well during the pandemic.

Perdue has previously said that outside financial advisers make most of his trades.

But Donna Nagy, an Indiana University law professor, said that type of arrangement doesn’t preclude Perdue from directing an adviser to make specific transactions. She said one way for members of Congress to avoid questions about their financial holdings is to put them in a blind trust, which Perdue has not done.

“All of these questions about the motivations behind our members of Congress and their personal securities trading could be alleviated if Congress passed a law that limited investments,” said Nagy, who specializes in securities law. “Ordinary citizens should not have to question members of Congress about their investments.”

The issue was enough of a liability that Perdue abruptly sold off between $3.2 million and $9.4 million of his stock portfolio over a four-day period in mid-April, according to an Associated Press review of mandatory financial disclosures he has submitted to the Senate. He did not sell his stock in Cardlytics.

Still, Perdue has largely avoided the same degree of scrutiny faced by some of his colleagues.

Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina drew the most attention and stepped down as Senate Intelligence Committee chair amid a probe of his sale of upward of $1.7 million in stock, which came when he was privately warning some well-heeled constituents about the virus while publicly downplaying the threat.

Cardlytics works at the intersection of banking and online marketing. It helps run rewards programs for financial institutions, including Wells Fargo, using data the banks have gathered on their customers to market to them — similar to what Facebook does with targeted ads.

The company did not respond to a request for comment.

After the March turmoil, its share price dramatically rebounded. Lynne Laube, Cardlytics’ current CEO, said the pandemic had a lot to do with it, driving consumer interest in savings programs.

“I hate to say this pandemic is playing in our favor, but it’s playing in our favor,” she said during an earnings call in May.

Perdue acquired 75,000 shares in Cardlytics through stock options offered for his service on the company’s board from 2010 to 2014, when he stepped down after winning his Senate seat, Securities and Exchange Commission filings show. The company, which at the time had not yet gone public, also offered him options that would become available in October 2020 and January 2022.

Perdue’s latest financial disclosures do not indicate whether he has exercised the options that became available in October.

But according to Coffee, the Columbia University law professor, it’s an unusual move by the company.

“I’ve never seen options extended from 2014 to 2022,” he said. “That’s a very long extension.”

While Perdue left the company’s board, he has maintained ties to some of its executives, who have donated more than $30,000 to his political committees. Donations made to Perdue account for nearly 80% of all giving to federal candidates by Cardlytics employees over the past decade, records show.

Perdue, meanwhile, has used social media to publicize the company. In August 2016, he took a tour of its office and posed for a photo with Laube and then-CEO Scott Grimes, which he posted to Facebook. In fall 2019, he introduced Laube and Grimes at a gala in Atlanta, where they received a business achievement award.

Isakson, who served with Perdue, took steps to avoid the type of scrutiny Perdue is now facing. Isakson, a Republican, put most of his own holdings in a blind trust after some of his assets drew unwanted attention in 2012.

“I said I need to be as patently pure and patently clean as anybody, and the best way to do that is a blind trust,” Isakson, who served on the Senate’s finance and ethics committees, told the Atlanta Journal Constitution in 2017. “I don’t know what I own.”