NASA’s Mars Curiosity Rover isn’t done blasting the Red Planet with a rock-vaporizing laser. In fact, its work has barely begun.

On Saturday, October 20, as the rover picked up its fourth scoop of Martian soil and prepared it for analysis, it also fired its separate Chemistry and Camera instrument (ChemCam) at a target dubbed “Crestaurum,” hitting it with over 30 laser shots and leaving behind a hole 3 millimeters wide.

The laser shots were fired from nearly nine feet away and were issued from the ChemCam instrument mounted on the rover’s 3.6-foot tall mast.

NASA announced the operation in a news release posted Monday on its Jet Propulsion Laboratory website (JPL is in charge of the rover’s operations).

Check out the resulting “before and after” GIF posted by NASA, clearly showing the hole being burned into the sample area of sand by the invisible laser beam.

“The Crestaurum target was selected to study whether frost accumulates on Mars’ surface at night,” said ChemCam Principal Investigator Roger Wiens of Los Alamos National Laboratory in a statement emailed to TPM. “The idea was to take one measurement of Crestaurum at night and one during the day for comparison.”

It’s clear that frost accumulates in some regions of Mars based on prior analysis work by the stationary NASA Mars Phoenix Lander in 2008. NASA in September 2012 also announced that it had found evidence that it snows dry ice (carbon dioxide crystals) on the south pole of Mars based on imagery taken by the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter satellite.

However, NASA hasn’t yet completed its analysis work on the new target Crestaurum.

“The day-time measurement was made before sundown, and we received the data back almost right away,” Wiens said. “We are still waiting for the night-time results, which are in the downlink queue, but are taking a little longer, so we don’t yet have the results of the frost study.”

It’s early Spring on Mars where the rover is located, just four degrees shy of the Martian equator, and temperatures are getting warmer, so the study needed to be carried out now, according Wiens.

ChemCam is a military-grade laser and an associated micro-imager that zaps sample areas smaller than 1 millimeter to clear away dust and allows the camera to focus on them with greater detail than any imager ever sent to Mars previously. The laser is also capable of vaporizing rock and soil samples and analyzing the composition of the plasma cloud left in the wake, allowing Curiosity’s scientists to determine exactly the chemical and mineralogical composition of sample targets.

Meanwhile, NASA is also still assessing the composition of unexpectedly shiny particles found strewn among the more bland, darker colored reddish and gray soil at the rover’s current site, an area known as Rocknest.

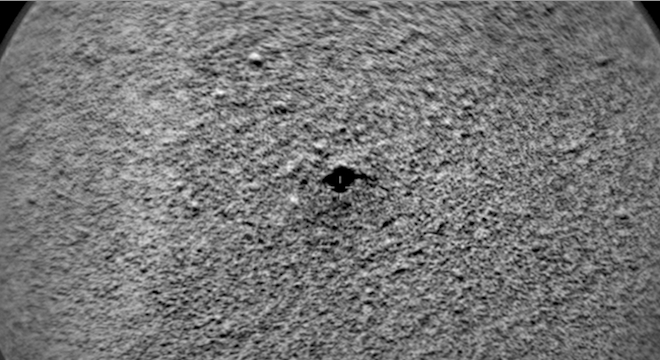

Here’s a close-up image of one of those shiny particles taken by Curiosity’s Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), a geology camera located on the end, or “hand,” of the rover’s 7-foot-long robotic arm:

The shiny particles, first spotted after the Curiosity rover’s second scoopful of Martian sand and imaged on October 15, appear to be native to Mars, as opposed to an earlier surprising shiny object that turned out to be plastic wrapper that fell off the wiring of the rover’s discarded descent stage.

However, a NASA spokesman told TPM that the rover’s main activity at the site was still scooping and running soil samples through its Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument and the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument. Counterintuitively, the rover’s first three scoopfuls of Martian sand were actually used to clean some of its instruments, “scrubbing” them free of an oily film that is unavoidable due to the rover originating on Earth, despite the fact that it was assembled in a hyper-controlled sterile environment at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

The Curiosity rover, which is on the third month of a 23-month-long scientific mission, is expected to remain at Rocknest for several more days before driving to a new site of diverse Martian geology known as Glenelg. It’s ultimate goal is a 3.4-mile high Martian mountain known as Mount Sharp.