Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for the majority, slapped down New York’s 100-year-old concealed carry licensing scheme Thursday on the grounds that it has no historical analogue.

Government interest — like protecting the safety of its citizens — is not enough to get around the all-expansive Second Amendment, he writes. To be legitimate, a gun regulation must have a historical cousin.

The notion is farcical on its face: there must be some 18th or 19th century law mirroring any modern-day gun regulation, even for weapons that the people of that time could not have imagined existing?

It rings similar to Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion overturning abortion rights, which roots much of its argument in cases where abortion access was not protected in the country’s earliest days, and before. He asks readers to unflinchingly accept that a constitutional right for women is only valid if it existed in a time when women were considered much less than full citizens.

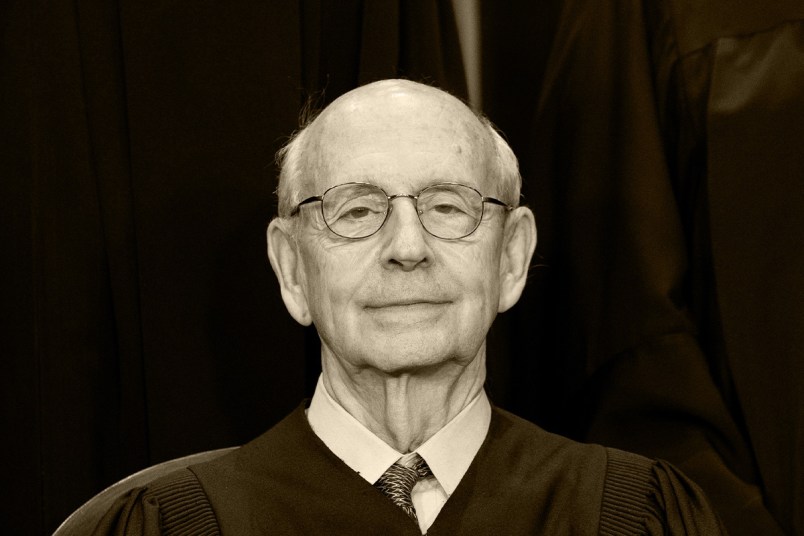

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, focuses his dissent on the patent ludicrousness of determining constitutional rights solely through historical precedents.

“Will the Court’s approach permit judges to reach the outcomes they prefer and then cloak those outcomes in the language of history?” he ponders, before sketching out his argument that his conservative colleagues have done just that.

Breyer lays out his own list of cases ranging from English precursors to early American laws all the way up through U.S. law in the 20th century. He lists cases that he argues support New York’s licensing scheme, many of which the conservative majority found some reason to reject: “too old,” “too recent,” “did not last long enough,” “applied to too few people,” “enacted for the wrong reasons,” “based on a constitutional rationale that is now impossible to identify,” “not sufficiently analogous,” Breyer reels off.

“At best, the numerous justifications that the Court finds for rejecting historical evidence give judges ample tools to pick their friends out of history’s crowd,” he writes. “At worst, they create a one-way ratchet that will disqualify virtually any ‘representative historical analogue’ and make it nearly impossible to sustain common-sense regulations necessary to our Nation’s safety and security.”

Besides the easy ability for judges to cherry-pick historical cases that help their argument and dismiss those that don’t, Breyer points out the practical implications of such an approach to law.

Judges, and their staff, he points out, are trained in law, not in history.

“Lower courts — especially district courts — typically have fewer research resources, less assistance from amici historians, and higher caseloads than we do,” he points out. “They are therefore ill equipped to conduct the type of searching historical surveys that the Court’s approach requires.”

He adds that the Supreme Court has been wrong before when it’s tried to base decisions on historical laws. He points to scholarship debunking the basis of District of Columbia v. Heller, the most recent major Supreme Court gun case, where the majority found that the Second Amendment covered the right of individuals to bear arms for self defense, such as keeping a handgun in the home for protection.

“The Court’s past experience with historical analysis should serve as a warning against relying exclusively, or nearly exclusively, on this mode of analysis in the future,” he writes.

The ramifications of this case, and this seeming trend of the Court’s, could be dire. Even Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s insistence that this decision applies only to licensing laws like New York’s and not the more lenient ones in the majority of states rings hollow. If they buy Thomas’ approach to historical analysis, how can that be true? And how can readers trust those assertions, given that the conservative majority is surely more than able to find some smattering of historical cases that undermine those specific permitting schemes too?

Again, it brings Alito to mind. In his draft decision overturning Roe v. Wade, he pauses many times to assure readers that this decision will have no bearing on other privacy right-based protections, like gay marriage. He then goes on to make an almost completely historically based argument, relying on such pillars as the word “abortion” being absent from the Constitution, and the lack of abortion rights in colonial days. How can anyone believe that same-sex or interracial marriage are safe within that framework?

At points, Breyer can’t help but verbally throw up his hands at what his conservative peers are asserting.

“How can we expect laws and cases that are over a century old to dictate the legality of regulations targeting ‘ghost guns’ constructed with the aid of a three-dimensional printer?” he asks incredulously.