What’s all this talk about a “second wave” of U.S. coronavirus cases?

In The Wall Street Journal last week, Vice President Mike Pence wrote in a piece headlined “There Isn’t a Coronavirus ‘Second Wave'” that the nation is winning the fight against the virus.

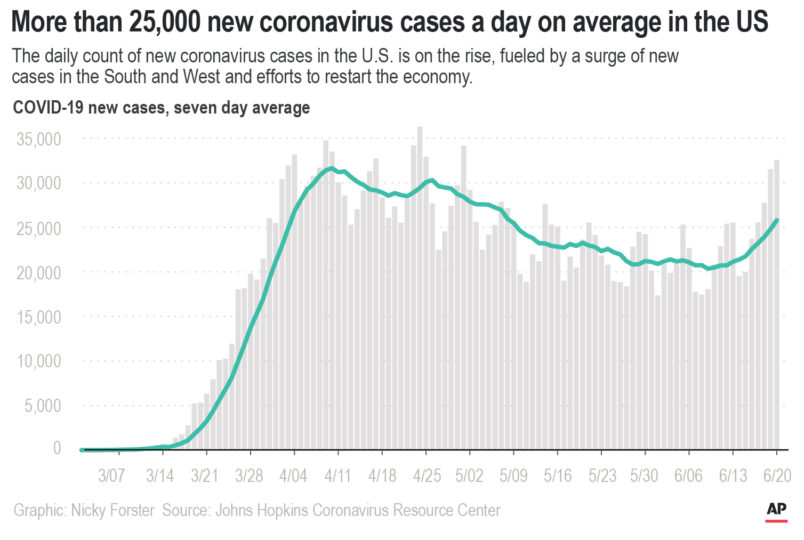

Many public health experts, however, suggest it’s no time to celebrate. About 120,000 Americans have died from the new virus and daily counts of new cases in the U.S. are the highest they’ve been in more than a month, driven by alarming recent increases in the South and West.

But there is at least one point of agreement: “Second wave” is probably the wrong term to describe what’s happening.

“When you have 20,000-plus infections per day, how can you talk about a second wave?” said Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health. “We’re in the first wave. Let’s get out of the first wave before you have a second wave.”

Clearly there was an initial infection peak in April as cases exploded in New York City. After schools and businesses were closed across the country, the rate of new cases dropped somewhat.

But “it’s more of a plateau, or a mesa,” not the trough after a wave, said Caitlin Rivers, a disease researcher at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security.

Scientists generally agree the nation is still in its first wave of coronavirus infections, albeit one that’s dipping in some parts of the country while rising in others.

“This virus is spreading around the United States and hitting different places with different intensity at different times,” said Dr. Richard Besser, chief executive of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation who was acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when a pandemic flu hit the U.S. in 2009.

Dr. Arnold Monto, a University of Michigan flu expert, echoed that sentiment.

“What I would call this is continued transmission with flare-ups,” he said.

Flu seasons sometimes feature a second wave of infections. But in those cases, the second wave is a distinct new surge in cases from a strain of flu that is different than the strain that caused earlier illnesses.

That’s not the case in the coronavirus epidemic.

Monto doesn’t think “second wave” really describes what’s happening now, calling it “totally semantics.”

“Second waves are basically in the eye of the beholder,” he said.

But Besser said semantics matter, because saying a first wave has passed may give people a false sense that the worst is over.

Some worry a large wave of coronavirus might occur this fall or winter — after schools reopen, the weather turns colder and less humid, and people huddle inside more. That would follow seasonal patterns seen with flu and other respiratory viruses. And such a fall wave could be very bad, given that there’s no vaccine or experts think most Americans haven’t had the virus.

But the new coronavirus so far has been spreading more episodically and sporadically than flu, and it may not follow the same playbook.

“It’s very difficult to make a prediction,” Rivers said. “We don’t know the degree to which this virus is seasonal, if at all.”

___

AP medical writer Lauran Neergaard contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.