The Supreme Court heard arguments Wednesday in which North Carolina Republicans pushed the independent state legislature theory, the idea that only state legislatures, to the exclusion of organs including state courts and constitutions, are allowed to control federal elections.

The theory would imbue state legislatures with towering power to gerrymander, pass voting restrictions and administer elections without any of the checks and balances that have historically constrained their authority.

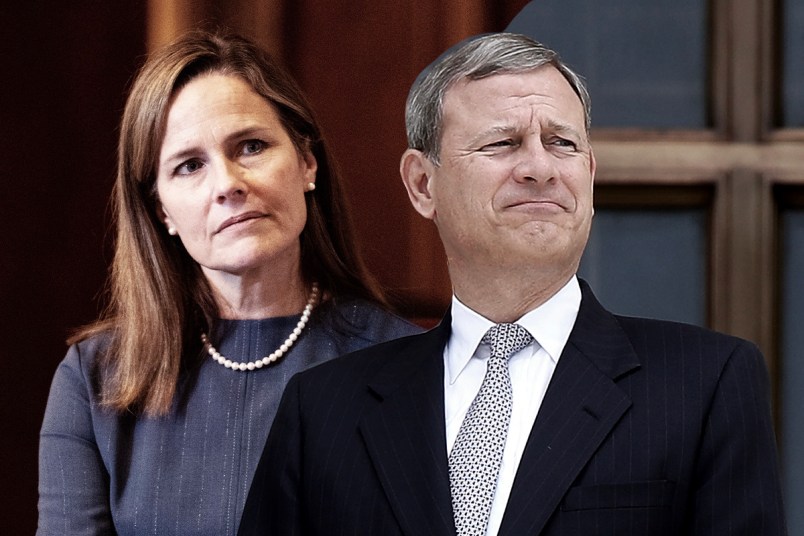

Coming into the arguments, we had a fairly good sense of where most of the justices land on the theory. The three liberals, predictably, oppose it. Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch eagerly embrace it. Justice Brett Kavanaugh is, at the very least, ISLT-curious and perhaps amenable. Chief Justice John Roberts has been all over the place, but most recently landed in a place of at least some opposition. And Justice Amy Coney Barrett is a complete mystery.

On Wednesday, Kavanaugh, Roberts and Barrett — two of the three who would likely have to side with the liberals to thwart the ISLT — each at times expressed dubiousness about various parts of North Carolina’s argument.

A big sticking point was North Carolina’s odd attempt to split the baby. The state legislators maintain that it’s just the state legislatures and only the state legislatures that get to control federal elections in their states…except for the gubernatorial veto, which is somehow allowed while other checks, such as state courts and state constitutions, are not.

“That’s a pretty significant exception,” Roberts said to North Carolina’s attorney. “You have otherwise a very categorical case — and it’s sort of, well, with this one exception. Vesting the power to veto the actions of the legislature significantly undermines the argument that it can do whatever it wants.”

Barrett quickly jumped onto the Chief’s point, asking if the state’s arbitrary division of the veto from other checks is “just a way of trying to deal with our precedent.”

“Because you do have a problem with explaining why these procedural limitations are okay, but substantive limitations are not,” she added.

Kavanaugh, in a big moment, suggested that the state is going further than a concurrence written by former Chief Justice William Rehnquist in Bush v. Gore that provided an early articulation of the independent state legislature theory. It was an important tea leaf from Kavanaugh, since he once wrote:

“As Chief Justice Rehnquist persuasively explained in Bush v. Gore … the text of the Constitution requires federal courts to ensure that state courts do not rewrite state election laws.”

Kavanaugh paraphrased Rehnquist’s position that state courts should have a role interpreting state law, and that federal review should be very deferential to the states’ interpretations, only coming into play if the state court significantly departs from the state law.

If that’s where Kavanaugh stands too, and if he is uncomfortable with going beyond that idea, it would, at the very least, stop the majority from rubber stamping a maximal interpretation of the ISLT which cuts state courts out of the equation altogether.

The question of when federal courts would get to swoop in and review state court decisions bedeviled the justices from both ideological sides throughout the arguments. In general, the right-wing justices worried that the standard would be too high, elbowing out the federal judiciary completely. Kagan voiced her concern that the standard would be too low, setting up a situation that U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar described as the federal courts being flooded with election litigation as unsuccessful parties from state court try to get a “second bite at the apple.”

Kavanaugh and Barrett poked at other angles of North Carolina’s arguments too.

Kavanaugh, citing a brief from the conference of chief justices that opposed the ISLT, pointed out that “nearly all state constitutions regulate federal elections in some way.”

Under the ISLT, all of those passages in state constitutions would be null and void.

Barrett, separately, offered up the hypothetical of a state constitution being amended by ballot referendum, saying that the Court’s precedent suggested that the referendum mechanism for redistricting does not violate the Elections Clause. Why then, she asked, since the referendum method is okay in the Court’s lights, would that part of the state constitution suddenly be nixed by the ISLT?

It’s not uncommon for Barrett and Kavanaugh in particular to sound sympathetic to both sides during cases like these — they tend to be less crusading in their approach than, say, Alito, who generally leaves little question as to where he stands. There’s always the possibility that, despite reservations from these two and Roberts, the majority will end up greenlighting a theory that could upend free and fair elections by a 6-3 margin.

But if North Carolina, and the right-wing forces that have been pushing to get this theory into the Court’s bloodstream for a while, were hoping for six voices raised unanimously in full-throated support of the ISLT, they’ll likely be disappointed.