Just in time for an extremely variable winter storm forecast for the Northeast this weekend, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on Wednesday announced a new smartphone app that lets users report on winter precipitation in the area and view a map of the U.S. showing all the reports made by fellow users across the country.

The app is called “mPING” (short for mobile Precipitation Identification Near the Ground project) and is available for free for Apple’s iPhone and devices running Google’s Android software.

Users are given a choice to select between 12 different precipitation categories — including everything from rain to snow to hail to ice pellets/sleet, plus “none” and “test” options. Here’s a screenshot of some of the mPING app’s interfaces:

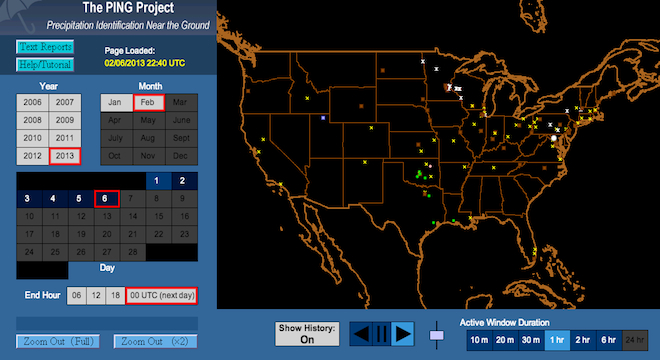

A user simply presses the option that he or she observes in front of them, then clicks “submit report,” and the app automatically sends the precipitation type, the time, and the user’s location down to within a radius of 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) to map showing all the other reports in realtime. Check out an animated GIF of the map below:

The map is accessible both within the mPING app and live on the Web, where desktop computer users can also submit their own reports (though Web users have to their provide latitude and longitude coordinates, which the smartphone app automatically obtains.)

The collection of all the realtime precipitation reports could be a tremendous help in preparing for sudden and severe winter weather, especially for local governments and utilities companies.

“It helps us begin to identify what’s going on,” said Kim Elmore, a PhD meteorologist and research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, a partnership between NOAA and the University of Oklahoma, which is responsible for the data. “Is this weather doing what forecasters expected? So if, for example, it starts snowing earlier than anybody expected, accumulation will probably be greater than expected as well.”

Elmore pointed out that such information would prove immediately instrumental to those in government and industry that are responsible for dealing with or working around severe weather conditions.

“If you’re working for a power company and all of the sudden you start to see reports of freezing drizzle that weren’t forecast, you might think, ‘OK, we’re not in trouble now, but we could be in the next few hours. Let’s get crews in place in case any power line get knocked down,'” Elmore explained. “If you’re a city manager, you can begin to get salt trucks and plows ready to go as soon as you see reports of snow or freezing drizzle. If you’re a forecaster and the reports disagree with your forecast, you can update it, so the uncertainty is minimized.”

Of course, because the app is free, anyone is welcome to download and use it to submit or view reports — not just those who have an immediate responsibility for dealing with adverse weather conditions. In fact, NOAA is actively encouraging casual users to download the app and submit reports of conditions in their area to help improve its models and stay informed.

“The ability to have this data displayed and to be able to make sense of it is useful to anyone,” Elmore said. “I’ve had people come over and tell me, ‘This is nuts, I have to turn off my web browser'” because the live map of precipitation reports is so addictive, Elmore said.

From the desktop PING website, users can also download full text archives of all the reports that other users have submitted going back to 2006, when NOAA first launched the ability for users to report precipitation via simple web forms.

NOAA’s underlying goal in making the app and the PING website is in helping to improve a new weather tracking algorithm that Elmore developed, also back in 2006. Called the “winter surface hydrometeor classification algorithm,” or “WSHCA” (pronounced “Wish-ka”) for short, the algorithm uses the crowdsourced data along with data collected by National Weather Service radar installations across the country to more accurately determine realtime weather conditions on the ground in all areas.

Elmore’s new WSHCA algorithm was itself the result of the realization that an older algorithm designed to measure rainfall rates wasn’t able to accurately describe snowfall rates or other winter weather conditions.

Indeed, when it comes to winter weather in particular, human beings are still the best judge of the type of precipitation.

“We do have automated systems, but they don’t report mixes well,” Elmore told TPM. “Rain mixed with snow, ice pellets mixed with rain; they have trouble with drizzle, too.”

That’s why NOAA launched the PING project in 2006. But the Web form was restrictive and didn’t see enough participation for researchers to effectively use the data in the algorithm until 2012, when the agency implemented yet another stepping stone solution to the mPING app — phone banks staffed with paid college students, who cold called people and asked them to verbally describe participation occurrences. By the end of 2012, NOAA had collected 4,000 reports, enough to start its analysis.

Around the same time and in the months before, someone at NOAA — Elmore can’t remember who, exactly — said a smartphone app would be a superior method of soliciting crowdsourced weather reporting data. Yet it wasn’t until Elmore mentioned the idea to a friend of his, Zac Flamig, from amateur radio club, that it moved into action. Flaming was an iOS app developer on the side, and he quickly created the app that would become mPING.

The iPhone version of mPING was first soft-launched in mid-December 2012 and the Android version several days later, but NOAA didn’t publicize it until now because it wanted to work out all the initial release bugs, Elmore told TPM.

All of it was “essentially developed for free” thanks to Flamig’s quick work and generosity with the app, Elmore told TPM.

As of last week, despite the lack of publicity, mPING had over 8,000 users, Elmore said, predicting it had already crossed 10,000 before NOAA began publicizing it.

“We suspect the vast majority of people using it up until now had a particular interest in weather,” Elmore said. “But everyone is interested in the weather to some degree.”