If you’re queasy about getting shots because you don’t like needles, MIT scientists have developed a new drug injection method just for you.

Instead of pricking the skin, a prototype handheld injector device instead delivers medicine as an extremely thin, exceptionally high-powered jet of liquid, which has enough force to breach skin, yet does so with such precision and speed that it doesn’t cause pain or discomfort, nor does it leave behind a noticeable hole, according to the MIT researchers who created it.

“Skin is flexible and because the hole we produce is so small the elasticity of the skin ‘closes up’ the hole,” said Ian Hunter, an MIT professor of mechanical engineering that led the research behind the prototype injector, in an email to TPM.

“Moreover, the skin repairs the hole in a day or so,” he added.

In a video demonstration of the new injection method and prototype device posted online Thursday, Hunter compared the sensation of getting the drugs injected via a jet to getting bitten by a mosquito — barely noticeable for most people.

To be fair, though, Hunter and his colleagues haven’t yet begun human trials of their new prototype device. So far they’ve just tested it on gel, animal tissues and several living animal subjects, including sheep.

“In sheep it appeared that the sheep was not even aware that it was being injected,” Hunter told TPM. “Human testing is a high priority and should start in the near future.”

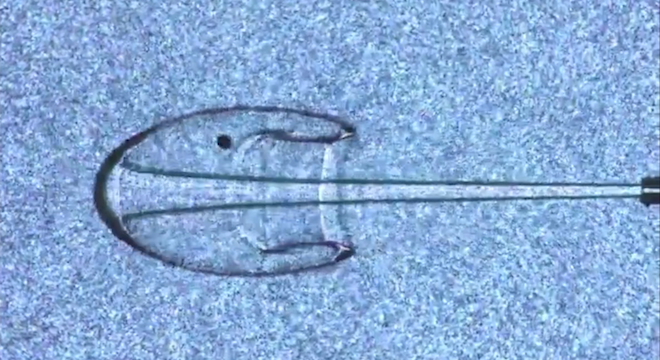

The method developed by Hunter and his colleagues relies on a device called a Lorentz force actuator. This consists of a strong magnet and an electrode, in this case, copper wire coiled around the magnet, attached to a piston. When a current is sent through the wire, it interacts with the magnetic field, causing the piston to fire and expel the liquid at an incredible velocity.

Illustration showing the inner-workings of MIT’s new liquid jet injector, courtesy MIT BioInstrumentation Lab.

“We find that its is a combination of both force (or pressure) and velocity of the jet which determines the effectiveness of the penetration and the depth of the delivery,” Hunter told TPM. “Our pressures are typically at least 50 times atmospheric pressure and our velocities are typically well over 1/10th the speed of sound (in air) and sometimes as high as the speed of sound.”

In fact, the prototype device works so well that it has even been able inject solids — in the form of powder and tiny beads — into nonhuman test subjects in laboratory trials. What happens is that the powder and beads are shot at such high velocity, they take on the properties of liquids. As Hunter noted in an MIT news article, this could be helpful in cases where some drugs can only be stored for long periods of times as powder, with the liquid forms requiring refrigeration.

Hunter said he has his colleagues at MIT built their prototype device in six months.

“We now build every thing from scratch,” Hunter told TPM. “Much of the scientific apparatus required to measure and quantify the injections did not exist so we had to design and build these.”

The injector can be used for everything from small doses of insulin required by diabetics to larger doses of other drugs, including liquids as viscous as honey.

The team was able to overcome physical volume limitations of storing enough medicine in one actual handheld device itself by building a prototype with two Lorentz force actuators. As the first actuator is running out of liquid, the second is hooked up to a reservoir of medicine and then “takes over” the role of the first actuator, pumping drugs through the tiny hole. While that one is injecting the medicine, the first actuator is drawing upon the reservoir of medicine, and so on.

“We can produce an almost continuous flow and can deliver large volumes (or equivalently for use during emergences where a very large number of people must be inoculated or for use on farms where a large number of animals must be inoculated),” Hunter told TPM.

As for the cost compared to the plain old needles, Hunter acknowledged that was still one area were more work was being done.

“We are trying our best to keep the costs low,” Hunter wrote. “A needle and plastic syringe is a very low cost combination. But when you step back and consider the human cost of needle-stick injuries and other misuse of needles and syringes we feel that our technology becomes cost effective.”

Hunter and several colleagues from other universities first laid out the groundwork for the new method in a paper in 2006. Their successful prototype injector is explained in a new paper published online in the journal Medical Engineering & Physics.