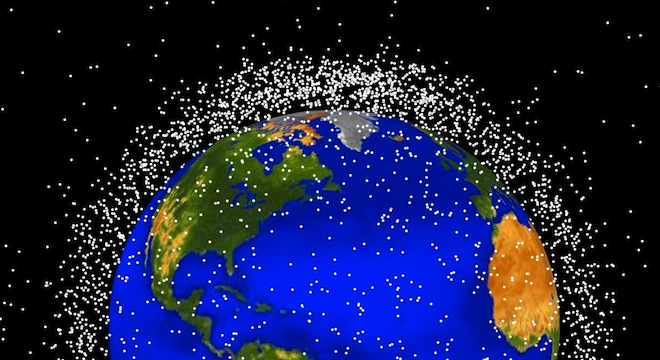

In order to clean the area of space just outside Earth, scientists may have to make it a whole lot messier first.

The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory recently announced a bold, almost counterintuitive plan to bring down the hundreds of thousands of pieces of space junk currently orbiting the Earth — made up of dead satellites, leftover equipment, and tiny meteorites — by launching rockets carrying clouds of dust particles into orbit.

A certain amount of metallic dust — enough to cover 18 to 31 miles — released in a strategic polar orbit, would produce increased drag on the the space junk and cause it to fall back into Earth’s atmosphere, where it would harmlessly burn-up, according to the scientists who devised the plan.

The dust, too, would eventually plummet toward the planet and burn up, but the entire process could take 10 to 25 years for all of the debris and dust to be destroyed.

“In principle, all the small untrackable debris may be targeted and removed,” said Gurudas Ganguli, the NRL space scientist who led the team that devised the method, in an email to TPM. “But cost/benefit analysis will have to be performed to decide what fraction of the debris needs to be removed in order to make the remaining risk acceptable.”

Indeed, in two scientific papers provided to TPM, Ganguli and his researchers acknowledge the risks that would accompany such an unorthodox method of space junk removal, including potential damage to operational satellites and spacecraft also in orbit.

“Some fraction of the dust may escape the layer and disperse in space,” one paper notes, “Solar arrays could also be degraded by dust impacts, but that effect can be mitigated by thicker cover glass.”

The researchers also propose having at-risk spacecraft be moved out of the way of the cloud before it is dispersed.

“No dust will be left on orbit permanently,” Ganguli pointed out to TPM.

Ganguli’s team is so optimistic that the their dust-to-dust method is workable that they have already filed a patent for it. Ganguli also told TPM it could be begun quickly using today’s technology, with the dust clouds being launched in “4 to 5 years after some more research and ground testing,” as he put in an email.

As for the actual cost of the method, Ganguli and his colleagues haven’t put a number one it, but they point out that it would almost certainly be much less and drastically more effective at removing orbital debris than other currently proposed methods, such as a Swiss plan to launch “janitor satellites” to individually pick up pieces of space junk and de-orbit them, or a Pentagon research plan to actually re-animate select pieces of dead spacecraft, turning them into radio transmitters.

Further, the plan could target individual pieces of space junk and release smaller clouds of dust as well.

“No exotic technology, station keeping, or on-orbit maintenance, are required, Ganguli noted to TPM. “It is a low-tech approach exploiting gravity and utilizing the natural orbit decay process by artificially and temporarily enhancing it.”

Still, whether or not NRL’s plan actually gets put into effect, it’s becoming increasingly urgent for space scientists, or someone, to address the escalating amount of orbital debris. A 2011 research report found that the level of debris in orbit may have actually reached a “tipping point” and could soon lead to the Kessler effect, a theory named for the scientist who first proposed it back in the 1970s, which states that space could eventually become too dangerous too venture into if space junk got so dense it produced a series of cascading, virtually endless series of collisions.

Two years before that report, in 2009, an American telecommunications satellite collided with a Russian one, destroying both and sending debris flying toward the International Space Station. Although no subsequent damage ensued, spacefaring nations hope to avoid a repeat of such an event.