Many of the controversial full-body airport security scanners that generated images of passengers described as “naked,” or “nearly naked” by critics and the press, will be removed from U.S. airports as of June, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) announced on Friday, ending a $5 million contract.

But the approximately 250 scanners that the TSA has pledged to remove won’t go unused for long: The TSA has entered into an agreement with Rapiscan Systems, the company that makes them, to redeploy the devices “to other mission priorities within the government,” as the TSA put it in an official blog post.

“We are working with the TSA to send them to other government agencies that already use the technology,” said Peter Kant, executive vice president at Rapiscan, in a phone interview with TPM. Rapiscan is a subsidiary of OSI Systems.

Kant declined to specify exactly which agencies would be receiving the scanners and how many, but told TPM that the devices would be used by “military and law enforcement, for the most part.”

“We have a long history of working with the TSA and we support the move of these technologies,” Kant said.

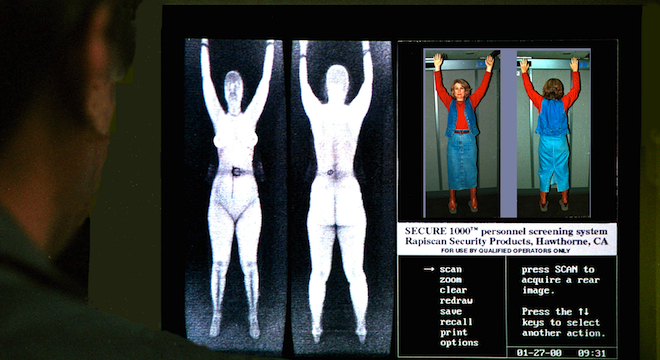

Rapiscan’s scanners in question are specifically known as the “Secure 1000SP,” (Secure 1000 “single pose”) and were originally deployed in airports across the country in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. The Secure 1000SP scanners rely on a technology called backscatter, which involves beaming low dose X-rays against a passenger’s entire body — Rapiscan says on its website it uses a “narrow pencil tip sized beam — and then collecting and analyzing the resulting photons that bounce back off the person’s body. From this, security officers can pinpoint whether the passenger is carrying prohibited items, including non-metal explosives, which would not be picked up by a standard metal detector.

“There’s no other effective way to detect explosives aside from hand scanning, which is even more invasive,” Kant explained. “That’s why we went and developed this technology. It’s the most widely used non-metal scanning detector in the world.”

The technology, specifically Rapiscan’s implementation of it in airport scanners, has been called into question over potential negative health effects. European Union regulators in late 2011 moved to prohibit any type of X-ray scanner in airports pending further testing. But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2010 released a statement saying that X-ray security scanners presented “no more than a miniscule risk to people being scanned.” (The TSA also rebutted health concerns in 2009).

It was privacy concerns, though, over the highly-detailed images of passengers’ bodies under their clothes, that finally led to the dissolution of Rapiscan’s contract with the TSA.

In early 2012, Congress passed a Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization bill (PDF) that mandated all body scanning machines include software that renders a passenger’s body scan anonymized, replacing their body with a generic character avatar with markings showing the location of any suspicious materials (screenshot below, via the TSA blog):

That software, called “automated target recognition (ATR),” was due to be in place on all backscatter full-body scanners, including Rapiscan’s, by June 2013.

But the company told the TSA that after much testing, it could not meet the deadline in time to implement the software on its Secure 1000SP scanners, leading the TSA to pull the plug on their use in airports and yank a $5 million contract to add the new software.

“We were trying to retrofit our scanners with this technology after they had already been deployed,” Kant told TPM. “What we did was we went to the TSA and told them, before they spent the money, was that we would not be able to get the technology installed by that deadline. We said, ‘what would you like to do?’ They said there is still plenty of use for the technology and there are a number of other U.S. government agencie that could benefit from and use it.”

The TSA will be replacing the roughly 250 individual Rapiscan Secure 1000SP scanners it is removing from airports with another type of technology, millimeter wave, which does not use X-rays, but rather, radio waves, and which has not drawn nearly as many health questions or privacy concerns.

TPM has reached out to the TSA for more information on the the full-body scanner redeployment plans and will update when we receive a response.

Rapiscan will not be upgrading the removed scanners with any new anonymizing technology prior to redeployment, Kant told TPM. The company will eat a $2.7 million charge to remove and redeploy the scanners, but will presumably sign new contracts with any agencies that use them instead of the TSA.

Still, despite the setback, the company overall is not hurting as a result of the canceled TSA contract, as Kant told TPM.

“Of course we’re disappointed we weren’t able to meet the TSA’s timeline,” Kant said. “But this is an extremely minimal amount of our overall business.”

Rapiscan is the largest security scanner company in the U.S. and “one of the largest in the world,” Kant told TPM. It counts over 100,000 scanning machines in 130 countries, including 1,800 other X-ray systems that the TSA uses for baggage and cargo scanning. Rapiscan also makes millimeter wave machines like that kind that will be replacing its backscatters in airports, but Rapiscan’s aren’t designed for use in that environment and are instead used “primarily for theft prevention” at large distribution warehouse centers used by some of the world’s leading tech companies. Rapsican’s Kant declined to specify which specific electronics companies use its scanners to safeguard their product inventories.